How to Get the Best out of College? Your Questions Answered

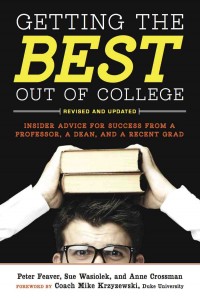

We recently solicited your questions for Peter D. Feaver, Sue Wasiolek, and Anne Crossman, the authors of Getting the Best Out of College. Your questions ran the gamut and so do their replies. Thanks to all for participating. And feel free to check out our podcast on the value of a college education, “Freakonomics Goes to College” (Part 1 here, Part 2 here, and together as an hour-long special).

We recently solicited your questions for Peter D. Feaver, Sue Wasiolek, and Anne Crossman, the authors of Getting the Best Out of College. Your questions ran the gamut and so do their replies. Thanks to all for participating. And feel free to check out our podcast on the value of a college education, “Freakonomics Goes to College” (Part 1 here, Part 2 here, and together as an hour-long special).

Q. Michael Pollan summed up his philosophy of nutrition in seven words: “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.” Do you have similarly pithy advice for students trying to maximize their college experience? Don’t feel limited to seven words – I’m just looking for something aphoristic. –Glen Davis

A. Your choices in college matter more than your choices of college, so choose wisely.

We have found that too many students were more strategic and calculating about getting into college than they are about getting out. It is almost as if they have been programmed to believe that the most important part of college is the name on the degree. We agree that is important, but for most students what makes or breaks the college experience is the choices they make after they have picked their alma mater. The students who really get the best out of college are those who navigate wisely the bewildering puzzle of decisions they will face from the moment they sign their commitment letter until the time they receive their diploma.

Many students–too many students–navigate poorly, but some do wisely. In our experience, it is not necessarily the smartest or the richest or the ones with the most impressive high school resumes who figure out how to navigate the system by the time they reach graduation. After years of watching students unintentionally squander their undergraduate opportunities, we published a book to help students be strategic about their choices, and many of the responses here draw liberally from themes or advice from our book.

Q. If you were heading back to college today, what specific “outcomes” would you manage yourself towards? In other words, what exactly is an “excellent education?” And how would you suggest tracking and monitoring your progress over the 4-year undergraduate experience? –Regret Free Life

A. This is an excellent question (and one we actually encourage students to ask their professors and graduating seniors at their university). So, thanks for asking it. The three of us each had unique educational journeys full of happenstance, rabbit trails, missteps, and successes, yet what we can all agree on the following.

- Since professors are the heartbeat of the university, invest as much time in those relationships as possible, especially early on in the semester when there are fewer demands on a professor’s time than there are later in the semester.

- Select courses based on the strength of the professor teaching it and not simply racing through a list of grad requirements as fast as possible.

- Try to take at least one independent study in your academic career—it will challenge you in more ways than your typical course.

- Take several courses well outside your comfort zone (provided the professor is well-recommended) and a course or two that forces you to think about a subject in ways you never imagined.

- Attend functions where there is a high ratio of faculty and alums so that you can expose yourself to the wide world outside campus.

- Pick two extracurriculars (preferably outside your area of study) and invest your time richly into them.

- As for monitoring your progress, if you have established a set of specific goals and standards going into all this, it will be a clear indicator of how you are growing and meeting them. (More on that in a moment).

- Finally, have fun. Really. College only happens once (hopefully) and there are endless possibilities of creative outlets for fun that you will enjoy retelling at office Christmas parties for years to come. Nothing comes from the nth drunken brawl, but there is a whole host of outrageous pranks and adventures that await if you keep your wits about you.

Q. The largest part of what I learned in college wasn’t the answers to the questions, but how to get the answers to the questions. The ability to do research, to separate the lone nut from the credible source, and the ability to reason out why an answer is correct has proven to be far more beneficial to me than the single answers that any one class would have taught me. –pawnman

A. This is a great comment, and one we hear frequently from students aiming to get the best out of college: that college, properly done, teaches you to think critically. We are believers in the liberal arts ideal, but we recognize that in these trying economic times, everyone–whether holding a liberal arts degree or a career-oriented professional degree–needs to be diligent and strategic in order to secure steady employment and advance in their career. We believe a liberal arts degree can prepare you well for careers in the information age, but we recognize that it doesn’t do so unless you are careful about your course selection and wise about supplementing your curricular education with well-chosen co-curriculars and extracurriculars.

