Last year, Google realized that its employees were eating too much free candy — M&Ms, specifically. So the company conducted a little experiment, and carefully tracked the results. Cecilia Kang, writing in the Washington Post, summaries:

What if the company kept the chocolates hidden in opaque containers but prominently displayed dried figs, pistachios and other healthful snacks in glass jars? The results: In the New York office alone, employees consumed 3.1 million fewer calories from M&Ms over seven weeks. That’s a decrease of nine vending machine-size packages of M&Ms for each of the office’s 2,000 employees.

The company has conducted similar experiments in an effort to reduce consumption of sugary drinks and encourage employees to consume less calories in the company’s cafeterias. “With a company as big as Google, you have to start small to make a difference. We apply the same level of rigor, analysis and experimentation on people as we do the tech side,” says Jennifer Kurkoski, a member of Google’s HR team.

We’ve blogged before about America’s rising obesity rate and how to fight it, but the battle may have just gotten a little easier. A new report from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) shows obesity rates dropping for low-income preschool children in 19 states between 2008 and 2011. From the Wall Street Journal:

The obesity analysis, by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, was based on data from 11.6 million children age 2 to 4. The survey group included children eligible for federally funded programs of maternal and child health and nutrition, such as the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children, known as the WIC program.

The decline was greatest in the U.S. Virgin Islands, where the obesity rate in such children fell to 11% in 2011 from 13.6% in 2008. Drops of more than one percentage point were also seen in Florida, Georgia, New Jersey, Missouri, and South Dakota.

Thomas Frieden, director of the CDC, called the results a “bright spot” and a “tipping point.”

“For the first time in a generation, we’re seeing it go in the right direction in 2- to 4-year-olds,” he said on a conference call with reporters, calling the changes “small but statistically significant.” He was quick to add, “We’re very, very far from being out of the woods.”

Of the 43 states measured, obesity rates for preschool children rose in 3 states and remained the same same in 21 states.

We’ve blogged before about the obesity epidemic, and whether or not it is a recent phenomenon; John Komlos and Marek Brabec have argued that obesity rates actually began rising in the early 20th century. A new study (abstract; PDF) by Paul von Hippel and Ramzi Nahhas looks at 60 years of data on child obesity and finds that the increase in obesity rates started with children born in the 1970s and 1980s. Von Hippel wrote to us in an email:

Intrigued by the conflicting extrapolation results, Ramzi Nahhas and I decided to look at measurements that were actually taken before 1960. We analyzed the heights and weights of children in the Fels Longitudinal Study, an ongoing study that since the 1930s has measured children from shortly after birth until age 18. Most of the children come from the area near Dayton, Ohio, which is not a mirror of the nation but has an obesity rate that is close to the national average.

“Our findings suggest that increases in the real price of one calorie in food for home consumption and the real price of fast-food restaurant food lead to improvements in obesity outcomes among youths. We also find that an increase in the real price of fruits and vegetables has negative consequences for these outcomes.”

That’s from a new paper (abstract; PDF) by Michael Grossman, Erdal Tekin, and Roy Wada, called “Food Prices and Body Fatness among Youths.”

Our recent Freakonomics Radio podcast “100 Ways to Fight Obesity” looked at some of the social costs of America’s increasing rate of obesity. One airline in Samoa is experimenting with defraying some of those costs. It will soon start charging passengers by the kilogram. From The Sydney Morning Herald:

Samoa Air has become the world’s first airline to implement “pay as you weigh” flights, meaning overweight passengers pay more for their seats.

“This is the fairest way of travelling,” chief executive of Samoa Air, Chris Langton, told ABC Radio. “There are no extra fees in terms of excess baggage or anything – it is just a kilo is a kilo is a kilo.”

Our recent podcast on obesity has generated a lot of e-mail. (FWIW, one of the very first podcasts we ever did was also about obesity.) Here’s one interesting angle, from a listener named Mark Gruen:

I just listened to your podcast on 100 ways to fight obesity and while I think there were many quality ideas presented, too many neglected the bodybuilder or strength athlete. I am a lightweight strongman competitor and sometimes eat 10,000 calories in a span of 3-4 hours after training for 5+ hours. These meals are generally high in sugar to support the lost muscle glycogen from my day’s training. I am concerned that once you begin classifying foods as “good” or “bad” you burden people who you did not intend to. The government also does such a poor job with their diet recommendations; I wouldn’t trust them with anything regarding food and diet.

I do love the idea of teaching families and children at school about being malnourished. Unfortunately, I see this as just another way for junk food to add in some vitamins and tell you that you can meet your daily intake just eating their products. Ultimately, people need to wake the hell up and realize that they need to do their own research (not just read a magazine) and determine the right diet for their family.

