How to End (Price) Discrimination

John List and Uri Gneezy have appeared on our blog many times. This guest post is part a series adapted from their new book The Why Axis: Hidden Motives and the Undiscovered Economics of Everyday Life. List appeared in our recent podcast “How to Raise Money Without Killing a Kitten.”

The passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act was a landmark civil rights bill. It afforded the disabled protections against discrimination that were similar to earlier landmark civil rights bills. In particular, the bill targeted two types of discrimination. One type was the discrimination against the disabled motivated by hatred or disgust. For example, one provision targeted employers that denied employment opportunities to those that truly qualified. Other parts of the bill focused on ensuring a level playing field for the disabled, like one requirement for businesses to make readily achievable retrofits to their businesses to afford the disabled access.

When economists think about the causes of discrimination, they tend to lump them into these two categories. The first is called animus discrimination, which is the type of discrimination we tend to associate with the treatment of African-Americans in the early 20th century. The second is called statistical discrimination, which is discrimination motivated by statistical trends associated with groups. For example, women tend to pay less for auto insurance because they are safer drivers.

The distinction between animus and statistical discrimination might seem mundane, but for policymakers it’s crucial. Everyone tends to support policies aimed at reducing discrimination, but how should policies tackle discrimination? To answer that question you have to know what’s causing the discrimination in the first place.

In fact, this is the exact pitch we gave to a disabilities-rights group interested in working on testing the causes of discrimination with us, and the experiment we ended up running yielded a shockingly simple way to remove discrimination for the disabled.

But before we get ahead of ourselves, here’s how the experiment ran: First, we recruited several men between the ages of twenty-nine and forty-five to act as our secret agents. Half these men used wheelchairs and drove specially equipped vehicles. The other half were non-disabled, but in all cases the individuals hopped into a specially equipped vehicle for the disabled with a fresh ding on the side and headed to Chicago-area repair shops.

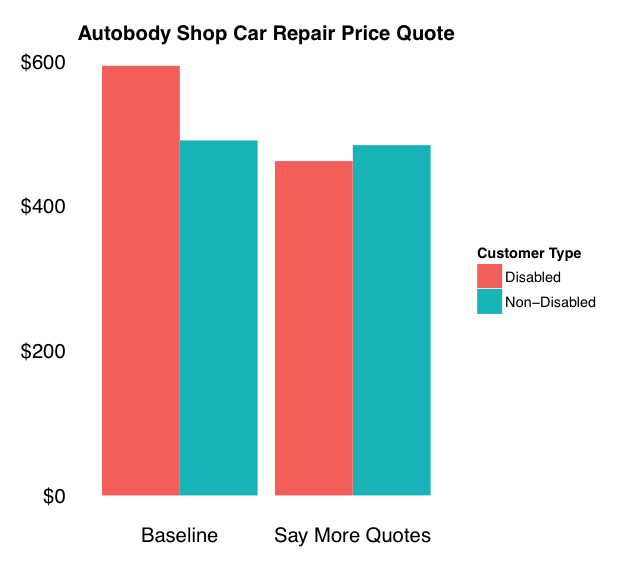

When our secret agents got to an auto repair shop they simply asked for a price quote to fix their car. What we found initially was shocking. The disabled were given quotes 30 percent higher than the quotes given to non-disabled for the exact same repair!

When our secret agents got to an auto repair shop they simply asked for a price quote to fix their car. What we found initially was shocking. The disabled were given quotes 30 percent higher than the quotes given to non-disabled for the exact same repair!

Curious about the extent to which car repairman were motivated by hatred or just profit motive, though, we did one run of the experiment where both types of our secret agents got a quote and told the repairman that they were, “getting three price quotes today.”

What did this extra sentence do? Well the figure shows that for the able-bodied subjects, their price quotes didn’t change at all, but for the disabled they plummeted. Furthermore, the difference in prices for the disabled and abled disappeared.

It turned out that mechanics were just making an economic calculation when they gave out price quotes. Put differently they were engaging in classic, blatantly unfair, economic discrimination by taking advantage of a customer’s disability. Luckily, policymakers may already have the solution for this sort of discrimination in place. The Americans with Disabilities Act has forced businesses to facilitate easy access for the disabled, making a task like obtaining multiple quotes possible. Now we just need to make it predictable enough for mechanics to catch up.

If you want to explore our world further, take the Why Axis Challenge: visit www.thewhyaxischallenge.com, post a photo of your copy of The Why Axis, and be entered to win prizes, including a meeting with Uri, John and Freakonomics author Steven Levitt! Be sure to stay tuned for more posts to come, which will give a glimpse into more “undiscovered economics.”

Comments