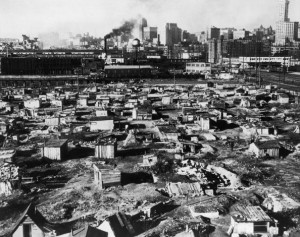

The Controversial Legacy of Slum Clearance

(Photo by FPG/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

A new study by Vanderbilt economist William J. Collins and Ph.D. candidate Katharine L. Shester looks at the long-term economic impact of the ambitious (and highly controversial) Housing Act of 1949, which used federal subsidies and the powers of eminent domain to “revitalize” American cities, i.e., to clear out the slums. By the time the program ended in 1974, 2,100 distinct urban renewal projects had been completed using grants that totaled about $53 billion (in 2009 dollars).

In one of the rare papers to collect and analyze data related to the program, Collins and Shester come up with a positive picture of its effects – at least in some ways. The authors are clear that the ugliness involved with pushing people out of low-income housing was the reason the program was shut down, and that their results do not “imply that the dislocation costs for displaced residents and businesses were unimportant.” From the abstract:

We use an instrumental variable strategy to estimate the program’s effects on city-level measures of median income, property values, employment and poverty rates, and population. The estimates are generally positive and economically significant, and they are not driven by differential changes in cities’ demographic composition. The results are consistent with a model of spatial equilibrium in which local productivity is enhanced.

Cities that did the most slum-clearing or “urban renewal” had a higher increase in property values, income and population compared to non-participating cities. The results also show that these cities maintained roughly the same demographics, and did not push low-income residents out of cities, but rather redistributed the population.

The results suggest a far less dismal legacy for the U.S. urban renewal program than is commonly portrayed. It appears that cities that were allowed to engage more actively in urban renewal posted better outcomes in 1980 than they otherwise would have in terms of property value, income, and population growth. Moreover, these results were not achieved by merely pushing residents with low human capital levels out of the city.

Though that’s surely cold comfort to those low-income residents turned out of their apartments, and the neighborhoods destroyed for civic centers and right-of-way.

Here are some highlights from the data:

- As of June 30, 1966, the last date on which detailed data are available, approved projects had cleared (or intended to clear) over 400,000 housing units, forcing the relocation of over 300,000 families, just over half of whom were nonwhite. The proposed clearance areas included nearly 57,000 total acres (90 square miles), of which about 35 percent was proposed for residential redevelopment, 27 percent for streets and public rights-of-way, 15 percent for industrial use, 13 percent for commercial use, and 11 percent for public or “semi-public” use.

- There is strong evidence of a positive correlation between economic outcomes in 1980 and years of potential participation in the urban renewal program. For instance, 5 extra years of enabling legislation is associated with approximately 4 percent higher median property values and 1 percent higher family income.

- [A] $100 per capita difference in grant funding is associated with a 2.6 percent difference in 1980 median income and a 7.7 percent difference in 1980 median property value. The median city in our dataset received $122 per capita in funding, and so the coefficient estimates imply an economically significant impact.

Comments