Episode Transcript

My guest today, Wendy McNaughton is an artist and graphic journalist her work appears frequently in The New York Times, and she’s had a handful of bestselling books. But the main reason I wanted to talk to her today is that she has produced a stunningly touching book called How to Say Goodbye.

MACNAUGHTON: It’s called How to Say Goodbye. I’d grab it off the shelf and be like, “Oh, it’s going to tell me how to do this thing.” But then the first thing you learn is there’s no right way to do this. There’s no one way to say goodbye.

Welcome to People I (Mostly) Admire, with Steve Levitt.

There is no doubt that Wendy and I are very different types of people. Conversations between opposites can be really good or really bad. Let’s see if we can figure out how to talk to one another.

* * *

LEVITT: As I headed over to this interview, I tried to think about the last time I had talked with an artist — someone who earns their living with a pencil or painting or sculpture. And this will be shocking to you, but the last conversation I remember happened 25 years ago.

MACNAUGHTON: Are you kidding me?

LEVITT: I just don’t have any artists in my world.

MACNAUGHTON: Really?

LEVITT: But I bet you don’t talk to a lot of economists either, though, right? When’s the last time you talked to an economist?

MACNAUGHTON: That’s a really good point. No, I don’t. We can be each other’s exceptional friends. The universe might have to rearrange itself. Something magical is going to happen.

LEVITT: Well, I’m sure something will. I mean, I was trying to think, why don’t economists talk to artists? One theory is that capitalism doesn’t treat artists very kindly and economists are usually defenders of capitalism. And that might be one reason that we’re pushed away from one another.

MACNAUGHTON: Maybe. I have a lot of friends who are journalists or scientists. There seems to be more of a natural intersection there. I don’t know, and the fact that I’ve never even noticed that before really says something.

LEVITT: It does because you are a seer, right? I mean, part of what you do is you see things as an artist. You see things other people can’t see in the world around us.

MACNAUGHTON: Yeah. Now I’m actually a little intimidated by our conversation realizing I’ve never really spoken to an economist before.

LEVITT: I think economists — at least me, I’m a little bit afraid of artists because, number one, I tend to like things that I can quantify. And art, it’s hard to quantify. And number two, economists are very literal. Economists look at the world and then what we try to do is strip away everything complicated down to a handful of mathematical equations, which are obviously nothing like the real world, but maybe capture some element of it. And I know artists strip away, too, but I think everything the economists strip away is what the artists try to keep and everything the economists keep, the artists try to get rid of it. That would be my hunch.

MACNAUGHTON: And yet, we’re still both using our set of tools that we’ve honed over the years — and they’re pretty blunt in their own ways and limited. But yeah, you’re probably trying to exclude all the things that make life interesting to me.

LEVITT: Yeah, that’s right.

MACNAUGHTON: In my work sometimes I do, like, diagrams and I do like my version of data sets. They are hand drawn and completely inaccurate, but humanly true.

LEVITT: So, I’m breaking out of my “fear of artists” mode to talk to you today because you have created something that’s incredibly beautiful and that touched me so deeply. It’s a book of illustrations and prose and it’s called How to Say Goodbye. How do you describe that book?

MACNAUGHTON: It’s a really personal project and it’s interesting to begin to talk about it more openly. It is kind of a combination between a conversation starter and a poem. It’s like a visual poem, but it’s also an introduction to how we can approach sitting with people at the most vulnerable time of their lives and when we’re very vulnerable too when someone we love is dying. And I’m somebody who’s a big doer. I’m a big kind of fixer. “Let’s make everything okay in the room.” And I didn’t know what to do and I didn’t know how to be. And this is the little book that I wish that I had had to at least open up a space for me to quiet down, to look at what’s going on, be present, and just really pay attention and be there with the person I love.

LEVITT: The book is in part based on your experiences in the Zen Hospice, but it sounds like the genesis of this started before that with a more personal grieving process.

MACNAUGHTON: Yeah. Most of the drawings are made within what was at the time a guest house of Zen Hospice Project, which is a caregiving hospice group. I had an artist-in-residency there for about a year. And I drew everything in the house and the residents who were there, who were dying, and their families. And I interviewed the caregivers. And the book is a combination of those drawings and the wisdom, the words that I heard from the caregivers. There are also drawings of my own aunt in there. Before the residency, my aunt passed away, and she’s that person for me who was the first person I just loved very deeply and was able to be there as she was dying. And I didn’t know what to do with myself, but I’m a drawer. And I don’t draw from imagination; I draw from life. Drawing for me is a vehicle for looking closely at things, but it’s also a way for me to look at things that I’m scared of. And I didn’t know what to do, but I had my sketchbook and my pencil and my aunt had been a kindergarten teacher and an artist, and I’d been drawing her actually for some time, so she was cool with it, I knew. And I drew her each day leading up to her death. That opened up a space of presence and also curiosity. And the little book combines those drawings done in the guesthouse and of my aunt as well.

LEVITT: Did you reach out to the Zen Hospice or did they reach out to you? How did that connection get made?

MACNAUGHTON: The darn universe. They reached out to me. Literally within, I think, a day or two of my aunt passing, I got a call from them and they asked if I was interested in this residency. And when the universe speaks, you’d be foolish not to listen.

LEVITT: So, I know B.J. Miller, who’s a palliative care doctor who’s associated with Zen Hospice. But for people who aren’t familiar with it, could you just explain? It’s a really unique take on dying.

MACNAUGHTON: Zen Hospice Project was an organization. They had a six-bed guest house, where people would go who were in hospice care, and it was a really unique hospice setting that approached the residents as a human being, you know, as a person who was at a stage in their life, not who was at the end of their life. It was a chapter of their life. And they considered things like aesthetics. You know, they had beautiful kitchen, where there was always food being made. So smell of food being cooked was there. There was always fresh flowers there. There was beautiful art on the walls. And so it was a meaningful place for the residents to be and also for their families to be. It since closed and transformed into the Zen Caregiving Project, and I believe they’re still doing trainings with that perspective in mind.

LEVITT: It’s so rare in modern medicine for there to be someone other than a loved one around. I mean, my experience with modern medicine is: it’s mechanized, it’s sterile, everyone’s in a hurry. How did the patients — did they understand you? How did they react to your just being?