To be successful, you need to be a quick learner who can adapt to rapidly changing environments. Properly done, a liberal arts degree teaches you how to teach and retool yourself for those changes, how to problem solve, and how to critically evaluate new information–all valuable skills in today’s economy. There are, of course, jobs that require a standard menu of knowledge and job-specific skills, and for those a professional degree may be better preparation. But those tend to be entry-level jobs and most people in executive level positions got there because of skills they learned after leaving college. For those people, the enduring knowledge from college were the insights this astute reader pointed out, rather than specific factual knowledge. Whether or not the degree is a direct connection to the career, an increasing number of jobs in the professional environment require college degrees (such as office administration) where in the past they did not.

Q. What do you think about going to college immediately after high school versus waiting a few years? It seems most 18 year olds I know aren’t entirely sure that they are ready to commit to a single career choice, which leads to a lack of focus and wasted time. Is it okay to wait? And if so, how long? –Lucretia

A. It seems we are getting this question more and more these days, as the cost of colleg

e escalates and the undergraduate experience no longer seems such an easy “rite of passage.” Well asked. College should never be the automatic “thing to do because my friends are doing it” at the end of high school; it is an experience that is both costly and rare and should be attempted when a student has reached a certain level of maturity and can take full advantage of it. For some students, the gap year is the way to go simply because they didn’t get into their school of choice. If you find yourself in that scenario, we encourage you to make the most of that year off and strengthen yourself as an applicant for the following year by investing as much hands-on experience in your field of interest as possible; it will make your application stand out among those of high school seniors who will then have less experience and life-perspective than you.

For other students, the gap year is simply a question of maturity. There is no shame in taking a year off to flip burgers, save for tuition, and see what sort of jobs are available without a college degree. In fact, it is to be encouraged. Unfortunately, having the maturity to realize you are too immature to pursue college to its fullest is a bit of a chicken and egg scenario, so this is a decision best entered with the wise advice of parents, teachers, and/or high school counselors who know you best.

Should you decide to take a gap year for whatever reason, be cognizant of two things: that you are spending the time wisely by bettering yourself through your work and saving up for college, and that you—and your high school counselor—cover your bases with tests and recommendations needed for college applications prior to graduating from high school (while your networks and neurons are at their peak).

Q. I’m curious about what advice the authors can give on choosing a major versus preparing for a career. What do you recommend to students who are undecided both in declaring a major and career? Do you suggest prolonging their studies, or perhaps participating in a study abroad program, or something else?

I picked two majors. They were very interesting and I perceived them to be very cool at the time. Then I graduated and went into office administration because it was the only job I could get…but I certainly didn’t need my expensive degree to do it (although most offices require their administrative staff to have college degrees!). I had always imagined starting in office administration, but in a field specific to my major. This is not how it played out.

I realized too little too late that all my time in high school and college was spent on doing well in school and not really preparing for a career, and when it was time to start on a career path I felt like a rudderless ship. It seems like lots of my peers had similar experiences and I was curious if the authors had any comments or advice. –Mrs Indur

I had a similar question. I didn’t really know what kind of career I wanted post college, but I really loved learning languages, so I decided to major in Spanish. Now I have a degree in Spanish, but as a non-native speaker I don’t have a whole lot of career options in that field. Nor do I have much interest in careers like translating or interpreting.

I think that my advice to others would be to figure out the career that they want first and then get a degree in the appropriate field–not to do what I did.

