Are Voters Just Rooting for Clothes?

Matthew Yglesias recently noted that the very rich are unhappy with President Obama because he would like to increase the taxes on the very rich. Although this might be true, the number of people unhappy with Obama exceeds the number of people who comprise the very rich. So why are many of the non-rich unhappy with Obama? And why are so many other people quite happy with our current president?

Perhaps the answer is similar to a story frequently told about sports fans.

Back in the early 1990s, a friend of mine declared his hatred of Charles Barkley. At the time, Sir Charles was an All-Star for the Philadelphia 76ers. Sometime after this declaration, though, Barkley was traded to the Phoenix Suns. As a fan of the Suns, my friend changed his tune. With Sir Charles in Phoenix, my friend was now a fan of Barkley.

More recently, LeBron James was an extremely popular athlete in Cleveland. But when he changed his uniform to something from Miami, his popularity in Ohio plummeted.

These stories are not uncommon among sports fans. In fact, Jerry Seinfeld once observed that fans who behave like this are essentially “rooting for clothes.”

Although many fans – and I am one of these – are essentially “rooting for clothes,” the emotions sports generate are quite real. When one of my teams wins, I am quite happy (at least for awhile). And when my teams lose, I am unhappy (for more than just “awhile”). Sports may just be entertainment, but the power to alter our perspective on life – if only for a short time — is quite amazing.

Such power reminds me of how people react to politics.

A few days ago Brendan Nyhan – a professor of political science at Dartmouth — was interviewed on NPR’s Morning Edition (discussing a paper Brendan wrote with Jason Reifler). This interview noted the following:

When pollsters ask Republicans and Democrats whether the president can do anything about high gas prices, the answers reflect the usual partisan divisions in the country. About two-thirds of Republicans say the president can do something about high gas prices, and about two-thirds of Democrats say he can’t.

But six years ago, with a Republican president in the White House, the numbers were reversed: Three-fourths of Democrats said President Bush could do something about high gas prices, while the majority of Republicans said gas prices were clearly outside the president’s control.

The flipped perceptions on gas prices isn’t an aberration, said Dartmouth College political scientist Brendan Nyhan. On a range of issues, partisans seem partial to their political loyalties over the facts. When those loyalties demand changing their views of the facts, he said, partisans seem willing to throw even consistency overboard.

The NPR story doesn’t provide “a range of issues”. But it isn’t hard to come up with such a list. For example, consider these two issues:

- The national debt seems to always trouble the party that isn’t in the White House. When Bush was President (pick your Bush), Democrats were very troubled by the rising national debt. Republicans, though, were relatively quiet. Now that Obama is President, Republicans are extremely worried about the national debt. However, Democrats don’t seem as alarmed.

- What about health care? Mitt Romney implemented a plan from the Heritage Foundation while governor of Massachusetts. Barack Obama backed a very similar plan. Somehow, though, many Republicans are very troubled by Obama’s health care plan (even Mitt Romney!). But many of these same Republicans (even Mitt Romney!) were not troubled by Romney’s health care plan.

One might think that in sports fans are rooting for players. But in reality, many fans are just rooting for clothes. Likewise, we might think that voters are interested in issues. But the above examples suggest that many voters are just rooting for parties. The actual issues each party says they care about don’t seem to be very important. What is important is that the party the voter follows actually wins the elections.

And when this doesn’t happen, as it did for Republicans in 2008, voters become very angry. A Gallup poll seems to capture this point.

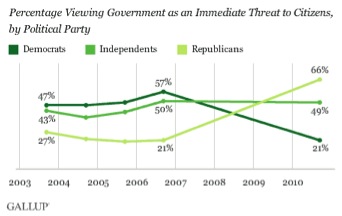

Voters have been asked over time: “Do you think the federal government poses an immediate threat to the rights and freedoms of ordinary citizens, or not?”

Over time, 46 percent of people generally say they believe the federal government poses such a threat. But who voted yes –as the following graph indicates – changed quite dramatically over time.

As Jeffrey Jones noted:

The results suggest that Americans’ perceptions of the government as a threat may be less dependent on broader, philosophical views of government power, and instead have more to do with who is wielding that power. Throughout the Bush administration, Democrats were more likely than Republicans to perceive the government as a threat. Now that a Democratic president is in office, the reverse is true.

One should note that while Democrats and Republicans changed their answer depending on whether their team was “winning”, independents (like me) didn’t change their view very much.

All of this suggests two research questions (and these questions may have already been addressed by someone – in fact, some related research is referred to in a recent New Yorker article by Ezra Klein).

First, it appears that issues may not matter as much as pundits think. So at least (and I am not sure how this can be done) I think we need to see how much voters are rooting for issues and how much voters are rooting for parties. If the latter effect dominates, maybe we need to have sportscasters discuss our elections (and maybe many voters would be happier waving pennants instead of protest signs).

In addition, it would also be interesting to see if sports and politics are treated the same by the human brain. Are these different activities mentally? My sense is that sports and politics really are the same. And again, that suggests the pundits often focus on the wrong issues in discussing why people are angry or happy about election results. Pundits often seem to think it is the actual issues that are driving people’s reactions. But in the end, it might be that the parties – or, following the sports analogy, “the clothes” — that drive people’s reactions.

Let me close with one more observation. If people are just rooting for parties, then efforts to “reach across the aisle” may be quite difficult. Again, think about sports. When LeBron left Cleveland, fans of the Cavaliers suddenly hated LeBron. He was still the same player, but his clothes had changed. The same story seems true in politics.

Regardless of the policies he pursues, many Republicans are not going to be happy with

Obama because he plays for “team Democrat.” And the same may be true if Mitt Romney becomes President in November. As long as he persists in playing for “team Republican,” Democrats will not be happy with Romney.

If this is true, then “reaching across the aisle” may be pointless. Fans of the opposite party are not against the President because he doesn’t agree with them on the issue. They are against the President because he plays for the “wrong” team. And unless he is willing to change teams (i.e. change clothes), he can try to “reach across the aisle” all day and he will never make the other team’s fans happy.

Comments