Coase Goes to War

Photo: Nasser Nouri

Photo: Nasser NouriNicholas Kristof‘s recent column tells the tale of a Libyan officer who wanted to defect:

On Saturday, when I was in Egypt and it looked as if the Gadhafi government might collapse at any time, I had a call from Tripoli: A senior Libyan military officer who had been ordered to attack rebel-held towns was defecting to the rebels instead.

The officer wanted me to report his defection – along with his call for other military officers to do the same – and he had already recorded a video of his defection that I could post immediately on the New York Times website.

I was delighted but asked what preparations he had made to protect his family from retribution. None, it turned out.

I urged the officer to hide his family, to ensure that his wife and children weren’t kidnapped or killed in retaliation. A bit later, I heard back that the officer would accept the risk to his family. I suggested that the officer think this through carefully one more time – and this time the officer actually consulted his wife, who was displeased. The officer sheepishly postponed the announcement of his defection temporarily.

***

My sense is that many Libyan military officers are a bit like that one. They’re uncomfortable attacking fellow Libyans, but they’re also fearful that they or their families will be killed if they refuse. If the outside world signals resolutely that Gadhafi’s ouster is only a matter of time, there’s much more chance that officers will find ways to avoid going down with their leader.

Kristof had previously suggested that the U.S. should assure safe passage for Libyan defectors.

But the officer’s story reminded me of an alternative, more economic, incentive deployed in Iraq, where the U.S. offered defecting officers cash to lay down their arms. As reported by Fred Kaplan in Slate in 2003:

A fascinating piece in the May 19 Defense News quotes Gen. Tommy Franks, chief of U.S. Central Command, confirming what had until now been mere rumors picked up by dubious Arab media outlets-that, before Gulf War II began, U.S. special forces had gone in and bribed Iraqi generals not to fight

“I had letters from Iraqi generals saying, ‘I now work for you,’ ” Franks told Defense News reporter Vago Muradian in a May 10 interview.

The article quotes a “senior official” as adding, “What is the effect you want? How much does a cruise missile cost? Between one and 2.5 million dollars. Well, a bribe is a PGM [precision-guided munition]-it achieves the aim, but it’s bloodless and there’s zero collateral damage.”

A “Smart Bribe” can be a lot cheaper than a “Smart Bomb.”

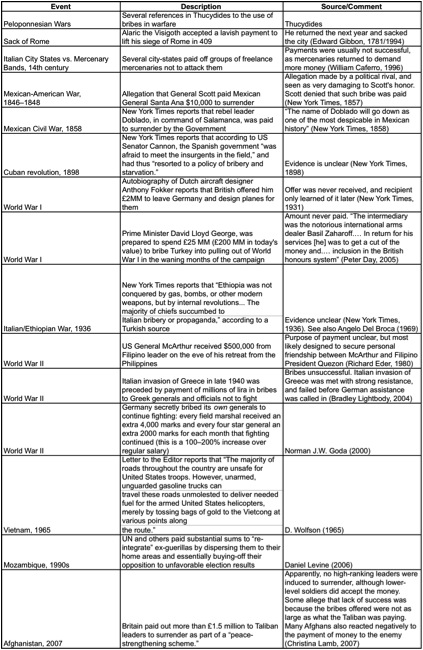

Gideon Parchomovsky and Peter Siegelman (friends and coauthors) have published a fascinating article detailing the pros and cons of bribing enemy combatants to switch sides. Their article even includes this chart providing a quick history of attempted military bribes:

One advantage of cash compensation over Kristof’s recommendation of safe passage is that it might be more credible. Libyan officers can verify a transfer of funds, whereas a U.S. assurance that an officer’s family will be protected may go unfulfilled.

To say that Coasean bribes might be an effective strategy, however, does not necessarily mean that we should offer these blandishments. Inducing officers of another country to mutiny might violate international law. Coasean bribes are almost certainly a legitimate war-time tactic – even though it is a step toward a mercenary fighting force. But soliciting military insurrection by officers of a country with which we are not at war may be a different normative story altogether.

Comments