Did I just learn that one the hard way, or is there value in having any degree even if your career doesn’t follow in step? –Claire

How important is it to consider future career options when choosing a major? It seems that certain majors might give you a better chance of getting a job post-college than others. But does that mean you shouldn’t pursue a degree you find interesting, even if you can’t immediately see how it will help you get a job after college? –Adam Lausche

A. We’re going to address these three questions below.

It might seem logical that if you want to pursue a given career, you should get a degree in a program that seems similar; so if business, then economics, or if publishing, then English. But, career paths are not always that linear and it remains unclear why majors and careers seem to have gotten connected to each other in ways that just don’t reflect reality. It may be that the purpose, philosophy and approach undergirding a liberal arts education have never been fully explained nor understood.

In our experience, we have seen students major in unique fields, such as Evolutionary Biology or Political Philosophy, and go on to pursue careers that are seemingly unrelated, specifically to this example management consulting at a prestigious international firm or an executive at a tech company. In fact, if we use this particular tech company as an example (let’s call it ThinkThink), we could also tell you that while ThinkThink prides itself on its high-caliber of engineers, web developers, and marketing agents, ThinkThink came to the recent revelation that the content of its websites is elementary at best and they are now desperate to hired individuals who are talented in written analytics and publishing—say a History or English major. Yes, you heard right: even tech companies need to hire employees with humanities degrees.

It is important to acknowledge that there are a few exceptions to our rule of “any major can lead to any career.” To be an engineer, you need to major in engineering and similarly with nursing. But beyond these two professions, it is quite rare that one’s major has or needs to have any real relationship to one’s career. Hard to believe, we know, but it’s true.

The bottom line is that students need to identify an area of study that they are passionate about and truly enjoy. One way to narrow-down your area of interest is to think about the section of the New York Times you are most inclined to read first. Another strategy might be to think about where you’re likely to wander when you have 20 minutes to linger in a bookstore.

What matters most is your ability to achieve your best in the classroom. We know that success generally comes more readily when we are engaged in a subject we genuinely enjoy. We also know that employers want to hire people who have flourished in their area of expertise while developing the ability to think critically, communicate effectively, collaborate efficiently, and contribute meaningfully. So, the best advice we can offer on the major/career question is this: major in a respected area of study (i.e., not “Scuba Art” or its equivalent at your institution) where you are passionate, eager to immerse yourself in reading and writing on the topic for the next four years, and likely to perform well.

Of course, this advice is premised on the idea that you won’t just be part of the herd in your lecture hall. You will need to be active in your chosen course of study—pursuing independent studies with professors, attending office hours to mine areas of critical thought in the field, and finding internships both in and outside your field to develop depth and breadth. These “advanced” interactions will elucidate how your study can be relevant in unique ways to the workforce, as well as potential ways you can adapt your major to a certain career path by augmenting your coursework with additional well-chosen courses or a minor. This is another area where getting to know your professors is a huge resource. If there is anyone who has tested and seen how a field of study can be applied to life in a myriad of ways, it is profs, and they are often eager to offer some advice.

In addition to faculty, there is another campus resource that you can never access too early as an undergraduate, and that is your career center. Let’s imagine you have achieved the “skills” employers are seeking and there’s still no

clear career path. Or maybe, you have identified a career but you have no idea how to enter that particular job market. This is where your Career Center plays a major role in your academic journey. Visit with a career counselor even as a freshman to learn about resume development, interviewing techniques, internship availability, and work/life balance issues.. Many schools also allow you to access their career center long after graduation.

Q. My husband and I both attended private undergraduate and graduate schools and accumulated quite a bit of student loans. We are hoping to steer our children away from private schools if they choose to attend college. Is there really that much of an educational difference between private and public colleges when it is all said and done? –Julie

A. As we indicated earlier, we believe your choice of college matters less than your choices in college. We know people who have gotten a first-rate education at a less-renowned school and others who have gotten a lousy education at some of the most prestigious schools in the world. To be sure, elite schools–whether private or public–do attract a very high-caliber of students and faculty and have the resources to provide an incredibly rich menu for their customers. But if the customers choose poorly, they end up with a lousy experience.

