Why Ranking Charities by Administrative Expenses is a Bad Idea

How does one know whether a charitable donation will make an impact? For this we need a simple formula (easy to write, hard to apply):

Idea X Implementation = Bang for your buck

When I give talks about aid effectiveness, people often comment that they too think this is important. And to make sure they are supporting good charities, they always hone in on the charities’ finances to see how much goes to administrative and fundraising expenses. Charity Navigator, for example, scrubs these numbers and doles out stars to charities that don’t spend “too” much on operations.

Given the title of my book with Jacob Appel, More Than Good Intentions, many assume that they are speaking my language, and that I admire such focus on those numbers too.

But I do not. Those numbers do not tell you what is really happening.

(Hemera)

For assessments of organizations, I like a website called Givewell.org. I may not agree with every assessment they make, but they are the best I’m aware of at doing this. And I’m not sure I could do any better. It is always easier to criticize than to improve. Givewell scrubs for all sorts of information, both publicly available and also through direct communications with charities. They look to understand what the charity does, and how much room they have for growth. Last but not least, they assess whether the idea of what the organization does has been shown to be effective, i.e., the first part of the above formula. (Disclosure: Givewell uses research from Innovations for Poverty Action extensively to gather such evidence, so naturally I agree with many of their conclusions, but we have no formal relationship. Givewell is considering Innovations for Poverty Action for a recommendation.)

So for ratings of organizations—not just ideas—as far as I’m aware, Givewell comes closest to assessing the above formula. When people ask me where to send money to maximize its impact—aside from my beloved IPA of course—this is where I usually send them.

