Episode Transcript

Miki AGRAWAL: I’m in the business of taboo. My job is not to be afraid to talk about things.

Things like…

AGRAWAL: It absorbs at least two full tampons’ worth of blood, so you don’t have to change halfway through the day.

Things like…

AGRAWAL: If a bird poops in your face, would you take a piece of paper and wipe it with paper or would you wash it?

And things like …

AGRAWAL: The way I consider myself as a feminist is the fact that I’m solving a problem for women. If that’s not feminist I don’t know what is.

Our guest today on Freakonomics Radio …

AGRAWAL: My name is Miki Agrawal and I’m the C.E.O. and co-founder of THINX.

And what’s her advice to would-be fellow entrepreneurs?

AGRAWAL: I always ask them three questions to answer. Question number one is, “What sucks in my world?” And question number two, “Does it suck for a lot of people?” If it sucks for just you, then maybe you’re just a diva and go screw yourself. But if it sucks for a lot of people then it’s an opportunity. And question number three, which I think is the most important to ask yourself, is, “Can I be passionate about this issue, cause or community for a really long time?” Because it does take 10 years to be an overnight success.

* * *

Miki Agrawal, 38 years old, is an entrepreneur and a striver and, perhaps most of all, a disruptor. That’s just how her family does things.

AGRAWAL: My mother’s from Japan and my dad’s from India and I grew up in Montreal, Canada. And my parents met and fell in love in 1974 and it was an “all odds against them” love story. My dad had an arranged marriage for him set in India. His big dilemma was, “Do I marry for love or do I marry for duty?” ’Cause they had a dowry to give to their family, which would have helped out the family. My mom, she was Japanese from a very wealthy Japanese family. And to her parents’ utter shock and dismay, she was choosing to marry this Indian man who’s middle class from India. And her big dilemma was, “Do I marry for love or do I marry for honor?” And they both chose each other and within seven months they were married and then they had three children in one year.

One daughter and then, 11 months later, twin girls. Miki is one of the twins. Their father was an engineer; their mother had studied international relations.

AGRAWAL: My parents were real problem solvers. And they weren’t entrepreneurs, but they really were. I remember growing up, when I was in elementary school, my mom was looking for a gifted children’s summer camp for us. And there were sports camps and there was regular summer camps, but there wasn’t any gifted children’s summer camps. They decided that we’re going to start our own. Like, “This is lacking in the community, we’re just going to do it ourselves.” My mom, with her thick Japanese accent, without any connections, any money, any relationships at all, managed to build the first gifted children’s summer camp, and it ran for 15 years with 500 kids per year and it was super successful. And then when we were in high school, 14 years old, my parents recognized that electronics was going to be the future of the world. And at the time, there was no cell phones and computers were just beginning. My family had the first Commodore 64 computer in our family neighborhood. And my dad was an aeronautical engineer and believed that electronics was the future. But what they did was they decided that they wanted their kids to learn about electronics and they couldn’t find anywhere for their kids to learn about it. They decided to start their own company called Tomorrow’s Professionals, which is this electronics kits company that my dad wrote the manual, the experimenter’s manual and my mom built the little kits which had breadboards and resistors and transistors and diodes and LED lights and switches and speakers and alligator clips and all these different things that you can make: burglar alarms, and you can make switches that turn the light on, and you learned about electronics. And they ended up selling this company all over Canada and built a really cool educational business out of it. Throughout my life they just were seeing issues in the community, finding holes and rather than just complaining about it, they just did something about it. I observed my parents do that and therefore I was like, “Oh, I don’t have to have any resources, any money, any connections — if I see a problem I’m going to go solve it.”

Agrawal and her twin sister were eager to come to the States for college. They attended Cornell and played soccer.

AGRAWAL: I mean, I played my whole life. We practiced constantly and played at the highest level in Canada. But going to an American college where sports, especially Division 1, was taken extremely seriously. You have strength training, and then you have fitness, and then you have to go to your practice, and you have a 72 hour rule, so you can’t drink for 72 hours. Not that we drank much anyway, but it was a very strict process and I think that gave us a lot of discipline as well. And then after my senior year in college, we started thinking about jobs. And we didn’t really know what we wanted to be when we grew up because we were soccer players our whole lives. That’s what we defined ourselves as.

DUBNER: You keep saying “we” — it sounds like you and your twin sister. Radha is that her name, yes?

