There Will Be Rich Always: Finding a New Way to Think About Income Inequality

On Monday, Aaron Edlin and I published a cri de coeur op-ed in the New York Times calling for a Brandeis tax, an automatic tax that would put the brakes on income inequality. In the next few days, Aaron and I will be publishing a series of posts explaining more about our rationale and providing more details on how a Brandeis tax might be implemented.

There Will Be Rich Always

By Ian Ayres & Aaron Edlin

In one of the more memorable lyrics from the musical Jesus Christ Superstar (based on Matthew 26:11), Jesus tells his disciples “There will be poor always.”

The same is true of the rich. There will always be a top 1 percent of income earners. But what it takes to be rich can change drastically over the course of even a single generation. In 1980, you would have had to earn at least $158,000 to be a one-percenter; but by 2006 the qualifying amount had more than doubled to $332,000. (You can produce an estimate of your own household income percentile – albeit using a different definition of income that produces a much higher 1 percent cutoff – at this wsj.com site.) The rise is not due to inflation as both these numbers are expressed in inflation-adjusted, constant 2006 dollars. The rise is due to the simple fact that our richest Americans in real terms were earning much more money.

The economic changes in the past 30 years were a rising tide that did not lift all boats. Over the same period the median household income remained relatively constant, at roughly $50,000. While inequality has increased in most wealthy economies, the United States, according to the OECD, remains among the most unequal.

The vast shift in national income toward our richest 1 percent is especially vivid if their income is expressed in terms of the median household income. Indeed, an important goal of our op-ed was to suggest a new unit of measure, “medians” to help us think about what it means to be rich. In 1980, if you earned 3.8 medians, you were in the top 1 percent, but by 2006 even the poorest in the 1 percent club earned 6.9 medians.

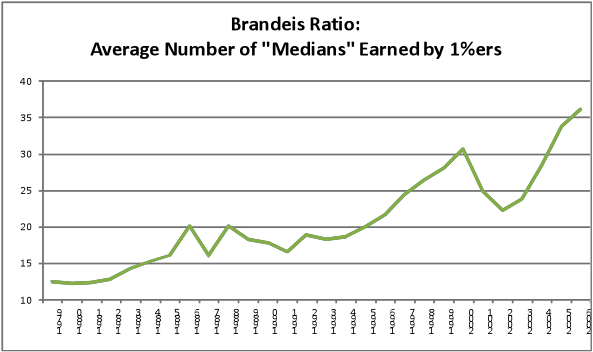

What we call the “Brandeis Ratio,” the average income of the richest 1 percent (which includes the billions earned by the lucky few) has grown even more disproportionate. As shown in the chart below, in 1980, one-percenters on average made 12.5 medians, but in 2006 (the latest year in which data is available) the average income of our richest 1 percent was a whopping 36 medians.

Define Rich?

In August 2008, the Reverend Rick Warren asked each of the presidential candidates Barack Obama and John McCain to:

Define “Rich.” Give me a specific number. Where do you move from middle class to rich?

The candidates’ answers, given at what might be the high-water mark of income inequality in our nation’s history, reveals the difficulties that both parties have talking about economic class. McCain was visibly uncomfortable in naming a number:

So I think if you’re just talking about income, how about $5 million? So, no, but seriously, I don’t think you can — I don’t think, seriously, that — the point is that I’m trying to make here, seriously — and I’m sure that comment will be distorted — but the point is, the point is, the point is that we want to keep people’s taxes low and increase revenues.

In part, McCain was reluctant to name a figure which might be used to construct a new bracket to raise taxes – so he picked a large number; very large in terms of “medians.” McCain suggested that you would have to earn an income that is 100 times the median household income in order to “move from middle class to rich.”

Obama in contrast gave a much more reasonable answer:

Here’s how I think about it, and this is reflected in my tax plan. If you are making $150,000 a year or less as a family, then you’re middle class, or you may be poor. But 150 (thousand dollars) down, you’re basically middle class. Obviously, it depends on region and where you’re living. . . . I would argue that if you’re making more than 250,000 (dollars) then you’re in the top 3, 4 percent of this country. You’re doing well. Now, these things are all relative, and I’m not suggesting that everybody who is making over 250,000 (dollars) is living on Easy Street.

Obama should be given points for easily relating his cutoff of $250,000 to those Americans who are “in the top 3, 4 percent of this country.” But we are a little troubled at Obama’s describing family incomes of $150,000 as still being in the middle class, when these families earn 3 times what the median households earn. Survey data reveals contested definitions of middle class, and there is evidence that Americans disagree with Obama. In a 2007 study conducted by NPR, the Kaiser Foundation, and the Harvard School of Public Health, 51 percent of respondents did not consider a family of four with an $80,000 income middle class – that consensus rose to 65 percent when the family income rose to $100,000.

We as a nation seem to have trouble facing up to the fact that most Americans earn far less than what it takes to be comfortably middle class. We would do well to give more emphasis in our definition of the middle class to incomes earned by average Americans. Our aspirational middle class is making it too easy for us to forget what is happening to our actual middle class.

A larger goal of our op-ed is to spark a different kind of debate about income inequality. Rev. Warren was crafty in that he only asked the candidates the descriptive question: what is rich. But we want people of goodwill to ask a normative analog. In our op-ed, we claim that it “would be bad for our democracy if one-percenters started making 40 or 50 times as much as the median American.”

Is there any Brandeis Ratio that would give concern to this year’s Republican candidates? We suspect they would be unwilling to express unease with any level of inequality produced by market forces. They would argue that any government attempts to lean against inequality by taxing job-creators would invariably produce distortions (including sending one-percenters abroad, beyond the reach of our tax laws) that would end up making things worse off for middle class Americans. This is a debate worth having, but we cannot begin unless we find a way to engage in normative debate about income and wealth inequality. Asking whether the government should be concerned about the rapid rise of the average o

ne-percent income from 12.5 to 36 median incomes is our way to provoke a more explicit debate.

Seeing Medians

Framing income inequality in terms of “medians” is also part of a larger goal of making the median household incomes more salient. As we said in our op-ed, “Part of our goal is to change the way politicians speak about income equality. Framing the income of the wealthy in relation to the median income will help us all keep in mind the relative success of the middle class.”

It might even be useful to describe other things in terms of medians. A new Cadillac Escalade will run you 1.4 medians. A year’s tuition at Yale Law School is about .88 medians. We might even restructure government salaries so that they automatically adjust with the median. Paying a congressman 3.5 medians (instead of the current $174,000), might make it easier for our representatives to remember and even pursue the interests of their typical constituents.

To raise the prominence of the median measure, government could standardize a “mi” symbol. A stylized icon figure representing a median earner might even be more effective in letting us remember that to earn 36 median incomes is to earn as much as 36 actual households:

Comments