What Percentage of Microfinance Loans Actually Go to Business Investment?

(Photodisc)

If someone with a clipboard came up to you in the street and asked you if you secretly harbor racist views, have stolen things in the past, had unprotected sex, or engaged in some other illicit behavior, how likely would you be to tell the truth?

Probably not very. This causes havoc for any researcher who wants to study behavior that may deviate from social norms in some way. A survey technique called “list randomization” allows researchers to calculate the average response to a question in a population, without being able to identify the response of any one individual. In theory this gives people the freedom to answer truthfully, knowing that even the interviewer won’t be able to tell what they answered.

This method has indeed been used to measure hidden racism and sexism among American voters, as well as all sorts of bad behavior by American teens.

In a paper, forthcoming in the Journal of Development Economics, Jonathan Zinman and I apply this approach to the question of how the poor spend their microfinance loans.

Now, to be clear, we are not for a moment passing a value judgment on how people use their loans, or comparing sneaky borrower behavior to racism or crime. But we do expect from other research that whilst borrowers are heavily encouraged or even required to spend their loan on business investment, often they just want to use it for everyday expenses.

So what we did was this:

We asked clients in Group A how many of these three statements apply to them:

- I used part of my Arariwa loan to buy merchandise for my economic activity.

- I used part of my Arariwa loan to buy equipment for my economic activity.

- I shared my loan with another person.

Clients in Group B received these three statements with one additional statement:

- I used at least a quarter of my Arariwa loan on household items, such as food, a TV, a radio, etc.

Given that we expect the number of answers to the first three statements to be the same on average in both populations, we can do a simple comparison of means to figure out how many people in group B said “yes” to that final statement.

So we did this with a few variations of questions, and we also asked people these questions individually and directly on a separate occasion, so we can compare the list randomization method with a regular survey.

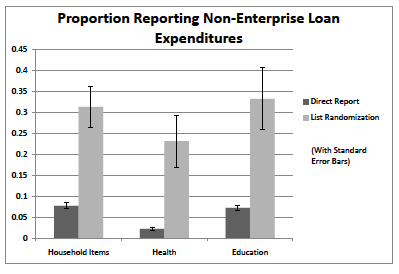

When asked directly, less than 10% of people admitted to spending their loan on household expenses, health, or education.

Using the list randomization, this number jumped to between 30% and 20%.

Clearly borrowers feel a need to pretend to their loan officers, and even independent surveyors, that they are spending more of their loan on business investment than they actually are.

Clearly borrowers feel a need to pretend to their loan officers, and even independent surveyors, that they are spending more of their loan on business investment than they actually are.

Research from other studies increasingly suggests that actually microfinance loans do not have that huge an impact on business productivity anyway, and that much of their benefit is to help smooth out unpredictable income for day-to-day spending. Microloans can have a positive impact even without new business investment or dynamic entrepreneurism. Entrepreneurism is sexy in America. In developing countries, for most, it is synonymous with “I don’t have a job.”

Perhaps it is time for a bit more realism from lenders, and the donors and investors that fund them?

Comments