Why My Favorite American Cities Have a Chinatown

Relatives from South Africa were visiting and we got to talking about which cities to visit in America. I shared my list: San Francisco, New York, Boston, Washington, DC, Seattle, and Philadelphia. Each city has a Chinatown. Coincidence? Or maybe the connection is just that I like Chinese food. Indeed, our family has been going to a favorite dim-sum restaurant most every week since moving to Boston seven years ago.

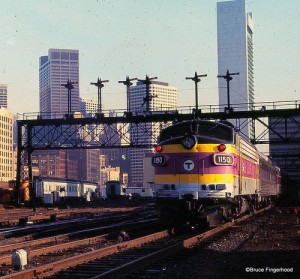

Then the larger connection came to me. Chinatowns were made by Chinese laborers building the railroads (when the laborers had finished this vast public-works program, the Chinese Exclusion Act barred most Chinese from emigration to or citizenship of the United States). Having a Chinatown marks a city as of the railroad era, built up before the wide deployment of the automobile. As Lewis Mumford said, “The right to have access to every building in the city by private motorcar in an age when everyone possesses such a vehicle is actually the right to destroy the city.” Cities with Chinatowns had enough roots to escape carmageddon.

Does the exception prove the rule? One exception might be Los Angeles, where I lived for five years as a Ph.D. student. Despite the endless summer, I happily left it for the rain of England. But Los Angeles has a vibrant and historic Chinatown (under the gun of Walmart, whose externalities and rent-seeking behaviors are described by Al Norman in his Q&A with Sudhir Venkatesh).

Maybe Los Angeles disproves the conjecture that a Chinatown means a great city. However, as Jonathan Kwitny of the Wall Street Journal reported:

Though hard to believe now, Los Angeles once had a heavily used urban rail system extending from Newport Beach and Long Beach through downtown, on to Pasadena, and into the San Fernando Valley—perhaps the best system in the country. The conspirators bought and dismantled it in stages during the 1940s.

Yes, that C-word! Streetcars once climbed the San Gabriel mountains, bringing Angelenos for a day of walking and hiking. The conspiracy, led by GM, ruined a city that had been built up, and had built its Chinatown, before the automobile. The exception does prove the rule—in the original meaning of “prove” as “test” (which survives in “proofing the yeast”). And the rule passes. (For fun, try it out on Canadian cities.)

Comments