MACNAUGHTON: I mean, like anybody else, some people were really excited that there was an artist around and that we could talk about drawing and they were excited to be drawn. And some people said, “What the heck? I have no interest in being drawn. Get out of my room.” There was one woman in particular named Jenny, who was an artist herself, who was always making beautiful beaded paintings. And I was so excited to engage with her and maybe collaborate on some stuff, and she was not having it. She’s like, “I’m doing my work. And by the way, I don’t really like your drawings very much.” I’m like, “Okay, that’s fine.” There was another woman, Catherine, who herself had drawn in her life, and I asked Catherine if I could draw her, and she agreed. And she asked if she could draw me at the same time. She didn’t have much dexterity, you know, in her hands. But it didn’t really matter how my drawing or her drawing turned out. It was that experience of sitting together and looking closely at each other and also being seen by one another. That was a moving experience for both of us. This book, it’s kind of a meditation on being present and using drawing to be present with somebody. Because essentially drawing is just slowing down and looking really closely. And when we’re doing that, we’re paying attention to another person in a way that we don’t in our lives. Because whether you’re a doctor and you have a long list of people who you’re going to see later and stuff to take care of, or you’re just somebody who has a meeting that you have to rush off to, we’re trying to, like, achieve an end goal all the time. But when we really slow down and use something like drawing, we can be present with each other in a really different way. And at the end of life, I can’t think of a more important time to do that.

LEVITT: It’s interesting because in the world of the iPhone, photographs have become so dominant, so easy, so high quality, and I hadn’t really paused to think about the difference between a drawing and a photograph. Partly you mentioned it takes time, but it’s more than that. I think we have this sense of: a photograph is objectifying and a drawing is something different.

MACNAUGHTON: It sure can be. When somebody puts a camera in my face, well, literally, you’re putting a piece of machinery in between two human beings in order to document a relationship. That’s an interesting way to do it. When I’m drawing somebody, I’m holding my sketch pad at waist high, so there’s an open channel between me and the person I’m drawing. And then there’s a physical document of that looking experience. And to me it’s kind of magic. It holds the energy of that time and of that exchange.

LEVITT: Do you tend to talk to people while you draw them or is there silence?

MACNAUGHTON: I tend to use drawing as a way to talk to people. It’s a great conversation starter, but if I’m really concentrating, I don’t really hear much. Are you a drawer at all? Have you ever drawn?

LEVITT: No. I’m physically incapable of drawing. It’s interesting because I talk a lot about math and how people declare themselves they’re “not a math person” and how we need to fight that. But I’m really not a drawing person. And I remember the moment at which that became clear to me. And it would’ve been in either fifth or sixth grade. I had an art teacher. And we were drawing monsters and I had the arms coming out of the side of the body rather than the shoulders. And with complete disdain, she said to me, “My God, you’re old enough to have the arms come out of the shoulders, aren’t you?” I remember what I said was, “Well, it’s a monster, the arms don’t have to come out of the shoulders.” But what I actually thought was, “God, she’s right. Of course the arms should come out of the shoulders.” I hadn’t thought about the body very well. But look, I’m not very good at making a pencil or a pen go where I want it to. Now, obviously, that’s not the only prerequisite for being an artist, but I would say I 100 percent self-identify as a person who cannot draw. And only under the duress of the demands of a five-year-old will I ever draw anything. And usually it’s crumpled up by my five-year-old in disgust, and she goes to her mother to get a better version.

MACNAUGHTON: Okay. You just said, “I know I tell people all the time who say they can’t do math that they can, but I really can’t do art.” And you’re saying that to an artist who literally, like, says that to people all the time. You can! You absolutely can. Just a couple things happened that made you think that you can’t. I mean 95 percent of the world has this, that around the age of five or six or something like that, some adult put some judgment into it and said, “You’re doing it wrong.” And you were so right when you said, “Look, it’s a monster.” But there was some adult who probably had some other adult when they were five tell them there’s a right and a wrong way to do things and that drawing’s all about the outcome, not the process, and that your imagination is wrong. Like, way to close off an entire way of thinking and being in the world, you know? Five-year-old you is still waiting there. At any time you can come out and draw that monster, because drawing is like the number one way that kids can build up this flexibility and adaptability and all these kinds of things that are, like, a monster with arms coming out of the side of its body. And when that’s closed down early, it makes us think that we can and we cannot do things. So I just want to offer that if we took the idea of you doing a good drawing — whatever that means — a good drawing off the table, and said: “Drawing is actually an experience that you have with your body, and just experience that and see after 10 minutes how you feel,” I think you’d have a really different experience.

LEVITT: Okay. So, I’m going to take that as my homework for tonight.

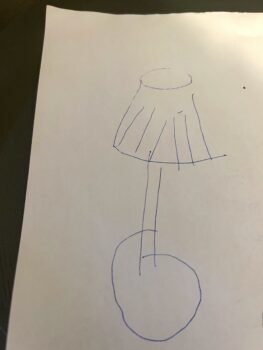

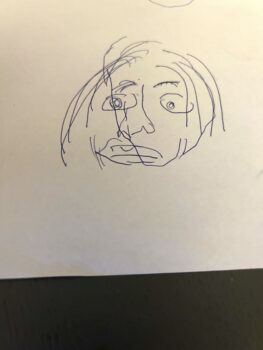

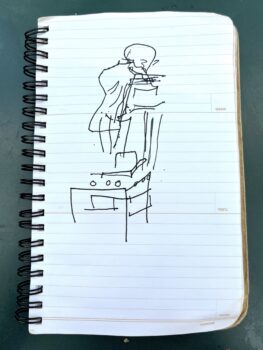

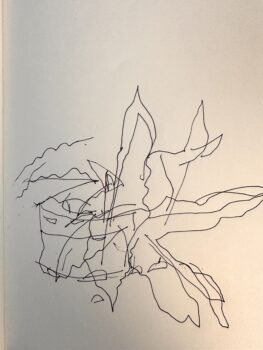

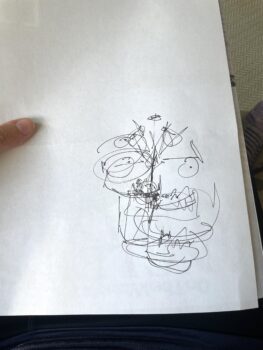

MACNAUGHTON: Can I give you, like, a formal assignment? One of my favorite things that I like to do — and I guarantee you, it will produce a terrible drawing, so let’s just take that off the table — is set a timer for three minutes. Okay? And choose an object or a person. It can be either, but let’s just start with, I don’t know, like a lamp. Look at your lamp. You’re going to draw that lamp for three minutes with one rule. You’re never going to look down at the paper on which you’re drawing. You’re going to draw the lamp without looking down. What happens is it takes the pressure off of the expectation that a lamp is supposed to look like this thing you’re looking at, right? And it brings you into your body and you start to notice all the details about the lamp that you don’t usually see. So, everybody’s homework is to draw either a thing or a person for three minutes without looking down, and I cannot wait to see what it looks like and how you feel afterwards. I guarantee it’ll look ridiculous. Okay?