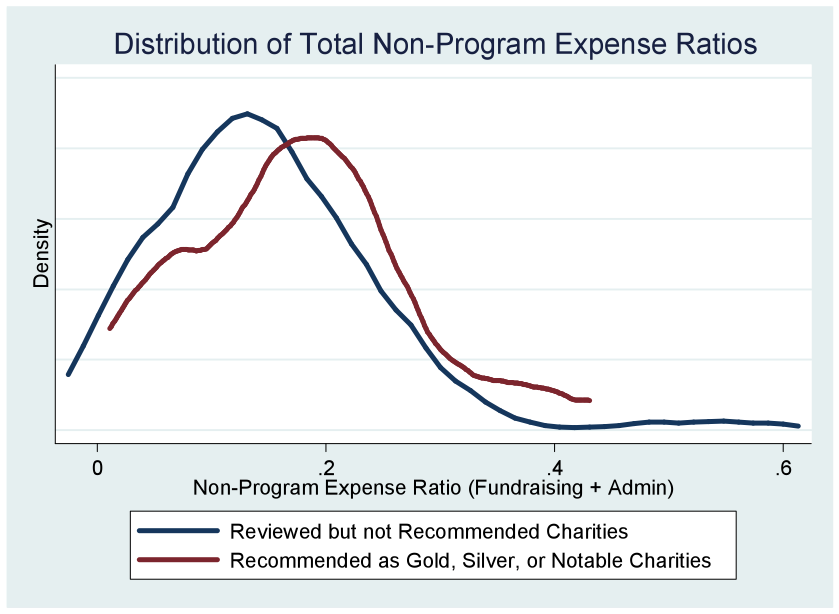

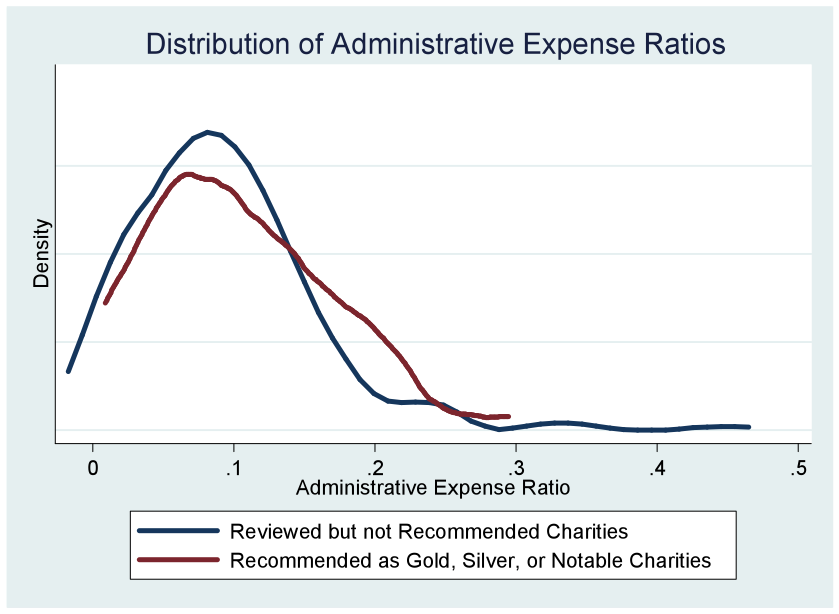

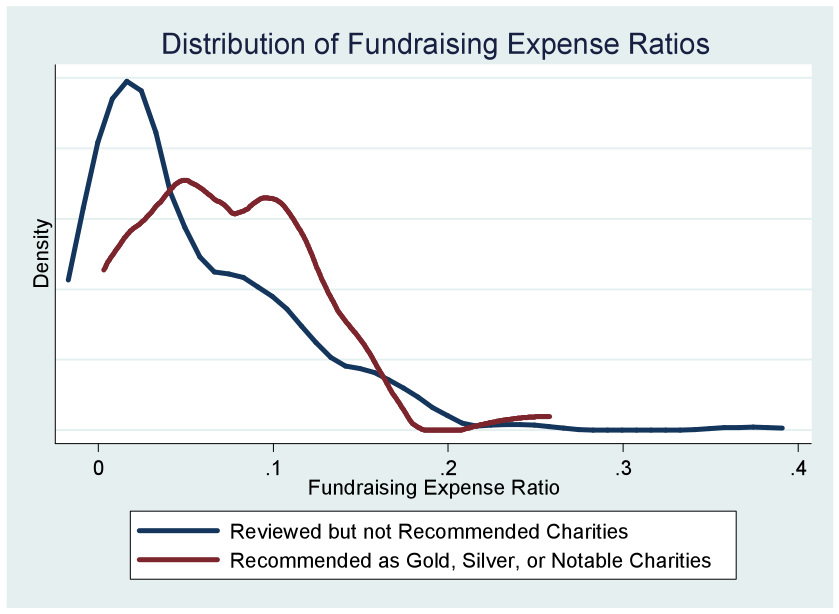

This past week we did a simple exercise. We looked up the fundraising and administrative expenses of each of the U.S. 501(c)3 charities that Givewell rated. We calculated whether those rated better by Givewell had lower administrative and fundraising expenses. They did not. In fact, the opposite is true. The higher rated charities by Givewell have higher administrative and fundraising expenses.

The mean of the fundraising expense ratio for charities (the money spent on fundraising divided by the total expenses of the entire organization) that earned a gold, silver, or notable rating by Givewell (41 charities) is 0.073, while that of the charities reviewed by Givewell but not ranked well (253 charities) is 0.054 (p-value of 0.05, i.e., statistically significant at the 95% level). The mean of the administrative expense ratio for charities that earned a gold, silver, or notable rating by Givewell is 0.102, while that of the charities reviewed by Givewell but not ranked well is 0.092 (p-value of 0.35). Adding administrative and fundraising together, the mean ratio for charities that earned a gold, silver, or notable rating by Givewell is 0.174, while that of the charities reviewed by Givewell but not ranked well is 0.147 (p-value of 0.11).

See below for three charts which show the distributions (the red line (“recommended” in some way) is consistently to the right of the blue line (“reviewed but not recommended”).

Does this mean ignore expenses entirely? No, I’d say that huge outliers—charities whose expenses are much higher than their peers’ doing similar work—should be approached with caution. But within the reasonable expense band that most charities are in, I simply ignore these numbers. There are many reasons why. To touch on one: they are really easy to manipulate. Just Google “Feed the Children” and see the accounting shenanigans behind gifts-in-kind (amongst other nasty stuff). In short, overvalue the gifts-in-kind you receive and voilà, your program services just got bigger, holding everything else constant (and the corporation gets a bigger tax write-off too). Garbage in, garbage out. For more on this, check out Uncharitable by Dan Pallotta.

What sources do Freakonomics readers like to use to guide their decisions?

Comments