AGRAWAL: Yeah. We talk in “we’s” constantly. I don’t even know how to say I.

DUBNER: Are you or were you virtually inseparable? I mean it’s a little bit weird for twins to decide to go to the same school and do the same things.

AGRAWAL: Yeah, we were. I mean, we both were both recruited to play soccer at Cornell as a one-two punch and we both studied the same things and we just, yeah, we were pretty attached at the hip. We always had a buddy that no one ever messed with us. We always had a level of self-assuredness because we always had somebody laughing at our jokes and there to be there for us no matter what. So I talk in “we’s” because it’s always me and my sister. Yes, I suppose.

DUBNER : You went to college together, you played college soccer together, you moved to New York together. Then what?

AGRAWAL: Then I got a job investment banking at Deutsche Bank — “douche bank.” And I did the training for the investment banking analysts’ training program. And within two months, I officially started my job September 1st, 2001, and my subway stop every single morning was Two World Trade Center. I would get off at Two World Trade Center, go upstairs, get tea with my girlfriend who worked on the 100th floor of Two World Trade. And I would walk across the street to my office, which is directly across Two World Trade Center. And 9/11 happened and 700 people in my girlfriend’s office died on that day and two people in my office died. Crazy, crazy stories. I worked at 130 Liberty directly across Two World Trade Center.

Where was Agrawal that day?

AGRAWAL: I just slept through my alarm clock. I was supposed to be there at 8:30 in the morning and I just slept through my alarm clock and missed the whole thing. And I’ve never in my lifetime slept through my alarm clock except one single day. It was pretty remarkable, to be honest.

The communal tragedy jolted Agrawal into a personal revelation.

AGRAWAL: I recognized that truly the mystery of life is you never know when it’s going to end. The goal is to really make every moment count. And I was so lucky that I was 22 years old and not 32 or 42 when I had that realization, that “aha” moment, that I’m not going to pursue investment banking for money or status or to get, you know, I just absolutely know I’m going to do something that lights me up. I wrote down three things I wanted to do with my life and the first was to play soccer professionally. The second was to make movies. And the third was to start a business.

The New York Magic, a women’s soccer team, was holding tryouts in Brooklyn.

AGRAWAL: I just decided to try out, and I snuck out of my investment banking job for two and a half months straight.

The tryouts whittled down the many aspirants to a select few.

AGRAWAL: And then, I made the team and made the starting lineup and was all set to quit my investment banking job. But I decided, just in case, who knew what would happen, and I just decided to stay in my banking job and play my first game of the season. And within eight minutes of my professional career, after I assisted a goal, a girl came and slide tackled me and I heard that telltale snap and tore my ACL. I had to stay at the investment bank to get the very best health insurance and the very best physical therapy to rehabilitate myself and I came back out the following year with the starting lineup again, and then in a semifinal game in the next season I tore my other ACL.

By now, Agrawal had left banking – and now her soccer career was also over. Time for item number two on her list of career goals: making movies. During college, she’d had summer jobs in L.A. in the film business so she reconnected with her contacts and she got some entry-level work. After a while, she was helping to produce commercials and music videos. And then, one day at the craft services table – an epiphany.

AGRAWAL: When you’re eating out on set all the time, you’re eating crappy processed food — getting pigs in a blanket and processed candy and just crap. And I kept coming home with horrible stomach aches and finally I was like, “Enough is enough.” And I researched it and in my research discovered the huge processed food industry, all the crap that was in food. I was just like, “This is absurd.” I started looking at the foods that I had to give up, when my favorite comfort food was pizza. The pizza industry’s a $32 billion industry, and yet nobody was making it better for you. They were just adding more processed cheese, more processed toppings, bleached flour, sugar-filled sausage. It was just bad. My first ding-ding-ding idea was, “I’m going to create New York’s first gluten-free, farm-to-table pizza place.” And I had no experience.

Lack of experience had not stopped Agrawal’s parents from their various startups. She figured she’d figure it out. The smart thing, she thought, was to seek out people who knew the restaurant business.

AGRAWAL: I started by trying to do one-on-one meetings and trying to pick people’s brains and nobody wanted to meet with me and I was like, “This is so stupid.” And it would take forever. If I want to pick 20 people’s brains and I’d have 20 meetings and 20 cups of coffee and I don’t even drink coffee.

So she came up with a different plan. And she leaned on friends.

AGRAWAL: And so what I did was I borrowed my friend’s beautiful New York City loft apartment.