The PIMA team’s 3-min drawings assigned by Wendy MacNaughton. From L to R: Steve Levitt’s (lamp and his wife), Lyric Bowditch’s (statue in a park), Morgan Levey’s (house plant), Jasmin Klinger’s (house plant).

We’ll be right back with more of my conversation with artist Wendy MacNaughton after this short break.

* * *

LEVITT: Going back to your book, How to Say Goodbye, I have to admit, the first time I opened it, I was in completely the wrong frame of mind. I was under a little bit of deadline pressure. I was in work mode. “Okay, let me pick up this book, let me extract the information from it, and get on to the next thing.” And fortunately for me, there’s a forward by B.J. Miller, who is a doctor who focuses on dying, who was a guest on the show, one of my most cherished episodes and one of my favorite people on the planet. B.J. sprinkles magic and joy on everything he touches. And the forward to your book is a great example. I’ve read it now three or four times, and every time it relaxes me, it slows me down, it makes me smile, sometimes it makes me cry. And he says one thing in particular that sticks with me. He says: dying is difficult, but in his experience, it’s harder for the people who are at the bedside observing the death than it is for the person actually dying. I mean, you saw a lot of people dying. Was that your take on the situation as well?

MACNAUGHTON: Yeah. When we’re at the end of our lives, there’s a lot going on inside, I’m sure, that we don’t really have access to. But the body’s going to do what the body’s going to do. And all of the family, friends, and us around the bedside, we are carrying a lot of expectations. We’re carrying a lot of fear and we’re putting that on the person. Something that B.J. speaks about so beautifully was letting go of those expectations and just being present with that person in the moment that they’re in. I think that’s part of our challenge, you know, at the bedside in those moments — and also in our day-to-day life — is just letting go of those expectations and really being present with all of the senses that we’re experiencing with a person who’s in front of us and just being there with them. It’s like time stops, and to sit in that space is hard — for me, at least. So, maybe that’s why, like, it’s a practice. Some people are practicing for their death, and also maybe some of us are practicing to be present with people.

LEVITT: I had the music producer Rick Rubin on the show and he said one of the most difficult parts of the creative process is the stripping away. And I have to say, your book is maybe the best example I’ve ever seen of stripping away because there really aren’t very many words; and what is left, I think by virtue of that, is super powerful. I mean, I’ve read the book now over and over and it’s, at least for me, impossible to read the book without being deeply moved.

MACNAUGHTON: I’m happy to hear you say that. To describe it physically, all the words are handwritten and sometimes there’s just four words on a page. And the drawings, they’re watercolor and pen drawings that were done from life, meaning that I was in the room with a person drawing who was in front of me. And they’re done with a lot of white space because I was trying to focus closely on that person and on that moment and arrange it in such a way for myself and for you who’s looking at it so that you can really pay attention to that person. The details of the way they’re sitting in a chair and their shoulder might be falling slightly and the way their sweater is hanging down — to me, there’s a whole story in that. It’s a picture of a moment and a feeling of a person at that time. And I tried to help the reader focus on that. So that’s why I said it’s like a poem, in a way. There’s a lot of intentional pacing to it, and I’m hoping that book will slow us down so that you enter a space of presence. You’re not trying to, like, get to the end and get the answer. You know what I mean? There’s no answer, folks. And the irony of this book — I think it’s kind of funny. It’s called How to Say Goodbye. I’d grab it off the shelf and be like, “Oh, it’s going to tell me how to do this thing.” But then the first thing you learn is there’s no right way to do this. There’s no one way to say goodbye.

LEVITT: There’s no one right way, but there is actually incredibly valuable, practical advice in the book. Much more so than I expected. I expected it to be a poem. I didn’t expect to have the urge, which I’ve fought, to actually take notes. So, the first piece of advice is: let the person lead the conversation, follow their lead. And it’s interesting because not two or three days before I first opened your book, I was having a conversation with someone who had just been with someone dying and another person in the room repeatedly tried to include that person in the conversation in ways that were incredibly awkward. Every once in a while, the person who was dying would say, “Peter, that’s you. Peter, it’s so good to see you.” And then maybe 20 minutes later would do the same thing. That was the level at which this person’s brain was operating. And yet, another person in the room kept on saying, “Hey, what did you think of what happened in the Super Bowl?” Or whatever it was. And I think it was just completely misguided, a complete mistake. I suppose that’s partly what you mean by follow the lead of the person who’s dying.

MACNAUGHTON: So, I’m trained as a social worker and there’s this principle in social work of: meet the client where they’re at. And that can be really hard to do when we enter a relationship and we want something out of it. And it sounds like your friend just wanted to connect with that other person on the way that they’ve always connected with them. But when we’re meeting somebody — whether it be somebody who’s dying, somebody who has, like, a cognitive impairment or something like that — if we want to be present with that person, we’ve got to meet them where they’re at. And that means slowing down and taking our expectations out of the way: sitting, listening, and being together.

LEVITT: The second piece of advice you have is: if you don’t know what to say, say, “I don’t know what to say,” which I think one level seems obvious, but I would’ve never done it absent you giving me permission to do it.

MACNAUGHTON: So, let’s explore that. What do you think the vulnerability is in saying that?

LEVITT: You know, I have to confess, I’ve never exactly been around someone who’s dying. I had a sister who died, but she was very much alive the last time I talked to her and really not present after that. My own misguided inclination would be to pretend that things aren’t so bad. And I feel like saying, “Oh, I don’t know what to say,” is an admission that things are really, really bad.