From Science World Report:

The participants were told to achieve the goal of losing 4 pounds per month up to a predetermined goal weight. The researchers kept track of their body weight every month for almost one year. The researchers told the participants in the incentive groups that they would receive $20 per month if they achieved the goal. And those who failed to achieve the goal would need to pay $20 each month that gets into the bonus pool. Participants in both incentive groups who finished the study were entitled to win the pool by lottery.

The researchers noticed that 62 percent of the participants in the incentive group achieved the goal, while just 26 percent from the non-incentive group hit the target. The mean weight loss of participants from the incentive group was 9.08 pounds and the mean weight loss for the non incentive group was 2.34 pounds.

“The take-home message is that sustained weight loss can be achieved by financial incentives,” lead author Steven Driver, M.D., an internal medicine resident at Mayo Clinic, said in a press statement. “The financial incentives can improve results, and improve compliance and adherence.”

An article in Choices by David R. Just and Brian Wansink illustrates how school administrators can use behavioral economics to nudge kids toward good eating choices and away from the obesity-causing junk food. Just and Wansink point out that administrators often face a difficult choice between nutritious meals and the bottom line:

It may be possible to replace the standard cheese pizza on white flour crust with pizza smothered in spinach, artichoke hearts, and other vegetables on a whole wheat flaxseed crust. But the healthier pizza is more expensive, and fewer children may want to eat it. Hence many school districts walk a tightrope. School districts must increase the health content of their sales while trying to avoid any reduction in their financial viability. Eliminating the less nutritional items often means eliminating the meal budget’s highest margin items. Further, child patronage of the school lunch program is understandably dependent upon schools offering foods that students are familiar with and that they like, and that will satisfy their appetites.

We’ve noted before that the U.S. decline in smoking (among teens as well as adults) has likely contributed to the rise in obesity. In a new working paper (gated), John Cawley and Stephanie von Hinke Kessler Scholder consider the degree to which smoking is a conscious effort to avoid weight gain:

We provide new evidence on the extent to which the demand for cigarettes is derived from the demand for weight control (i.e. weight loss or avoidance of weight gain). We utilize nationally representative data [the Health Behavior in School-Aged Children (HBSC) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES)] that provide the most direct evidence to date on this question: individuals are directly asked whether they smoke to control their weight. We find that, among teenagers who smoke frequently, 46% of girls and 30% of boys are smoking in part to control their weight. This practice is significantly more common among youths who describe themselves as too fat than those who describe themselves as about the right weight.

The derived demand for cigarettes has important implications for tax policy. Under reasonable assumptions, the demand for cigarettes is less price elastic among those who smoke for weight control. Thus, taxes on cigarettes will result in less behavior change (but more revenue collection and less deadweight loss) among those for whom the demand for cigarettes is a derived demand. Public health efforts to reduce smoking initiation and encourage cessation may wish to design campaigns to alter the derived nature of cigarette demand, especially among adolescent girls.

One of the first Freakonomics Radio podcasts we made was an episode about the (surprisingly tenuous) link between obesity and health problems. A new study in The Journal of the American Medical Association finds that “Grade 1 obesity overall was not associated with higher mortality, and overweight was associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality.” Writing for The Daily Beast, Kent Sepkowitz explains:

Compared to people with a normal weight (a BMI less than 25), the overweight (BMI between 25 to 30) had a 6 percent lower mortality rate—and both groups had a rate about 15 percent lower than the obese, especially the very obese (BMI above 35).

The explanation for the finding is uncertain. Perhaps the pleasantly plump but not obese have an extra reserve—a literal spare tire—that confers a survival advantage should they become seriously ill, whereas the lean-iacs do not. Or maybe the thin ones were thin because of a serious illness that, in the course the various studies, killed them. Or maybe the thin ones were thin because they were chain smokers living off Scotch and potato chips. Or just maybe the occasional pig-out does soothe the soul and make for a happier, healthier individual.

(HT: Andrew Sullivan)

The other day, Levitt and I participated in a brainstorming session on how to fight childhood obesity, sponsored by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (FWIW, we recorded the event and will try to turn it into a podcast.)

One topic that got a lot of traction was a targeted tax on sugary drinks and fatty foods. (This is often called a “fat tax” but should not be confused with a tax on overweight people.) Many people in the session were in favor of the idea but a few were skeptical, primarily because such a tax will be tricky to implement well. One objection that I was surprised no one raised: the simple fact that taxpayers might hate the tax and rebel against it to the point where it becomes politically and economically impossible.

In support of the idea, one person reminded us that Denmark recently instituted a “fat tax” on foods containing more than 2.3 percent of saturated fat.