We do not think it is worth putting your own — or your child’s — financial future in peril by borrowing excessively to pay for the higher priced (usually private, but also out-of-state public) school. If you can afford it, of course, the higher priced school often boasts some advantages: perhaps a more elite faculty, sometimes more focused and motivated students, a more successful/active alumni network, more amenities, and smaller class size (which results in better access to faculty). But a determined and creative student can get many of those same benefits from a discount price school, and so if finances dictate that choice of school, make up the difference with wise choices down the line.

Q. Can you identify any specific skills (academic, social or otherwise) which high schools may be failing to equip young people, thus making it more difficult for them to achieve success in college? Similarly, in what ways might parents be letting down their college-bound kids? –Diana Anderson

A. We understand that most high school teachers have more material to cover than they do time, and as a result study skills don’t make the agenda. Parents can equip their students for success by helping them identify their learning strengths so they can work to them and get their studying done in a manner that is efficient and memorable. Sadly, we don’t have time to cover that here but there are some great books on the subject, not to mention courses online or at local community centers.

As for the social component, we encourage parents to help students identify their personal goals and standards early on, and to hold their principle’s tightly and policies lightly. For example, it will be incredibly hard to live up to the goal “I will always have my work done before midnight” as a policy, since it is rigid and doesn’t always flex with the unknowns of life. However, a principle of “I will organize my workflow such that I will maximize pockets of time to work when my mind is at its best” will be much easier to apply. As early as possible in your academic career—preferably before you hit campus—think through the areas of life that are most important to you: faith, relationships, career ambitions, health, dating, and so on. Design a set of specific goals and standards to guide you through them. It is better to adjust standards as needed than to meander through college aimlessly without them.

For most students, this is a very personal area of self-discovery and it is not necessary for parents to “check their answers.” However, it does offer the potential for thoughtful conversations around the dinner table if your student seems open to discuss. That your student is thinking through these issues and questions prior to arriving on campus places him ahead of the game.

Finally, parents can equip their students to achieve their best on campus by setting up parameters where the student can behave as an adult, with all the responsibilities and privileges that entails. Too often, we see students on campus with the latter but not enough of the former. If you have provided a sort of living allowance for your student, place it in a separate debit account that you replenish each quarter and make it clear ahead of time that those are the only funds open to her use. If he finds himself behind in coursework or needing a boost in class, do not make the call to the professor for him—let him work it out. If she plans to come home for spring break and needs a flight scheduled, or if he has a sinus infection and needs to see a doctor, let your student step up to the plate and take care if it personally. While you will be there for support, encouragement, and advice parents should use the vehicle of the university to launch their children into a mature and successful future.

Q. I’m a non-traditional student returning to school after a long career without a degree. I’m hoping to get over the self consciousness of being older than the vast majority of my classmates. Other challenges are not quite so easy. For instance, I find that I’m approaching my studies like I did my job. I know that goal setting is good, and my goal is to get all A’s. I’m studying for hours on end but I find I’m not absorbing the information and retaining it like I should be. Here we are mid-semester and I’ve developed test anxiety. I know this can be a problem for anyone at any age. I really think part of my problem is, at my age, I have something to prove. This attitude is hampering the real reason I went back to school: to learn. Any tips on how to shift that paradigm? What are you hearing from other non-traditional students? –Ess-Jay’s-Say

A. The great news is that, short of not finding a date to homecoming as readily as you may like, students have shown themselves eager to engage with fellow undergrads regardless of age. In fact, in some of our classrooms we have seen students show a great deal of respect for those who have embarked on college with a bit more of life under their belts. Frequently, as far as the age dynamic is concerned, we find that it is the “older” student who is more troubled by the age difference than the “younger.” There is nothing to be ashamed of in starting college later the cultural norm; if anything, it is to be commended.

What is of greater note in this comment is the latter half, around study needs. And, in this, you are more like your fellow students than you may realize. It is very common for students to go from junior high to high school to college with little to no training in study skills. And, unfortunately, the skills that seemed to work in getting those students through high school—especially around research, test-prep, and cramming—rarely work in college, where a great deal more analysis and synthesis is required. We’ve seen many bright, gifted students fail simply because they were ill-equipped to study effectively by not knowing their learning strengths and how to work to them. So, our advice here would be this: as early in your undergraduate career as possible—even before it begins—invest in a study skills book or course that will help you study smart so you can study well (and study less!). Worthwhile study instruction will train you in active note taking methods that teach you to condense information from lectures and reading into a format that requires you to synthesize (and, hence, learn) the information in the process. Bott

om line: the more active you are with the material you are learning, the better you will remember it.

