How Much Do Music and Movie Piracy Really Hurt the U.S. Economy?

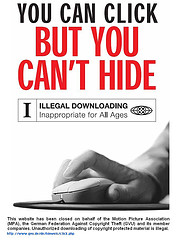

Supporters of stronger intellectual property enforcement — such as those behind the proposed new Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and Protect IP Act (PIPA) bills in Congress — argue that online piracy is a huge problem, one which costs the U.S. economy between $200 and $250 billion per year, and is responsible for the loss of 750,000 American jobs.

These numbers seem truly dire: a $250 billion per year loss would be almost $800 for every man, woman, and child in America. And 750,000 jobs – that’s twice the number of those employed in the entire motion picture industry in 2010.

The good news is that the numbers are wrong — as this post by the Cato Institute’s Julian Sanchez explains. In 2010, the Government Accountability Office released a report noting that these figures “cannot be substantiated or traced back to an underlying data source or methodology,” which is polite government-speak for “these figures were made up out of thin air.”

More recently, a smaller estimate — $58 billion – was produced by the Institute for Policy Innovation (IPI). But that IPI estimate, as both Sanchez and tech journalist Tim Lee have pointed out, is replete with methodological problems, including double- and triple-counting, that swell the estimate of piracy losses considerably.

So what’s the real number? At this point, we simply don’t know. And this leads us to a second problem: one which is not so much about data, as about actual economic effects. There are certainly a lot of people who download music and movies without paying. It’s clear that, at least in some cases, piracy substitutes for a legitimate transaction — for example, a person who would have bought the DVD of the new Kate Beckinsale vampire film (who is that, actually?) but instead downloads it for free on Bit Torrent. In other cases, the person pirating the movie or song would never have bought it. This is especially true if the consumer lives in a relatively poor country, like China, and is simply unable to afford to pay for the films and music he downloads.

Do we count this latter category of downloads as “lost sales”? Not if we’re honest.

And there’s another problem: even in the instances where Internet piracy results in a lost sale, how does that lost sale affect the job market? While jobs may be lost in the movie or music industry, they might be created in another. Money that a pirate doesn’t spend on movies and songs is almost certain to be spent elsewhere. Let’s say it gets spent on skateboards — the same dollar lost by Sony Pictures may be gained by Alien Workshop, a company that makes skateboards.

As Mark Twain once wrote, there are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics. However true that may be in general, statistics can be particularly tricky when they are used to assess the effects of IP piracy. Unlike stealing a car, copying a song doesn’t necessarily inflict a tangible loss on another. Estimating that loss requires counterfactual assumptions about what the world would have been like if the piracy had never happened — and, no surprise, those most affected tend to assume the worst.

Comments