RAND reports on a healthy eating dilemma:

Is eating more fruits and vegetables the key to reducing obesity? A recent RAND study of more than 2,700 adults found that calorie intake from cookies, candy, salty snacks, and soda was approximately twice as high as the recommended daily amount. Consumption of fruits and vegetables, on the other hand, is only 20% shy of recommended guidelines.

Inflation is a term most often employed to describe prices. A too-high inflation rate results in a devalued currency. But what about the inflation of other things in our world? The Economist reports on this trend:

Price inflation remains relatively subdued in the rich world, even though central banks are busily printing money. But other types of inflation are rampant. This “panflation” needs to be recognised for the plague it has become.

Take the grossly underreported problem of “size inflation”, where clothes of any particular labelled size have steadily expanded over time. Estimates by The Economist suggest that the average British size 14 pair of women’s trousers is now more than four inches wider at the waist than it was in the 1970s. In other words, today’s size 14 is really what used to be labelled a size 18; a size 10 is really a size 14.

Leaders of the food reform movement insist on a wholesale remaking of U.S. agriculture, blaming government policy for industrial farming that supposedly adds food miles to our diets and inches to our waistlines. But their solution, a system of local “foodsheds,” wouldn’t save on greenhouse gas emissions and may well be worse for the environment, an argument advanced by economists here and elsewhere. Now it also seems that the federal farm program blamed for worsening obesity has actually kept us skinnier.

That is the finding of agricultural economists Bradley Rickard, Abigail Okrent, and Julian Alston, who report (ungated) in Health Economics that “agricultural policies have discouraged food consumption and mitigated the effects of other factors that have encouraged obesity.”

We seem to be in the midst of a national obsession with obesity. Our latest Freakonomics Radio on Marketplace podcast is about some of the surprising contributors, and possible economic solutions, to the problem. (Download/subscribe at iTunes, get the RSS feed, listen via the media player above, or read the transcript.)

One suspected contributor to obesity, for instance, is the drastic decline in smoking in recent years. It’s great news that fewer people smoke but, according to Vanderbilt economist Kip Viscusi, people who quit smoking tend to gain weight.

French diet guru Pierre Dukan is urging his government to give extra marks in school for a healthy BMI. The Telegraph reports:

“Obesity is a real public health problem that is rarely – if at all – taken into account by politicians,” Mr Dukan told newspaper Le Parisien ahead of the book’s launch.

Mr Dukan said his education plan would be “a good way to sensitise teenagers to the need for a balanced diet.”

He denied it would punish overweight children, saying: “There is nothing wrong with educating children about nutrition. This will not change anything for those who do not need to lose weight. For the others, it will motivate them.”

Obesity — its causes and consequences — is a frequent topic on this blog (and the podcast too). In the podcast, Eric Oliver argued that “the causal relationship between weight and maladies like heart disease, cancer, and even diabetes has not been firmly established.” That certainly strikes some as heresy. In a recent EconTalk podcast, noted heretic Gary Taubes lays out a well-argued position:

Taubes argues that for decades, doctors, the medical establishment, and government agencies encouraged Americans to reduce fat in their diet and increase carbohydrates in order to reduce heart disease. Taubes argues that the evidence for the connection between fat in the diet and heart disease was weak yet the consensus in favor of low-fat diets remained strong. Casual evidence (such as low heart disease rates among populations with little fat in their diet) ignores the possibilities that other factors such as low sugar consumption may explain the relationship.

Anyone for the paleo diet?

We hear increasingly about the healthcare costs of obesity; but what about social costs?

A forthcoming Economics and Human Biology paper (abstract here; PDF here) by Mir Ali, Aliaksandr Amialchuk, and John Rizzo, titled “The Influence of Body Weight on Social Network Ties Among Adolescents,” makes this interesting argument:

We find that obese adolescents have fewer friends and are less socially integrated than their non-obese counterparts. We also find that such penalties in friendship networks are present among whites but not African-Americans or Hispanics, with the largest effect among white females.

We’ve been writing a lot about obesity recently. First, it was this study about projected future obesity rates, then we covered Denmark’s saturated fat tax, which Steve Sexton then criticized for being inefficient. So, if you’re tired of reading fat-related posts on our blog, I get it. But as long as reports like this one from Gallup keep coming out, we’re going to keep writing about them, especially when they include so many interesting conversation points.

Here are the top-line numbers:

About 86% of full-time American workers are above normal weight or have at least one chronic condition. These workers miss a combined estimate of 450 million more days of work each year than their healthy counterparts, resulting in an estimated cost of more than $153 billion in lost productivity per year. That’s roughly 1% of GDP.