MACNAUGHTON: Yeah, it’s scary. I’m no expert in this either, and I think that’s part of saying, “I don’t know what to say,” is, I don’t know what to do and I don’t know how to be, and I can’t take care of you. I can’t physically do anything or say anything that will, like, fix this.”

LEVITT: It’s interesting because in the book that Stephen Dubner and I wrote called Think Like a Freak, one of the things we say is: “Nobody ever in a business context says, ‘I don’t know.’ Everyone always masquerades and pretends.” And I very much have abandoned the need to be an expert in that space. But having never been there as someone died, it’s interesting that my natural inclination is not to go to that same vulnerable place, which I so easily get to in a lower-stakes context.

MACNAUGHTON: You’re making me think of a conversation I had with somebody recently who is sick and told me they were scared. And I wanted to take care of them and I wanted to make them feel better, but I took a deep breath and opened up my heart and said, “I’m scared, too.” And then we held hands and it opened up this space of connection. And sorry to, like, go big here, but what are we here for if not that, right? That’s it, that’s the point. And maybe when we say we don’t know and the other person doesn’t know either, we can ‘not know’ together.

LEVITT: Another point you make is that it’s okay to be silent. And that, again, makes perfect sense once you say it. I can also imagine the desire to fill the air. I mean, humans in general have that deep desire to fill the air with noise. The silence, I assume, is hard.

MACNAUGHTON: I mean, I think we’re there all the time in our lives, constantly. In every conversation, we’re always trying to make connection through filling in space. I do this workshop where I teach a listening technique and a lot of it has to do with resisting the impulse to make everything that you say about me. It, like, actually takes hard work not to do that. If you say, “It’s hot here,” I say, “Oh my gosh. And it’s hot here, too,” right? Because I’m just trying to make a connection with you and trying to find something in common. But that’s a really different experience than sitting and being present with somebody, right? If you tell me it’s hot where you are and I’m just sitting being present with you, I want to hear more about how that feels for you. Is it muggy? Do you need to open a window? Like, it’s a different experience. And so that quiet space I think leaves opportunity for somebody to step forward who might not, and also just to not always be using our heads to fill in this space, to be using our other senses and our hearts.

LEVITT: The last one is: “Cry. Cry a lot.” And I was just curious whether you meant that on your own or with the person who’s dying — or both.

MACNAUGHTON: I don’t know if there’s a right answer to that. Some people cry alone. Some people cry in groups. Some people cry at Kodak commercials. Everybody’s a different kind of crier. But I think what is important is crying. It moves our emotions through our bodies. I’ve been crying a lot lately, to tell you the truth. I’m like, in a crying phase. And, boy, when I enter a big cry, I think, “This is it. This is my last cry. I’m going to die in the middle of this crying. This is too much. I can’t take it.” And then on the other end of that, woo boy, does that feel helpful. And then you start all over again the next day. But you know, the words — this is a very important point. The words aren’t mine. The words in there, these words are literally the words of hospice caregivers. I interviewed hospice nurses who are working at Zen Hospice, social workers. I spoke with people and I wrote down everything they said verbatim; and put it together into something that aligns with what I deeply heard from people. And so that’s what you’re reading. You’re reading kind of my reshaping of the wisdom that I heard directly from the mouths of people who have an incredible amount of experience and wisdom.

LEVITT: So, separate from the practical advice, you talk about something called “The Five Things,” and I was surprised I had never heard this before. Could you just say what the Five Things are?

MACNAUGHTON: The Five Things are: I forgive you. Please forgive me. Thank you. I love you. And goodbye. So these are five things I learned from somebody named Roy who was working at the guest house. And he explained to me that these have been used across many cultures in different forms for a really long time as these things that we can say to fully say goodbye to somebody so that there’s nothing that’s left unsaid.

LEVITT: I was so moved reading the book. I can’t imagine the process of creating it — how hard that must have been for you. You’re obviously an empath and this couldn’t have been easy to put together.

MACNAUGHTON: You’re getting to me, man. I have so many different kinds of work I do. It’s always drawing to connect with folks, but this was a toughie. I’ve drawn in some tough situations. I’ve drawn in Guantanamo Bay, you know, it’s been hard, but this one — so personal. We answer our own questions and keep asking them, I guess, with our work. Maybe that’s what you do. And maybe that’s our overlap between economics and art perhaps. But yeah, can you tell that it’s a personal project?

LEVITT: It must have forced you to think about your own mortality, your own death. Do you have thoughts about that?

MACNAUGHTON: It’s not something I don’t want to think about anymore. It’s not something I want to put off. It’s actually something that I am trying more and more to embrace. I’m still scared of things, and I’m still worried and sad, and all of those feelings, they don’t go away. But along with that, I think by being more cognisant and thoughtful about my impending death, I am living my days fully in a way that I didn’t before. This is the first public conversation I’ve had about this, like, in any real way. And it’s so meaningful to me, this book, and to go from something that’s private to public is — I don’t know if you’ve done a project that you never thought you’d share with the world, but thank you for being so sensitive to it. And careful with it.

LEVITT: Yeah, of course. I feel really lucky to be the first one to get to talk to you. Feels really amazing to be able to see the rawness and to feel the authenticity behind it.

MACNAUGHTON: Yeah, I don’t have any talking points yet.

LEVITT: There’s nothing worse than talking about a hard issue with someone who’s talked about it so many times that they’ve forgotten it’s a hard issue. I don’t know, I feel really, really lucky that we’re having this conversation. So, thank you.

MACNAUGHTON: That I’m so ungraceful right now? That I’m so unschooled? Thanks for being generous, and you’re a wonderful person to talk with.

LEVITT: If I understand correctly, after you graduated from college, you went to Rwanda. Is that correct? And what brought you to Rwanda?

MACNAUGHTON: Oh, that’s a deep cut. We’re going back. Yeah, I was working in advertising after I got into art school. And I was miserable, to tell you the truth.

LEVITT: I am not surprised. You seem like someone who would have enough sense not to go into advertising. How did that happen?

