The Music Industry Copyright Battle: When is Owning More Like Renting?

A rash of recent news articles (like here and here) have noted that in a little over a year, an obscure provision of U.S. copyright law takes effect – one which allows songwriters and musicians to exercise their “termination rights” and take back from the record labels many thousands of songs they licensed 35 years ago.

So, for example, Boston will be able to take back Don’t Look Back. Gloria Gaynor can repo Love Tracks, and Elvis Costello can reclaim This Year’s Model. Less auspiciously, Kiss guitarist Ace Frehley can reclaim his entire solo album. (The music industry may not mind losing this one.) And every Jan. 1, a whole new crop of artists looking to lay claim to their termination rights will appear.

The music industry, already reeling from online piracy and digital downloads, is fighting back against what they see as the looming loss of their property—and the huge profits that still come from some of these records. Why would Congress create a system where, 35 years after making a record that no one knew for sure would be a hit, musicians could take back control—and profits—over the best-selling songs?

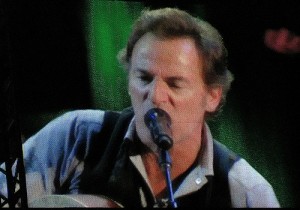

Photo: Andrea SartoratiBruce Springsteen is hoping to reclaim ownership of his 1978 album “Darkness at the Edge of Town.”

Photo: Andrea SartoratiBruce Springsteen is hoping to reclaim ownership of his 1978 album “Darkness at the Edge of Town.”In general, if you decide to sell or perpetually license a piece of property, you can’t later take it back, no matter how much you might want to. So If I sell my house and two years later the city decides to build a lovely public park in my neighborhood, the value of my former house may rise substantially. But no one contends that I can take the house back, or that I’m due a bonus payment from the lucky buyer. A deal is a deal.

So why the exception for copyright owners? It is sometimes said that the ultimate market value of creative works is among the hardest to predict, and so fairness requires a bonus for authors when a deal proves particularly rich. But that explanation cannot suffice standing alone, because it is equally an argument for giving a bonus to buyers when deals prove (as they often do) valueless. And yet only the musicians can terminate rights – not the record labels.

A more important justification observes that musicians often face much more competition than record companies. There are, or at least have been traditionally, many more songwriters and performers than there are record labels. So labels enjoy a degree of leverage in negotiations with musicians. This is a better justification than the first, but it’s still weak.

Think for a moment about the economic effect of the termination provision on the behavior of parties to copyright transactions. Because buyers can expect, on average, to make lower profits when the law contains the termination provision, they will offer less in the initial transaction. Thus, sellers will be more willing to accept less, because they know that if a work later proves valuable, they can terminate and demand some additional payment. So the most likely effect of the termination provision is to force deal prices down across the board. Interesting.

Is this good? Depends. If we consider the situation of musicians, not really. The termination provision forces initial prices down for all artists. It then enriches a few fortunate enough to have produced works of enduring value (or profit). A termination provision, in other words, is like a lottery ticket—and like lottery tickets, the vast majority of ticket holders get nothing. The most successful musicians are the last ones in need of aid, but the net effect of the termination provision is to transfer wealth from unsuccessful (the lottery losers) to successful artists (the lottery winners).

Put differently, the termination provision is a regressive tax. And in that light, the “fairness” justification for the termination provision is less than overwhelming.

Now, the music industry is making none of these arguments in the current sparring over termination rights. Instead, record companies have hired legions of lawyers to argue in court that songs are “works made for hire” – i.e., that the musicians were employees, and therefore the songs belong permanently to the record companies, not the musicians.

That argument will play out over the next few years, but even now it looks dubious. Musicians are not “employees” of the record companies the way fry cooks are employees of McDonald’s. They are independent contractors who create their art and then license it.

However weak the music industry’s legal claims may be, the termination system remains a poor idea—one that, in the interest of fairness, actually transferred money from those who needed it most to those who need it least.

Comments