The Economics of Chicken Feet… and Other Parts

Photo: scaredy_kat

Photo: scaredy_katOur latest podcast, “Weird Recycling,” featured Carlos Ayala, the Vice President of International at Perdue Farms. Stephen Dubner‘s interview with him centered on chicken feet — or chicken paws, as they’re called in the industry. Until about 20 years ago, paws were close to value-less for a U.S. chicken company. But thanks to huge demand in China, paws have become big profit centers. The U.S. now exports about 300,000 metric tons of chicken paws every year. Perdue alone produces more than a billion chicken feet a year, which according to Ayala brings in more than $40 million of revenue. In fact, Ayala says that without the paw, chicken companies would be hard-pressed to stay in business:

DUBNER: Okay. So take me back a little bit, however many years we need to go back to the time before there was a robust export market. Where would those billion plus, if there were that many then, feet be going?

AYALA: So, they’d go to rendering. And it might end up in dog food or something like that. But certainly not for human food. And then in 1991 we started harvesting paws in our first plant and it’s actually a huge upgrade, so, using opportunity costing, and the alternative is almost zero, the upgrade is tremendous. In fact it’s one of the more profitable items for a chicken company right now, are the paws.

DUBNER: And what was the general feeling within Perdue about this idea of creating an export market for… I can tell by the look on your face that it wasn’t greeted with open paws.

AYALA: It’s not going to work! (laughs)

DUBNER: Yeah.

AYALA: Yeah, the idea that we are going to spend a lot of money in infrastructure for the feet? I mean, you know, what are you thinking? But it has turned out to be one of the most profitable items that we have. In fact there’s a lot of chicken companies that would be out of business if it wasn’t for the chicken paws.

DUBNER: Is that right. Perdue included?

AYALA: Um, it would be very difficult for us to survive without chicken paws.

The chicken business has always been a high-volume, low-margin industry. So a few years ago when costs started to rise, mostly due to competition for feed corn from the ethanol industry, chicken companies got squeezed. Ayala writes via email:

With so many chicken companies operating right at the brink, exporting paws for such high prices really does make a big difference to our bottom lines. Thankfully, paw exports are a win/win: The Chinese get more of what they love and we get the employment and profits from a part of the chicken that otherwise wouldn’t have much value.

Even with the paw, some companies have had a hard time staying afloat under the pressure of rising costs and sluggish demand. In 2008, Pilgrim’s Pride, then the country’s largest chicken producer, declared bankruptcy. I spoke with former CEO Buddy Pilgrim, who said that Pilgrim’s Pride started exporting paws to China back in 1995. In just a couple years, the paw went from a niche item to an essential part of the business:

A few years back, only a handful of companies were selling paws into China. Now, everybody does. That tells you how efficient this industry is — when something drives down costs and drives up revenue, you have no choice but to do it; otherwise you don’t survive.

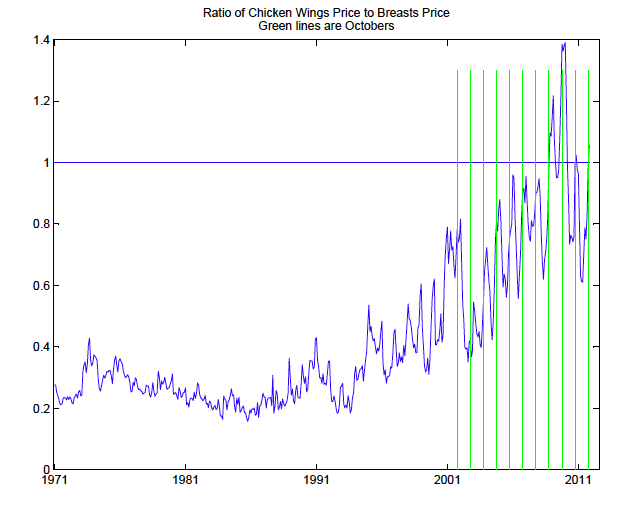

I also spoke with Wally Thurman, an agriculture economist at N.C. State, who’s done research on the economics of chicken wings. Just as Americans prefer turkey breast, we are also fond of chicken breast — but chicken growers can’t produce breasts without all the other parts. Historically, this led to a glut of wings; but recently, demand for wings in the U.S. has risen, and so has the price, as you can see from the following graph that Thurman put together. It shows the price ratio between wings and breasts, based on USDA monthly wholesale data. Notice how the volatility appears to be seasonal. The green lines mark the month of October — which Thurman refers to as the Football Effect.

Comments