The Danish policymakers who implemented the world’s first “fat tax” last week are remarkable not for their directness in addressing the growing Western challenge of obesity, but for their indifference to the plight of the poor, their deference to political correctness at the cost of economic efficiency, and their willingness to punish certain segments of society.

The Danes may have been the first, but headlines throughout the western world assessed the likelihood of other countries to follow, including this one. A fat tax in the U.S. (or the U.K. for that matter) would add to the growing thicket of regulations across local and federal jurisdictions intended to address weight gain and the external costs that obesity imposes on society— both through higher private insurance premiums and ballooning government outlays for the uninsured.

Whether the tax will improve health outcomes is an empirical question that won’t be answered for several years or more.

This week, Denmark begins a large-scale incentives trial of sorts by becoming the first country to impose a nationwide fat tax. From now on, foods in Denmark with saturated fat content above 2.3% will be taxed 16 Danish kroner ($2.87) per kilogram of saturated fat; which works out to a tax of about $1.28 per pound of saturated fat. The tax was reportedly preceded by weeks of Danes stocking up on items like butter, red meat and pizza.

The issue of taxing fatty or sugary foods (and more broadly, the effectiveness of behavioral nudges) has been a topic of repeated discussion on this blog. James McWilliams posted last December on studies which indicate that while taxing sugary sodas reduces consumption, others have shown soda taxes to be ineffective at reducing obesity rates. Proof, McWilliams argues, that taxing specific food items is ultimately ineffective, since consumers can simply substitute sugar from other non-soda sources.

If you’re trying to lose weight, making a small change might help. A new study (summarized by the BPS Research Digest) finds that using the non-dominant hand can significantly reduce the kind of habitual eating that many indulge in without even noticing.

Psychologists invited 158 subjects to watch movie trailers in either a movie theater or a university department meeting room and provided participants (some habitual popcorn eaters, some not) with either stale or fresh popcorn. They found that “in the cinema setting the habitual popcorn eaters ate just as much of the popcorn when it was stale as when it was fresh.

A new study out of Australia shows that children who go to sleep early and wake up early are less likely to be obese. The results, published in the Oct. 1 issue of the journal Sleep, indicate that it’s not so much the amount of sleep kids get, but the times at which they get it that has the biggest impact on their weight.

Americans are fat. The latest obesity estimates reach as high as 30% of the population. The future looks worse. There’s been much hand wringing over the years, with a new television show sprouting up every season imploring the obese to lose weight. But everyone wants to know: why is this happening?

Researchers Charles Baum and Shin-Yi Chou provide a detailed look at the leading indicators of weight, using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth from 1979 and 1997 to compare the habits, similarities and differences between people of the same age – just a quarter century apart. The results aren’t pleasant: the largest effect on our recent weight gain? The decline in cigarette smoking.

The results of a new study by public health researchers at Columbia University and Oxford University forecasts that by 2030, there will be an additional 65 million obese adults living in the U. S., and 11 million more in the U.K. That would bring the U.S. obese population up from 99 million to 164 million, roughly half the population. The findings suggest that as a result, medical costs associated with the treatment of preventable diseases (diabetes, heart disease, stroke, cancer) will increase somewhere between $48 billion and $66 billion per year, in the U.S. alone

The study, published in the Aug. 27 issue of The Lancet, was led by Y. Claire Wang of Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health.

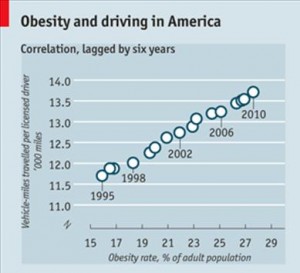

Is higher obesity due to the rise in driving? Perhaps. It’s an intriguing hypothesis. But our friends at The Economist should know better than to report nonsensical correlations. Here’s the evidence they cite (drawn from this entirely unconvincing research paper published in Transport Policy):

Looks impressive, right? (Well, apart from putting the explanatory variable on the vertical axis.) But before concluding that there’s anything here, let’s try a different variable, instead—my age:

Some people really are addicted to foods in a similar way others might be dependent on certain substances, like addictive illegal or prescriptions drugs, or alcohol, researchers from Yale University revealed in Archives of General Psychiatry. Those with an addictive-like behavior seem to have more neural activity in specific parts of the brain in the same way substance-dependent people appear to have, the authors explained.

More here.

The demand for calories increases with age, both because one’s income rises and because one’s taste for good, caloric food has been developed over many years of good eating. I didn’t know what an Esterhazy cake was 40 years ago, but now I can’t resist one if it’s on the menu!

New research by an FDA economist shows that overweight adolescents who are surrounded by overweight family and friends, don’t consider themselves to be overweight.