The Retirement Robbery

Since putting email back in its corral, I’ve turned some recovered time to reading actual books in print — the latest being Retirement Heist: How Companies Plunder and Profit from the Nest Eggs of American Workers by Ellen E. Schultz. If a nation of sheep shall beget a government of wolves, then the lesson from Retirement Heist is that today the shears are sharpened with numbers.

Retirement Heist is, as one blurb describes, a “meticulously researched and gripping as a crime thriller.” Each chapter explains, with detailed research data and outrage-generating examples, yet another method corporations use to steal retirement benefits and mask the theft behind accounting shenanigans. It is one of the few books (since Cadillac Desert) to describe outrageous behavior so well that I threw it across the room.

In calling the tricks accounting shenanigans, I might be unfairly maligning the accounting profession. From the joke on page 54, I learned the difference between accountants and actuaries:

A CFO is interviewing candidates for a job as a benefits consultant. He calls the first one, an accountant, into his office and asks, “What’s two plus two?” The accountant says, “Four.” The CFO sends him away, calls an actuary into the room, and asks, “What’s two plus two?” The actuary closes the door, pulls down the blinds, then leans in and whispers, “What do you want it to be?” He gets the job.

Among the wonders worked by these benefits, consultants are teaching companies how to degrade benefits without reprisals. One method is to make a series of changes, each perhaps illegal but small enough not to be worth a lawsuit. Then make a big degradation. If anyone sues, the defense is that, by not protesting the earlier changes, employees gave implicit consent to this change.

Among such explanations of wholesale deception, there are a few heartening stories — for example, of Fred Loewy (page 191), an 80-year-old former French resistance fighter and rocket engineer who retired from Motorola and found a $100-per-month error in his pension payment. He politely asked for the amount to be reviewed. After years of denial and runaround, including certified letters sent back unclaimed (the company later described its behavior in court as exhaustive cooperation), he filed a federal lawsuit. It got certified as a class action because the same mistake had been made with hundreds of other retirees. A few months before Loewy died, the retirees won a settlement of $11 million.

One’s joy is tempered because federal pension law (ERISA) includes no punitive damages, not even for such egregious behavior. The damages are limited to rectifying the errors. Thus, it is in the corporate interest to make “mistakes.” The worst that can happen is that an ex-resistance fighter and rocket engineer turns up, and you end up paying some of your legal obligations. Mostly, however, no one notices, or they die while waiting for a speck of justice.

The savings from the shenanigans hardly go to Mother Theresa’s orphanage. Rather, as Retirement Heist demonstrates, they go to outsized pensions and other benefits for executives (such as pumping up the stock price, thereby enriching executives with stock options). For some companies, one-third of their pension obligations were just for the executives.

Mirroring the degradation of retirement security described by Schultz, I’ve been under three pension systems, the second slightly worse than the first, and the third a lot worse.

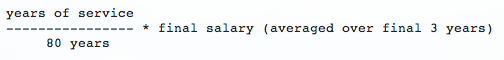

My first real job was at the University of Cambridge, where I was part of the Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS). I contributed 6.25 per cent of my salary, and Cambridge University contributed 18.75 per cent (triple matching). This total of 25 per cent went to USS, an independent organization set up by the UK universities. At retirement, USS provides a lump-sum payment and a final-salary pension calculated as follows:

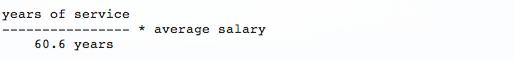

After 8 years of service, I left the USS scheme and came to MIT. The MIT plan had a similar pension formula:

After 8 years of service, I left the USS scheme and came to MIT. The MIT plan had a similar pension formula:

For short-term employees, whose average and final salaries are comparable, MIT’s plan with its smaller denominator is better than the USS plan. For long-term employees getting raises at 2-3 per cent (if you can find any), whose final salary is significantly greater than the average salary, the USS plan is better. Furthermore, the USS plan was multi-employer. One could take an academic position anywhere in the United Kingdom and still accumulate years of service.

Both the USS and MIT plans are a traditional, defined-benefit pension where the retiree gets a defined amount at retirement. As Retirement Heist describes, these high-quality plans are the plans that companies have been eliminating (except for their executives).

My third and current plan is a defined-contribution plan. I put in 2.5 per cent of my salary and Olin College puts in 7.5 per cent. This total of 10 per cent contribution is mine to use upon retirement. Great news! However, the 10 per cent that is contributed is a lot less than the 25 per cent that USS uses to provide a decent pension. Furthermore, all the risk is mine. When the invisible hand slaps the world upside the head, turning 401(k)’s into 201(k)’s, it’s my problem. Another 25 years of service on this latest and greatest plan, which I am sad to say is better than what many people in the United States have, might provide me something comparable to what I get for 8 years of service on a real, defined-benefit pension plan. No wonder defined-contribution plans have been called “The 401(k) ripoff.”

After learning of the scams and frauds described in Retirement Heist, I realized perhaps the biggest benefit of the USS scheme: The contributions were real money, and managed by a separate entity whose sole purpose was ensuring that it could pay the pensions it promises. Under the USS system, there are no incentives to shift pension funds toward executive compensation or to use them to pump up the stock price (not least because USS has no stock).

In corporate America, the same entity prov

iding pensions has many other needs, so it uses the pension fund as a casino as much as the law allows and often beyond (with hardly any penalty). As but one example, bankruptcy of the company mostly destroys the workers pension and the company’s pension obligations, giving companies an incentive to go bankrupt.

If the degradation of pensions were done to cure cancer or bring safe drinking water to all the world, I might be happy to make the sacrifice. However, executive compensation and stock-price manipulation are hardly charitable works. The moral of all this: Unless you are an executive with huge payments extracted from the 99 percent, you are being ripped off, and Shultz shows the how and why.

Comments