MACNAUGHTON: I went into advertising because I was frustrated with the whole art world and that the goal seemed to be to make stuff that you hang on a wall and 12 people end up seeing. That didn’t make any sense to me at all. Whereas advertising, if you make something and it goes on a billboard, everybody sees it, so imagine the kind of conversations you could start on a billboard. I learned quickly from my creative director that the point in advertising is not to make people think. It’s, in fact, to stop them from thinking. So I was not a good fit. Let’s put it that way.

LEVITT: How long did you last in advertising?

MACNAUGHTON: I think two years with a big chunk of time off when a friend of mine who was working as an election observer for the first free and fair democratic elections in Rwanda — this was in 1999, I’m dating myself — called kind of out of the blue and said, “Hey, you’re a drawer. And also you know how to create campaigns. And U.S.A.I.D. needs an educational campaign to sensitize the population of Rwanda to how to vote, how to use a secret ballot, why it’s good to vote, all this kind of stuff.” You hear this kind of, like, affect in my voice because at the time I didn’t know anything. I was a baby. Looking back, I’m like, my God, there was so much wrong with this. I’m the last person who should have been going and doing this, okay? But I was like, what, 22, 23, something like that? Young and dumb enough to, like, think I could do it, which is a gift of youth. And I said, “Heck yeah, I’ll go.” Got a leave of absence and went and found myself in a place I’d never been with people who I’d never met, creating an educational campaign for the country about how to use a secret ballot.

LEVITT: So this is in this shadow of a genocide that had occurred only five or six years earlier. The challenges to doing this must have been immense — or doing it well, at least.

MACNAUGHTON: Yeah, again, it’s so good I didn’t know because I never would’ve done it. And I’m very grateful that I had the experience. There were so many challenges. The whole thing had to be in drawings for two reasons. One is because, at the time, literacy was a really big issue in the country. About half the population was non- or semi-literate. And so everything had to be drawn. And also because of not wanting to identify people as being Hutu or Tutsi or Twa, which are the different ethnic groups in the area. And we were so close to the genocide back then, one could use drawings to make a generalization of a person without any kind of, like, features or anything like that in there. So, drawing does all these things that you can’t do with a photo.

LEVITT: Photos were banned.

MACNAUGHTON: Well you couldn’t use a photo in this campaign because it would be, like, a person as opposed to a generalized person. We ended up creating a huge campaign of, like, posters and smuggled spray paint in from the Congo. I don’t even know if I should be saying this. We, like, got these orphan kids, they’re called mayibobo, who were the orphan kids of the genocide and taught them how to use the spray paint and use stencils and go all over. And there was no graffiti at the time. So, they’re putting it on that side of the building. It was amazing. And it was a big success.

LEVITT: As I think about the 22-year-old you in Rwanda, and I think about the students I teach at the University of Chicago, one thing I have felt more and more is that the things that we’re teaching the students in the university are utterly useless for the tests they’ll actually have to face. And it sounds to me like going to Rwanda was a crash course in real life, probably in so many different dimensions you haven’t even talked about. And probably few experiences people have could match it because not only were you put into a different culture. You faced really hard problems.

MACNAUGHTON: With really high stakes. You know, talking about learning in public in real time, and there was real ramifications to this. I learned how to defer real fast. I learned that I wasn’t an expert real fast. But also, I learned how to build something, how to make something, how to have an idea, and then take it through every step of the way, how to collaborate with people, how to manage. All this stuff. I talked to some students just a couple days ago and they were talking about going to graduate school and then what kind of job they wanted and finding the right job that’s, like, exactly what they’re interested in versus their best skillset. And I was like, no, that’s the wrong job for you. You want a job where you don’t know what you’re doing. You’re completely in the deep end and you end up quitting in six months because that means that you just had a crash course. You just learned so much in all these areas and that you don’t think you’re going to use right now, but I think we all know in retrospect as we move on in our lives — my mom says this thing that I used to roll my eyes at all the time. She said, “When you go through life, you carry a basket and each of your experiences, you put into your basket.” I’m like, “Mom, that’s the dumbest thing.” And now I look, and I’m like, “Thank goodness I had all of these experiences,” because I’m constantly pulling from this now ginormous, oddly shaped, well-worn basket, to apply to the different circumstances that I go into with my work now.

LEVITT: Okay, so, let’s continue the list of places that you’ve spent time at. The next one that comes to mind is Guantanamo Bay, where you were drawing the trials of the detainees who were held there. How did that come to be, and what was that like?

MACNAUGHTON: Carol Rosenberg, who is the journalist who’s been reporting on Guantanamo Bay for The New York Times and another paper basically since before day one at Guantanamo Bay, she had an idea for a story about kind of the culture of the courtroom. And there are no photographs allowed in Guantanamo Bay. Everything that’s been documented, especially in the courtroom, is done through drawings. And The New York Times hadn’t sent somebody to draw there before. There’d been courtroom artists, but nobody who’d gone there on assignment to document. And so I went there to work with Carol and spent a week in Guantanamo Bay in the courtroom, drawing basically everything — not everything, because it turns out there’s a lot of things you’re not allowed to document there. And that was a big challenge.

LEVITT: Are you allowed to say the things you’re not allowed to document or is that classified?

MACNAUGHTON: I don’t really want to take that risk with you right now. Sorry. That, I mean — I think you’re great and this is an incredible podcast, but not worth going to jail over.

LEVITT: I’ll say it instead of you. So, I would imagine it’s things like where doors or windows are located. The fear is that some kind of attack will happen and by using your drawings, the people who attack the courtroom will find a weakness or something, I imagine. I’m just trying to think what the logic might even be other than that.

MACNAUGHTON: I imagine that could be true. Redact, redact, redact. I’ll tell you, I was so nervous about going. Totally unlike Rwanda, I was very well prepared. I knew a lot about that place, you know, enough to be nervous. And also I still felt an incredible sense of responsibility.

LEVITT: Why were you nervous? A sense of fear of safety or fear that it would be too much?

