Swallowing the Whistle: A Guest Post by Tobias Moskowitz

The following is a guest post by Tobias J. Moskowitz, co-author of Scorecasting: The Hidden Influences Behind How Sports Are Played and Games Are Won

The following is a guest post by Tobias J. Moskowitz, co-author of Scorecasting: The Hidden Influences Behind How Sports Are Played and Games Are Won, now out in paperback. Moskowitz is a University of Chicago financial economist — you may remember Steve Levitt mentioning the book or the Q&A with the authors on the blog. They are also regular contributors to the “Football Freakonomics” project.

Swallowing the Whistle

By Tobias J. Moskowitz

With the upcoming Super Bowl this Sunday pitting the Giants against the Patriots again (they last faced off in 2008), who could forget the most infamous play in Super Bowl history? And in case you did forget, the image of David Tyree reaching back until he was nearly parallel to the field and snatching the ball with one hand and pinning it to his helmet has been either shown or referred to at least 150 times on ESPN and the NFL Network in the last week — and we’re still a week away from the game!

The play was extraordinary, no doubt about it, but perhaps the most interesting aspect of that play was something rather ordinary that happened well before Tyree made his remarkable grab (it was the last catch of his career by the way—one hell of curtain call!), something that is much more likely to be a factor in the upcoming game.

If you rewind the play to a few frames earlier, you will find Eli Manning all but bear-hugged by a cluster of Patriots defenders — Richard Seymour and Adalius Thomas, in particular — who had grasped a fistful of the right side of his number 10 jersey. Manning’s progress appeared to be stopped. Quarterbacks in far less peril have been determined to be “in the grasp,” a call made to protect quarterbacks that awards the defense with a sack. However, next time you view the footage, pay close attention to what happened in the backfield before Manning made his great escape. Mike Carey, the head official, started on the left side of the field but then backpedaled and found an unobstructed view behind Manning. A few feet away from the play, alert and well-positioned as usual, eyes lasering on the players, Carey appeared poised to declare Manning sacked. And then . . . nothing. It was a judgment call, and Carey’s judgment was not to judge.

“Half a second longer and I would’ve had to [call him in the grasp],” says Carey. “If I stayed in my original position, I would have whistled it. Fortunately, I was mobile enough to see that he wasn’t completely in the grasp. Yeah, I had a sense of ‘Oh boy, I hope I made the right call.’ And I think I did. . . . I’m glad I didn’t blow it dead. I’d make the same call again, whether it was the last [drive] of the Super Bowl or the first play of the preseason.”

Others aren’t so sure. Reconsidering the play several years later, Tony Dungy, the former Indianapolis Colts coach and now an NBC commentator, remarked: “It should’ve been a sack. And, I’d never noticed this before, but if you watch Mike Carey, he almost blows the whistle. . . . With the game on the line, Mike gives the QB a chance to make a play in a Super Bowl. . . . I think in a regular season game he probably makes the call.” In other words, at least according to Dungy, the most famous play in Super Bowl history might never have happened if the official had followed the rule book to the letter and made the call he would have made during the regular season.

It might have been a correct call. It might have been an incorrect call. But was it the wrong call? It sure didn’t come off that way. Carey was not chided for “situational ethics” or “selective officiating.” Quite the contrary. He was widely hailed for his restraint, so much so that he was given a grade of A+ by his superiors. In the aftermath of the game, he appeared on talk shows and was even permitted by the NFL to grant interviews — including one to us, as well as one to Playboy — about the play, a rarity for officials in most major sports leagues. It’s hard to recall the NFL reacting more favorably to a single piece of officiating.

And why not? The men in the striped uniforms and white caps did what they usually do at a crucial juncture: They declined to make what, to some, seemed like an obvious call.

If this is surprising, it shouldn’t be. It conforms to a sort of default mode of human behavior. People view acts of omission — the absence of an act — as far less intrusive or harmful than acts of commission — the committing of an act — even if the outcomes are the same or worse. Psychologists call this omission bias, and it expresses itself in a broad range of contexts.

