A Unified Theory of Why Women Earn Less

John List and Uri Gneezy have appeared on our blog many times. This guest post is part a series adapted from their new book The Why Axis: Hidden Motives and the Undiscovered Economics of Everyday Life. List appeared in our recent podcast “How to Raise Money Without Killing a Kitten.”

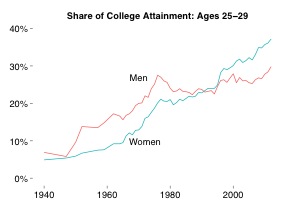

When it comes to the year 1991, history books will undoubtedly focus on the first Gulf War and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, but at least domestically, the biggest change was one you probably never heard about: 1991 was the first year that women overtook men in college attainment, a trend that has only gained steam since. Today 37.2% of women between the ages of 25 to 29 have a four-year college degree or higher versus just 29.8% for men.

When it comes to the year 1991, history books will undoubtedly focus on the first Gulf War and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, but at least domestically, the biggest change was one you probably never heard about: 1991 was the first year that women overtook men in college attainment, a trend that has only gained steam since. Today 37.2% of women between the ages of 25 to 29 have a four-year college degree or higher versus just 29.8% for men.

Yet for all the academic achievement by women, men still earn a higher wage for equivalent jobs and continue to dominate the highest ranks of society. Senior management positions? Only one in five are held by women. Fortune 500 CEOs? Just 4% and fewer than 17% of the seats in Congress are held by women.

Scholars have long theorized about the reasons why women haven’t made faster progress in breaking through the glass ceiling. Personally, we think that much of it boils down to this: men and women have different preferences for competitiveness, and at least part of the wage gaps we see are a result of men and women responding differently to incentives.

Being experimentalists, we understood that without actual evidence, this was just a conjecture. Determined to test our idea in the field we launched a large-scale field experiment on Craigslist where we posted ads for an administrative assistant gig we needed to fill. The experiment was conducted with Jeff Flory and Andreas Leibbrandt as coauthors. We received responses from nearly 7,000 interested job seekers from cities all over the U.S.

After a job seeker touched base with us, we gave them more details on the way they’d be compensated. Then we asked them to provide some basic information if they wanted to be considered for the position. Half the job seekers were told that the job paid a flat $15 per hour. The other half were told they would be paid $12 an hour but they would compete with a co-worker for a $6 per hour bonus (so that both ads would pay workers an average of $15 per hour).

What’d we find? Women were 70% less likely than men to go after the job if it had the competitive pay scale. This result accords with the broader insights from laboratory experiments that others—Muriel Niederle, Lise Vesterlund, Aldo Rustichini, etc.—have found. Of course, this estimate doesn’t apply to every type of job and every type of person in the country, but it does underscore the fact that, when it comes to competition at a potential job, women aren’t always interested in leaning in.

If you want to explore our world further, take the Why Axis Challenge: visit www.thewhyaxischallenge.com, post a photo of your copy of The Why Axis, and be entered to win prizes, including a meeting with Uri, John and Freakonomics author Steven Levitt! Be sure to stay tuned for more posts to come, which will give a glimpse into more ‘undiscovered economics.’

Comments