MACNAUGHTON: I had never been there. I didn’t know what it was going to be like emotionally. This is a terrible place. Like, there’s an emotional weight that’s there. And there’s no edit button on a drawing. There’s no “delete.” There’s no do-overs. You just have the time you have and you get what you get. And I wanted to do a good job. So I wanted to practice a lot. I went to some courtrooms here in San Francisco just to get the idea of different angles and how people moved about. And then when I got there — I mean, this is what it always is. It doesn’t matter if it’s Rwanda, Guantanamo Bay, or a street corner somewhere. Once you actually get on site and you’re doing something, everything goes out the window. There’s a million more challenges you could never anticipate. So, there was certain things I couldn’t draw. I had to have my paints kind of on a folding chair off to my side, and I had a tiny cup of water. And at the end of each day, everybody — all the viewers, who were like journalists and N.G.O.s — would leave the viewing room and then a communications officer would come and sit with me and go through my drawings and make sure that I hadn’t drawn anything that I wasn’t supposed to. And then they would put a stamp of approval with a signature on my drawing that says, “This has been approved and it cannot be altered after this. No change is allowed.” So, even though I draw from life, I am used to being able to, like, crop something out or change a little something here and there, you know what I mean? I mean, this is going in the Times, so I want it to be accurate and be good. And it just was what it was.

LEVITT: One of the stories I’ve heard you tell is how — Mr. Lavender, you said, was the name of the person who was giving you those stamps. And at the end, I think you said to him with sort of joy and a sense of sharing that because his stamps were such a part of this picture, that he was a co-creator. And I think he wasn’t very amused by that.

MACNAUGHTON: I mean, come on. This man was not amused by much. You know, you sit with somebody at the end of every day and look at this artwork together. You get to know them, you become friendly. So this gentleman, I called him Mr. Lavender — I thanked him because those stickers are such a part of the artwork. It literally couldn’t exist without that sticker on it. So, I thanked him for being a collaborator on this. And I do not think he was too happy or amused about it.

LEVITT: He didn’t want an art credit in The New York Times, apparently. He could have added that to his resume.

MACNAUGHTON: I don’t know. There wasn’t much art or creativity or senses of humor going on around that place, I will say.

LEVITT: You described it as a terrible place. In what ways was it terrible?

MACNAUGHTON: I was not expecting it to feel so bleak and run down and ill kept and tucked away and steel and metal and rust and hard and inhuman. It’s very inhuman. One of the hardest, terrible things for me about it was the drawing. When I was given my rules of what I could and couldn’t draw, another rule was that I was not allowed to make eye contact with the people that I was drawing on the other side of this glass that’s separating the viewer room from the courtroom. And in particular, the detainees. And this is very complicated. I mean, as an artist and as a human being, the foundation of everything is eye contact. That’s how we connect as humans and as I’m drawing somebody. I’m not a camera, I’m a drawer. And it is about humanizing, not dehumanizing, no matter who it is. And so, to be told that if I were looking at somebody and they looked back at me, I was to look right through them. Just keep looking and look through them. That is too much for this person. It’s not my area. When I left I did not want to go back, because it undermined my entire purpose of drawing. I’m so honored that I was able to go and do the job, and I think I did it well. And I think I did a service to the newspaper and to the readers. But that’s not what I do. I can’t put myself aside. I think I’m my best tool, and I had to put that away.

LEVITT: Within a few days of getting into Guantanamo, you started smoking? Is that true?

MACNAUGHTON: No! Sorry. I just, like, realized my parents might listen to this. Yeah, I totally did. I was a smoker for so many years and I was — oh boy, yes, I started smoking again.

LEVITT: How long had it been since you had smoked and then —

MACNAUGHTON: Why are we talking about this?

LEVITT: What I find interesting about this is that it brings home how hard this would be. I mean, because honestly — you and I are very different people — and this doesn’t sound hard to me at all. The logistics of how you draw and doing it well might be hard, but the human part of it, to me, doesn’t seem like it would be that hard. I’m not that connected to people anyway. I hardly ever look anybody in the eye in the first place.

MACNAUGHTON: So, there’s a little bit more context for the challenge of it. I would be surprised if it wouldn’t be challenging for you because in the viewer room, not only was there journalists and N.G.O.s, but there was also family members of the victims from 9/11. And on the other side there were the detainees, who have been accused of orchestrating and perpetrating that. And so, sitting in the middle of that — and the role of a journalist in this is to really not have any kind of emotional response, not to make the eye contact, not to create the relationships with anybody, because that’s a vulnerability to really having objective truth-telling. This is why I say I am not a journalist. I use the term “drawn journalism,” for lack of a better term. But I don’t have that skill. Do you think in that situation that you’d be able to just — I don’t even know, I don’t want to say turn off, but you know what I’m saying? Just do the job?

LEVITT: Yeah, I’m mostly turned off anyways. I think it wouldn’t be that bad for me. I’m unfortunately not very empathic and I’m detached. So, who knows? But going to Rwanda, that sounds hard to me. Being in the Zen Hospice Center, that sounds hard to me. Of those three things, Guantanamo Bay seems like a piece of cake.

MACNAUGHTON: That’s so interesting. I think that I went into both Rwanda and the Zen Hospice experiences with less expectations. And in Guantanamo Bay, I had a lot of expectations. The effect that had on my work, I don’t know. It certainly had a lot of effect on my mental health.

You’re listening to People I (Mostly) Admire with Steve Levitt and his conversation with artist Wendy MacNaughton. After this short break, they’ll return to talk about how to have fun.

* * *

In the last part of our conversation, I’m going to ask for Wendy MacNaughton’s help on what has been a frustratingly difficult task for me: my ongoing quest to relearn how to have fun.

LEVITT: Despite the fact that you choose to spend your time in places other people would avoid, you also put a lot of emphasis on fun.

MACNAUGHTON: I know. I was going to say, you’re making me out to be this, like, very serious person.

LEVITT: You’ve written about the fact that we as a society have forgotten how to have fun. Can you riff on that for a little bit?

MACNAUGHTON: I did a lot of different books that are all about having fun, whether it be in the kitchen or the outdoors or whatever. I’ve drawn a lot about it and also did a piece in The New York Times called “How to Have Fun Again.” I don’t know where you’re at with this, but there was this time when we were coming out of the pandemic — and we still are in a lot of ways — and there’s just kind of a heaviness. And we’re not putting ourselves in places and in spaces to like be kind of spontaneously creative or have super present moments. And I certainly was in that space. I was kind of down. And I was visiting a friend in Oregon and we were the top of a hill and it was covered in grass and, like, something came over me and I’m like, “Can you hold my stuff?” And then I just dropped down on the ground and I rolled. Just — like, I rolled like a six year old, you know, like all the way down and screamed and laughed and almost threw up. And it was the best antidepressant ever. It was like all of a sudden I just felt so in the moment and so happy and so joyful and I realized, my God, when’s the last time I had fun? So I did a little deep dive and asked a bunch of people about how they have fun and then did a piece encouraging folks to do it because it is pretty healthy.

