A Crude Guess About The Future

Though it has an upside for the biosphere that shouldn’t be ignored, $100/barrel oil definitely isn’t much fun for our pocketbooks or the world economy. And could worse times be ahead?

When we see spikes like this, there are inevitably voices predicting stratospheric prices for crude just beyond the horizon. The basic reasoning is that oil supplies are finite (clearly, in the very big picture they are), and that world oil demand is set to skyrocket thanks in large part to the motorization of India and China (it is—see my last post.) “Peak oil” advocates maintain that at some point we are simply bound to run out of the stuff.

I’ve never been a big fan of the peak oil story. First, price signals will encourage conservation as oil gets more dear, reducing demand pressure. We’ve already come a long way on that front; in 1970, the average car on the road got about 14 mpg, and the average van, light truck or SUV about 10. Today, the averages for new cars and trucks sold are considerably more than double those figures, and things continue to move in the right direction thanks to government regulation (rising CAFE mpg standards), new technology (including but not limited to hybrids), and the fact that consumers respond to oil price increases pretty much like economists predict they should, changing purchasing, travel and location decisions in order to conserve when oil prices rise.

Much more dramatic than anything on the demand side, though, has been our stunning record at increasing supply, which has been a true testament to the power of human ingenuity.

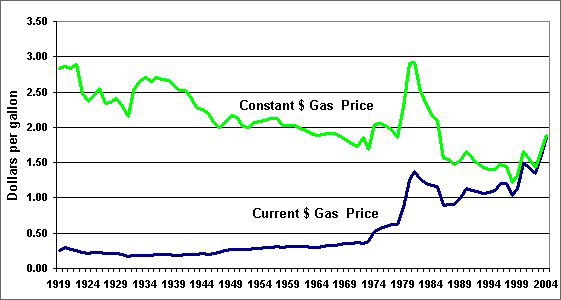

Consider this variant on the Simon-Ehrlich wager, in which an ecologist (Ehrlich) bet an economist (Simon) that the inflation-adjusted prices of five commodities would rise in the 1980s. (All five fell, and Ehrlich lost.) This table (below) shows historical gas prices stretching back to 1919. At 25 cents per gallon in that year, I’ll grant that you’d probably give your right arm for a time machine big enough to fit you and your Toyota Tundra. (Be sure to get your influenza inoculation before you go, however.)

Source: Energy Information Administration (Mar 2005).

But in constant 2010 dollars, that 1919 price of gas was $3.14. True, at the moment we’re paying a bit more—about $3.96. However, keep in mind that in 1919 there were 7.58 million motor vehicles on America’s roads. Today, Americans own about 254 million vehicles. That means that gas prices have risen 26 percent since 1919, while US vehicle ownership has risen 3,250 percent. And those vehicles are being driven more intensively than their 1919 counterparts. We now drive 6,800 percent more miles per year than in 1919, while gas prices have stayed pretty much stable.

Much as I’d love to, it’s beyond my power to conduct a séance and call up the spirits of oil executives and petroleum engineers from 1919. (Besides, if I could raise the dead I’d be concentrating my efforts on Jerry Garcia.) But I bet if I could conjure up oilmen from the past, they’d tell me that thanks to the wondrous, futuristic science of 1919, most of the oil that the laws of engineering and physics would permit man to cost-effectively extract had been discovered, and that supplying 800 million vehicles worldwide would be a mathematical and physical impossibility, by orders of magnitude.

As they say in the investment biz, past performance is no guarantee of future returns. But to this point man has managed to keep up with the demand curve, and just as it’s a certainty that the world’s oil supply is limited, it’s also a certainty that human creativity is limitless.

Comments