Raising MPG Standards: The Second-best Solution to a Gas Tax Increase

(Comstock)

It got surprisingly little press coverage given the degree to which it will affect our lives (thanks, pesky world economic meltdown), but in case you missed it, the Obama administration recently worked out a compromise with the major automakers that will dramatically raise the corporate average fuel economy (CAFE) standards.

The new regulations mandate that the mix of new cars sold in the year 2025 must achieve about 54.5 miles per gallon (though if you read the fine print you’ll see that credits for various other green innovations mean that actual fuel economy will be more like 40 MPG.) For reference, the auto fleet currently on the road gets about 27 MPG. It’s a well-done agreement that will help avoid well-done citizens as global warming accelerates.

Before proceeding, let me note that I am strongly in favor of this policy. The problem of excessive fossil fuel use in transportation is multidimensional: if the issue of global warming doesn’t move you, the thought of Hugo Chavez and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad using our own hard-earned dollars to tweak our geopolitical noses should.

However, it is worth noting that raising CAFE standards is what political scientists and economists call a “second-best” solution; we could be doing considerably better if we thought all of this through more clearly.

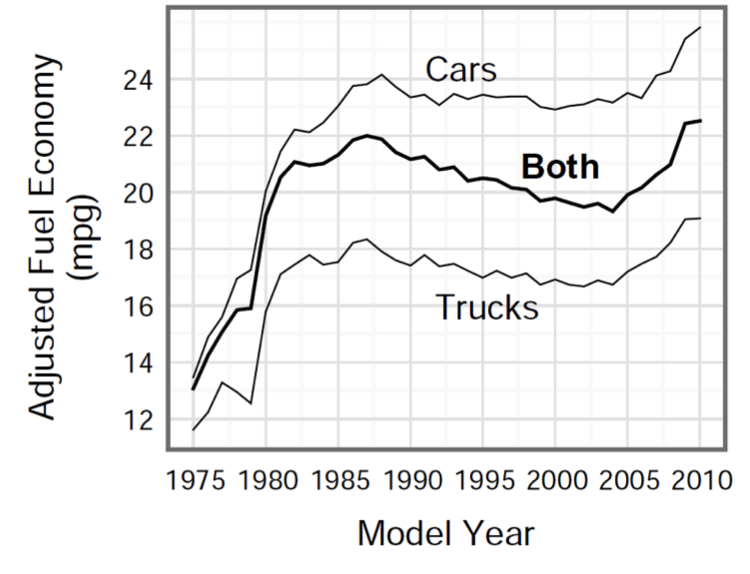

This is not because CAFE doesn’t work; it does. In 1975, a few years before CAFE was implemented, average MPG for new cars and light-duty trucks was 13.1. In 2010 it was 22.5. Can this be attributed to CAFE? To a large degree, yes, as this graph makes clear:

CAFE standards were aggressively increased from 1978 to 1984, and, as the chart above shows, fuel economy responded. However, from 1985 until 2007 CAFE standards were no longer raised meaningfully—and MPG flatlined. The table makes it pretty clear that the CAFE standards created a floor under MPG for a 25-year period, when low gas prices (remember those?) rendered consumers otherwise indifferent to fuel economy.

So what’s the problem with raising CAFE today?

There is a long history of debate on whether “command and control” regulations (like raising CAFE standards) are a good way to bring about change. The other option is the use of price signals—which in this case would be increased fuel taxes—to influence consumer behavior.

Regulations do have some attractive features. For example, we can directly target what, when, and how much improvement we are getting. If we want fuel economy of 55 MPG, we can decree and achieve it with greater certainty than if we try to monkey around with prices.

However, in theory at least, economists generally prefer to do things with price signals as opposed to regulatory standards. Why?

Price signals inflict pain on consumers, but let them figure out what form they want to take it in. They in turn force producers to respond to their (altered) demand, but allow producers leeway in how that demand is met. This allows consumers and producers to change behavior in the most efficient possible manner.

Instead of CAFE, why not just raise the gas tax and let drivers figure out whether they want smaller cars, lighter cars, less powerful cars, more expensive cars, shorter-range cars, or, crucially, cars that are just as heavy, powerful, and cheap—but which get driven less?

This raises the true problem with CAFE. It misses out on a potentially key part of the solution to reducing fuel use: driving less. In fact, ironically, increased CAFE standards will have a perverse and unwelcome effect; better fuel economy will increase the fixed cost of driving (i.e. vehicle prices) but will actually reduce the marginal cost (i.e. fuel expenditures). To a degree, less thirsty cars will actually cause people to increase the number of miles they drive (as I’ve written about here).

With increased gas taxes, on the other hand, less driving will be part of the consumer’s toolkit. Some who absolutely need vehicles with poor fuel economy will have the option of avoiding the tax by driving less instead. As long as their fuel use goes down, why not give them that choice? Greater economic efficiency would result. In fact, the Congressional Budget Office ran the numbers in 2004 and found that cutting fuel use through taxes was considerably cheaper in the long run than raising CAFE.

Reducing driving through a higher gas tax would have other important benefits that improving fuel economy does not, like congestion relief and accident reduction. I personally am more sympathetic to automobility than most of my colleagues in my field, and I have faith that technological ingenuity will deal a powerful and probably decisive blow to our emissions problems. But raising the price of driving above current levels is pretty much a no-brainer; it has support that stretches across ideological lines in the transportation field, even among those like me (and even among carmakers such as GM) who do not see exchanging cars for biodegradable pogo sticks as the only possible solution to our transportation problems.

Another advantage of a gas tax increase is that it would start working today. Since the car fleet takes so long to turn over (according to the US Department of Transportation, automobiles these days stay on the road an average of about 12 or 13 years), it will be a very long time before the new CAFE standards actually translate into meaningful changes in emissions. But increasing the gas tax would have immediate effects.

(Some might object that fuel taxes are regressive and would hurt the poor, and to an extent they would be right. However, the rich drive considerably more than the poor, taking some of the stink off. And paying for many of the new fuel-economy technologies CAFE will result in will be regressive too.)

Thus CAFE might be a second-best policy: good, but not as good as we could have. Then why are we using CAFE while gas taxes stay laughably low by developed-world standards? Obviously, and understandably, because voters hate taxes. If anything, the political winds are blowing towards a lower gas tax, not a higher one.

Comments