LEVITT: So, roughly every three months I make a pledge to myself to try to have more fun.

MACNAUGHTON: Really?

LEVITT: Yeah. And it came out of some episodes I did here. And what I’ve come to realize is that I am almost completely incapable of playful fun. And so my latest iteration — I set the bar so low. For about the last week, each night when I climb into bed, I ask myself, “Did I have one episode today where I had playful, joyful, fun?” And more days than not, the answer is no, even though I’m trying and I’m seeking. For so long I have put an enormous emphasis on investment in the future. So in academics, there’s so many projects to do. There was always a sense that I should be working on these things towards a long-term goal. So then, to offset that, I would get hobbies, but I found I was incapable of just having fun with a hobby. As soon as I get into a hobby, I start scheming about, “Okay, wait, now I play golf. Wait, I shouldn’t just play golf. I should try to be on the professional golf tour at 50.”

MACNAUGHTON: Masters, right?

LEVITT: Yeah, exactly. And I cannot in myself unlock the ability to go back to childlike fun. I try and, I don’t know. I need some advice. Do you have some advice?

MACNAUGHTON: I love this. We can share a list of all the ways that you’ve found and that I’ve found. Rolling down a hill. Fantastic. Rope swings are great. For me, that always has to do with laughter, almost always. Being outside really helps and being around other people is key. I mean, I can make myself laugh, don’t get me wrong. I can tell myself a mean joke and I think I’m hilarious, but when I’m laughing with a group, that’s like what gets my endorphins or whatever. Now, let me just say also, I think having a conversation about deconstructing fun does not fall on the list. So, I thought it was kind of, like, hilarious that there’s this piece out there instructing people, “This is how you need to have fun.”

LEVITT: Can I tell you the irony I saw in that piece? It was clear from the message that social media was not fun, right? And yet the piece ended with your call for people to post on Instagram with hashtag: “NYTOpinionFun.” And I wondered — you must have thought about that — was that forced upon you or did you willingly go in that direction?

MACNAUGHTON: No, I just — I can only be who I am in all my imperfection. I think there’s always an opportunity for community building in social media. There’s a lot of irony there, and I don’t know if that came from me or the paper or what, but it’s pretty silly.

LEVITT: Social media is the whipping boy for everybody now and everything bad, but the flip side is that social media and technology have opened up enormous opportunities. So you teach tens of thousands of people to draw online. You’d never be able to do anything like that in a lifetime without it. Our conversation, so many people will get to listen to it because of that. It’s a change in society that has profound implications. And it’s interesting because I think this is one where both artists and economists have a really deep well in which to dig to try to make sense of it.

MACNAUGHTON: Yeah, I’m interested in hearing your take on it. Like, what’s your hot take on social media?

LEVITT: So, I’m not a big consumer of social media myself, but what I will say is when I do go on social media, it is amazing the quality of what you find there in terms of entertainment. The fun and the creativity is remarkable. And no economist would’ve ever imagined that you could have a technology where you would mostly pay nobody anything to produce enormous amounts of content that are out there.

MACNAUGHTON: Yeah, that makes no sense to an economist, huh?

LEVITT: Yeah. On the other hand, my friend Sendhil Mullainathan, who’s an economist and one of the smartest people I know, he deeply believes that boredom is the key to everything. And my kids have never experienced that. My kids don’t have a moment where they’re alone or bored. They are constantly connected and they never have to face the scariness that is being by yourself. And I suspect that has profound implications on development and what life will be like for my children and people beyond.

MACNAUGHTON: I would agree. I think it’s the upside for me of being an only child I had a lot of space and time to play games and make up stories on my own and create things. And I find personally now, many years later, that I do want to fill space. And social media is a great way to do that. And I have never come up with a good idea while looking at social media. Ever. I do not leave that experience having created anything or grown. I can take something from that and then go off somewhere and have some space and be bored and that’s when some ideas might come up related to that experience. Another irony, like you mentioned, I’m teaching kids and now grownups, too, about drawing and I’m using social media to do it, whether it be on YouTube or like a — I do something called “The Grownups Table” on Substack and do drawing lessons there. So it’s dependent on social media for communication, but then what I hope I’m doing is I’m teaching people tools there and giving them the experience to hook ’em, Like, they can practice on their own and they can build that muscle independent of social media. And in my experience, if somebody does that on their own enough, the benefit that they get there outweighs the benefit that they get on social media. It’s longer lasting, it’s deeper, it creates community. And those are the things that ultimately we’re looking for on social media, but we don’t get, right?

LEVITT: So, it’s probably an illusion, as I talked to you and as I’ve read about you, that when you plot your path forward, you don’t seem very concerned either about whether the things you’re doing will take a lot of time, or whether they’ll earn you any money. You somehow seem immune to these two forces which drag everybody down. Is that true? Do you somehow operate in a world in which those two things don’t act as constraints on what you do?

MACNAUGHTON: I can’t believe you’re asking me that. Like, that’s so funny. I don’t think anybody’s ever really put such a fine point on it before, except for my therapist. Other parts of my life would be a lot easier if I cared more about efficiency or about making a good profit. That’s not what excites me, and that’s not where my talents lie. I’ve said often, if you want to make a lot of money, don’t hire me. Don’t come talk to me. But if you want to make a big difference, let’s chat. I have, like, a weird — what are these called?

LEVITT: Antennae.

MACNAUGHTON: Yes. I have a weird antenna. I’m a good responder to being, like, of service or useful and using drawing to be of service or useful in situations. I feel like, “Oh, this is this thing I have to do in this moment.” And for better or worse, I don’t really say, “But you have more responsible things to do.” I don’t know how to do that. I do the thing that I feel I’m drawn to do, you know? I tried once to make a little matrix, like, when I was first starting drawing — when I said, “This is going to be my job.” And I quit my job, and I drew full time — I made this little matrix of like, in order for me to say yes to a job, it has to check like the purpose box, the money box, the will-this-take-me-forward-in-my-career box, and, “is it fun?” or something like that. And I think it quickly became like, does this feel right purposefully and is it fun? — and the other two have disappeared. And while it might not take me to having a summer house or something like that, that’s okay. I get a lot better stuff out of my work than that.