Q. Is it better to work while going to college (part-time job/internships) or to participate in campus community life (academic and social clubs, sports etc.)? If it’s necessary to work to help cover tuition costs, how might a recent grad communicate to a potential employer (via resume or cover letter) that they weren’t able to participate in campus life activities because they had to work? –Veronica

What would the authors have to say regarding internships and/or opportunities within the university to gain practical experience in their chosen field? In my experience post-college, people care about what you can actually do, so I’m wondering how students can be aware of developing their transferrable/marketable skills. I wish I had been more aware of those things during college. –Lauren Duncan

A. Students need to off-set academic course work by investing in meaningful extracurriculars and a smidge of leisure. While hanging out is a healthy stress reliever, it is some of the most expensive down time you may ever spend, and you may never find yourself with such a wealth of unstructured free time again. At least, not pre-retirement. If finances require, a part-time job is a very valuable way to balance course work and to demonstrate the basic job-skills a future employer will want, like dependability and a willingness to do what is required whether or not it is “interesting.” In fact, even if finances do not require it, we recommend students take at least some sort of part-time work, such as a research assistant for a professor. If you have the luxury of choice, we recommend unpaid internships, which can be a great way to learn about career options. Employers scan resumes and cover letters readily for any prior work experience and will often ask for specific examples during an interview about your leadership, decision making, and work ethic as was evidenced in your jobs as an undergrad. When you narrate your academic story on this front, discuss the positives of how your work experience matured you and made your time both in and out of the classroom that much more valuable.

Additionally, if your time will allow, we think it is very desirable for students to be involved in some sort of extra-curricular activity that will foster a sense of community, build friendships, and develop a new set of life experiences. College is not just preparing students for life, it is life, and there is a deep goodness in a life that is enriched with activities beyond the minimum needed for employment.

Q. My daughter is a freshman in college and intends to become a veterinarian. She is, at least initially, making good grades and is at a school that should prepare her well for graduate studies. We are both keenly aware of how difficult it is to gain admission to vet schools though. My question, is what would be some reasonable options to start thinking about as “Plan B” if she can’t get over the admission’s hurdle? And what can she do during her undergraduate time to both help get into vet school, and to prepare for the plan B scenarios? BTW, I ordered the book as a Christmas gift. –Interested Dad

A. We’ve learned this gem of wisdom both from our own experiences in the school of hard knocks as well as in watching our students attend this same institution: prior to launching into a career that will require extensive schooling, it’s best to invest time in an internship within that field to get some good exposure to the realities of that particular career. Sue often speaks to students on this very topic. She empathizes with the challenge of pursuing a degree only to discover the career path isn’t a good fit. (She graduated from Duke a pre-med but never went to medical school, completed a Masters of Health Administration at Duke then worked in health care for 18 months, earned her J.D. at NCCU and her L.L.M. at Duke and practiced law for nine months, and in 2008 earned her Ed.D from U Penn.) Happily, she found a good fit and those degrees have been put to good use as she has helped advise students how to make the most of their time at Duke for the past 28 years. So, all that to say, your daughter would do well to intern with a vet for a summer—even if unpaid—to make sure she likes the day-in and day-out of it all.

Some fields and programs, as you pointed out, are very competitive and students are wise to aim for that course of study with a Plan B in mind. A well-rounded undergraduate degree will enable a Plan B to be that much stronger, taking classes outside the norm of the major program to develop further critical thinking skills, writing strengths, and perspectives on the human experience. Whether or not students minor in an alternative field, they should challenge themselves with courses in a vastly different area of interest which will make their undergraduate experience richer not to mention increasing their depth and strength as a candidate. We hope she enjoys the gift!

Comments