International Aid and Mobile Cash Transfers

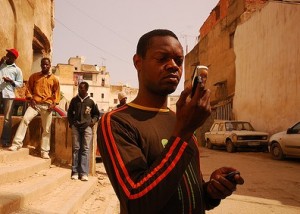

Photo: Swiatoslaw Wojtkowiak

Photo: Swiatoslaw WojtkowiakWe’ve blogged before about the many applications of mobile phone technology in developing countries, especially when it comes to mobile banking. In much of the developing world, particularly in Africa, mobile phones are thriving in remote villages, while access to electricity, clean water, schools and government services is weak at best; yet cellular service is strong.

A new research paper by Jenny C. Aker, Rachid Boumnijel, Amanda McClelland and Niall Tierney analyzes the effectiveness of yet another mobile application gaining strength in the developing world: cash transfer programs. After a drought in Niger in 2009 and 2010, Concern Worldwide, an international NGO, provided “unconditional cash transfers to approximately 10,000 households during the ‘hungry season,’ the five-month period before the harvest and typically the time of increased malnutrition.”

Instead of distributing cash in the usual way, the NGO conducted a randomized experiment: one-third of targeted villages received a monthly cash transfer through a mobile system called zap; another third received manual cash transfers, and the remaining third received manual cash transfers plus a mobile phone.

The old-fashioned manual method proved particularly burdensome. “[C]ash was counted into envelopes and transported via armored vehicles to individual recipients,” explain the authors. “Rather than distributing the cash in each village, a central village location was chosen for groups of 4-5 villages. Program recipients had to travel to their designated location on a given day to receive the cash transfer.”

By contrast, zap recipients simply received their payments by phone, although they did have to “take the mobile phone to an m-transfer agent located in their village, a nearby village or a nearby market to obtain their physical cash.”

The results were promising. From the abstract:

We show that the zap delivery mechanism strongly reduced the variable distribution costs for the implementing agency, as well as program recipients’ costs of obtaining the cash transfer. The zap approach also resulted in additional benefits: households in zap villages used their cash transfer to purchase a more diverse set of goods, had higher diet diversity, depleted fewer assets and grew more types of crops, especially marginal cash crops grown by women. We posit that the potential mechanisms underlying these results are the lower costs and greater privacy of the receiving the cash transfer via the zap mechanism, as well as changes in intra-household decision-making. This suggests that m-transfers could be a cost-effective means of providing cash transfers for remote rural populations, especially those with limited road and financial infrastructure.

While the zap method of transfer did require an upfront investment (in mobile phones, zap accounts and transfer fees), it’s easy to imagine those costs decreasing as mobile phones become more widespread in even the poorest countries. The study’s authors caution that more research is needed on the “broader welfare effects” of the zap transfer method, but it seems inevitable that NGOs will someday dispense much of their cash (if not all) by mobile phone, particularly to recipients in difficult-to-reach locations.

So readers, what do you think? Are there any drawbacks to this method of dispensing aid?

(HT: Chris Blattman)

Comments