Most of us probably would contend that telling a direct lie is worse than withholding the truth. You might feel a small stab of regret over not raising your hand in class to give the correct answer; but raise your hand and provide the wrong answer, and you feel much worse. The first principle imparted to all medical students is “Do no harm.” It’s not, pointedly, “Do some good.” Our legal system draws a similar distinction, seldom assigning an affirmative duty to rescue. Submerge someone in water, and you’re in trouble. Stand idly by while someone flails in the pool before drowning, and— unless you’re the lifeguard — you won’t be charged with failing to rescue. In most large companies, managers are obsessed with avoiding failure rather than missing opportunities. Errors of commission are often assigned responsibility, but people are rarely held accountable for failing to act, even though those errors can be just as, if not more, costly.

This same thinking extends to sports officials. In our book, Scorecasting: The Hidden Influences Behind How Sports Are Played and Games Are Won, we examine how omission bias affects refereeing. We find evidence in every sport — baseball, basketball, hockey, soccer, and football — that officials are systematically more worried about making wrong calls than wrong non-calls. As a consequence, they “swallow the whistle” when the game is on the line. Especially during crucial intervals, officials often take pains not to insinuate themselves into the game. In the NBA, there’s even an unwritten directive: “When the game steps up, you step down.”

It’s a noble objective, but it expresses an unmistakable bias, and one could argue that it is worse tha

n the normal, random mistakes officials make during a game. Random referee errors, though annoying, can’t be predicted or gamed and tend to balance out over time, not favoring one team over the other. A systematic bias is different, conferring a clear advantage (or disadvantage) to one type of player or team over another and enabling us — to say nothing of savvy teams, players, coaches, executives, and, yes, gamblers — to predict who will benefit from the officiating in which circumstances.

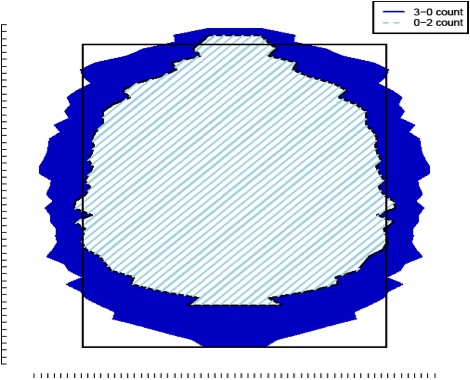

One clear example we show in baseball is that the umpire’s strike zone shrinks considerably when there are two strikes on the batter and widens considerably when there are three balls in the count. Many pitches that are technically within the strike zone are not called strikes when that would result in a called third strike. Conversely, the umpire’s strike zone expands significantly when there are three balls on the batter, going so far as to include pitches that are more than several inches outside the strike zone. To give an extreme example, the strike zone on 3–0 counts is 188 square inches larger than it is on 0–2 counts in MLB. That’s an astonishing difference, and it can’t be a random error.

Plot of the empirical strike zone (defined as any pitch called a strike at least 50% of the time by MLB umpires) on 3-0 vs. 0-2 counts. The black box represents the actual rules-mandated strike zone.

In basketball, hockey, soccer, and the NFL, we also find that the rate of officials’ calls, especially judgment calls, goes way down near the end of tight games and the bigger the stage. How do we know this is referee bias and not just the flow of the game? Because non-subjective calls that require little judgment — such as delay of game and shot clock violations, where everyone in the stadium can see a giant clock indicate that time has expired or, in the case of the NBA, the entire goal lighting up red — do not decline as the game gets tight or nears its end. Officials seem to systematically swallow the whistle on judgment calls and let the players determine the outcome. As fans, we may want that, too, but keep in mind it means the rules of the game aren’t being applied uniformly.

Since the Super Bowl is arguably the biggest stage and since pundits are predicting a tight game, don’t expect too many calls near its conclusion, and who knows, we might end up with another infamous Super Bowl play that perhaps should not have happened.

Comments