LEVITT: It seems like it’s taking you somewhere better. You have joy, you’re fun, you enjoy your life in a way that most people don’t. I mean it’s interesting because even though we’re far away, we’re doing this, you know, remotely, in my own self, I feel this lightness and this joy that is just — is wonderful. I laughed more with you today than I laugh usually in a week.

MACNAUGHTON: So, you can — tonight, like, you can check this off.

LEVITT: Oh yeah, when I lie in bed tonight and say, “Today I had some fun.”

Well, if that was like to talk to artists, I should definitely not wait another 25 years to talk to the next artist. I did take Wendy up on her drawing challenge to draw objects without looking at the paper. You can find the drawings I made on our website, freakonomics.com in the blog post for this episode. You can judge for yourself, but I stand by my claim that I am no artist. The worst part isn’t how badly these drawings turned out; it’s that I actually wouldn’t have done much better if I were allowed to look at the paper. And if you’re interested, check out Wendy’s book, How to Say Goodbye. It really is very, very special. A book I will always cherish.

LEVITT: So as always, this is the time in the show where we take a listener question and I invite Morgan, our producer, to come and talk with me about it.

LEVEY: Hi, Steve. So a listener named Elly wrote in with a question about quitting. In the fall, we had former professional poker player and quitting advocate, Annie Duke, on the show. And you both feel that people should quit things more often and earlier. The listener, Elly, wants to know if the ability to quit, particularly jobs, is a luxury? To walk away from a job often involves a financial safety net. So how do you think privilege factors into the quitting conversation?

LEVITT: So I think there’s a lot of truth to what Elly said — that quitting, like many things, in life is a luxury. But I do want to say one thing just to make sure that people understand my position on quitting, because I think it’s easy to confuse about what I’m saying and what I’m not saying when I talk about quitting. So when I talk about quitting, I have a really simple spiel: That I believe, based on my own experimental data and on a big body of psychology and behavioral economics, that people have a bias against quitting. So if you find yourself in a situation where you’re really indifferent, where you’re waffling back and forth, you just can’t decide what to do, I believe in that particular instance, quitting is the right thing to do. Okay. And that would apply to anyone. Anyone, privileged or unprivileged, who finds himself in that position, they should quit.

LEVEY: So what you’re saying is when the option to quit is on the table — obviously some people don’t have the option to quit their job, but if the option to quit is on the table, and people are waffling, they should quit in your opinion.

LEVITT: My view is that people know better than anyone else what’s right for them. If you are actively debating quitting your job, it means that you can see another path that is about as good as staying with your job. And in that case, you should probably quit. But look what I’m not saying is if you have a job you hate. You should quit it because really you shouldn’t quit the job you hate if you’re going to lose your house and live in a car and living in your car is worse than doing the job you hate. Quitting is all about options and privilege and luxury comes with greater options. So the point I really want to emphasize is: somebody who wasn’t listening carefully to what I’m saying, could take away the wrong rule, which is quit when you’re unhappy. And that’s not my rule at all. My rule is when you really can’t decide whether to quit or not, then you should quit. And that’s a really important distinction to make and it’s totally in line with Elly’s very relevant observation.

LEVEY: Steve, when I decided to ask you this question, I was a little worried that your answer was going to offend all of our listeners, and I’m pleasantly surprised that it didn’t.

LEVITT: You misunderstand me, Morgan. I’m not offensive by design. I’m just offensive when the things I believe don’t line up with the things that other people believe. And sometimes I actually do think about the world the same way other people do and I guess this is one of those.

LEVEY: Elly, thanks so much for writing in. If you have a question for us, our email is pima@freakonomics.com. That’s P-I-M-A@freakonomics.com. We read every email that’s sent and we look forward to reading yours.

We will be back in two weeks with Obi Felton. She used to be in charge of early stage moonshots at Google X, and now she’s got a startup that’s trying to address the youth mental health crisis.

* * *

People I (Mostly) Admire is part of the Freakonomics Radio Network, which also includes Freakonomics Radio, No Stupid Questions, and The Economics of Everyday Things. All our shows are produced by Stitcher and Renbud Radio. This episode was produced by Morgan Levey with help from Lyric Bowditch, and mixed by Jasmin Klinger. Our theme music was composed by Luis Guerra. We can be reached at pima@freakonomics.com, that’s P-I-M-A@freakonomics.com. Thanks for listening.

MACNAUGHTON: I think you are totally an empath. There’s no way that I could feel comfortable like I feel with you if you weren’t reflecting my feelings, too. So you’re wrong. Okay. Also, I hope that we have, for both of us, removed this barrier between the economist and the artist, right?

LEVITT: For me for sure.

MACNAUGHTON: For me, too. I’m actually still a little bit intimidated.

Sources

- Wendy MacNaughton, artist and graphic journalist.

Resources

- How to Say Goodbye, by Wendy MacNaughton (2023).

- “How to Have Fun Again,” by Wendy MacNaughton (The New York Times, 2022).

- “Inside America’s War Court: Clothing and Culture at Guantánamo Bay,” by Carol Rosenberg and Wendy MacNaughton (The New York Times, 2019).

- “Drawing the Guantánamo Bay War Court,” by Wendy MacNaughton (The New York Times, 2019).

- Think Like a Freak, by Steve Levitt and Stephen Dubner (2014).

- DrawTogether.

- The Grown-Ups Table.

- Zen Caregiving Project.

Extras

- “Rick Rubin on How to Make Something Great,” by People I (Mostly) Admire (2023).

- “Annie Duke Thinks You Should Quit,” by People I (Mostly) Admire (2022).

- “Does Death Have to Be a Death Sentence?” by People I (Mostly) Admire (2022).

- “Sendhil Mullainathan Explains How to Generate an Idea a Minute (Part 2),” by People I (Mostly) Admire (2021).

- “Sendhil Mullainathan Thinks Messing Around Is the Best Use of Your Time,” by People I (Mostly) Admire (2021).

Comments