Another friend was a chef.

AGRAWAL: I remembered meeting playing soccer in Central Park. I found out he was a chef and I asked him to come and cook a meal for this event, and in exchange he’d be able to spend five minutes telling his story about his chefing experience, etc.

The event was a nice free meal in a beautiful apartment to which she invited 20 people who she thought could help her start her healthy-pizza restaurant. Business people, food people, creative people.

AGRAWAL: 20 out of 20 people showed up, and I’m like, “Oh my god, you need to meet this person, you guys will fall in love,” like, “Oh my god, you guys can talk about design and writing and work together,” and I made sure that everyone got something out of the experience.

Beforehand, by e-mail, Agrawal had asked everyone to think about the big questions she had about starting a restaurant.

AGRAWAL: And they get to now come and ideate about someone else’s business without having any worry about doing it or dealing with it. They get to come and just give their opinion and that’s it. I walked out with so much knowledge.

In 2006, she opened the restaurant, called Slice, on the Upper East Side. But she didn’t follow the advice she’d been given. Rather than doing a soft launch and working out the kinks quietly, she got a bunch of advance press, was overwhelmed by demand, and generally she had every sort of problem a new restaurant could possibly have. Eventually, she brought in a pro to run the place. In any case — now that she had experience starting a business, she was open to starting another one. All she needed was a killer idea.

AGRAWAL: And in 2005, my twin sister and I were at our family barbecue and we were defending our three-legged-race championship title — as one does.

If you haven’t deduced by now – Miki Agrawal is a little… um… competitive. She likes to win.

AGRAWAL: And in the middle of our three-legged race, my twin sister started her period. And we were tied to each other and we had to sprint to the finish line, still in first place, and ran up the stairs still tied to each other. Still tied to each other, ran to the bathroom. And in the bathroom, as my sister took out her bathing suit bottoms and was washing the blood out of the bathing suit bottoms, is when the idea hit. It was like, “Oh my gosh, wouldn’t it be amazing if we could create a pair of underwear that never leak, that never stain, that could just support women during really important times, like the three-legged race.” And then we went outside and talked to our older sister Yuri, the one who’s 11 months older, and she’s a head-and-neck surgeon at Johns Hopkins. I remember trying to borrow a pair of underwear from her one time and looked in her underwear drawer and every single one of her underwear was soiled. And I was like, “What is up with that?” And she’s like, “Well, in the middle of an operation you can’t just, when you’re operating on somebody’s face, you can’t just be like, “Yo face, stay open while I go and change my tampon.” You can’t do that. You have to finish the operation. You leak in your blues and you get, you leak everywhere.” She’s never had an option that supported her when she was in middle of a 12, 14 hour operation and then we thought about all the different scenarios: when you’re on a plane, or you’re stuck in traffic, when you’re giving a presentation, when you’re on a recital, when you’re doing anything. It was just like, “Oh my god, that is a huge, massive opportunity here where there hasn’t been innovation in 50 years, in this category, or more.”

DUBNER: Was no one else offering period panties at the time? Were you the first?

AGRAWAL: I mean, there had been some mom and pops who tried, but they were plastic diapers that nobody wanted to wear. For all intents and purposes, there was none that existed. What we wanted to do was create a pair of underwear that, not only did it look and feel like a regular pair of underwear — and by the way, the underwear category is a $14 billion category, so combined, underwear plus feminine hygiene is a $30-plus billion category that had very little innovation. Underwear was only being made more see through, more sexy, more flimsy, more lacy, more unsupportive for women and not only on your day of your period but you have discharge in mid-cycle, you have ovulation. I mean, these are things that happen to women. We want to create a product that made a woman feel like they were just putting on a beautiful, regular pair of underwear, that felt sexy, that looked great, that felt comfortable and actually worked. The innermost layer wicks away moisture keeping the user feeling dry. You don’t want to bleed into something and feel wet, you want to feel dry. When you have an overflow or leak into them, you don’t feel wet at all. It’s odorless because there’s anti-microbial technology that you don’t smell anything. It’s absorbent, it absorbs at least two full tampons worth of blood, so you don’t have to change halfway through the day. You last a whole day and you had to go home and just hand wash it, either hand dry it or throw it in the washing machine, comes out brand new. We had this idea. We spent three and a half years developing and patenting the technology to make sure it’s exactly what we wanted ourselves. And that’s what took us almost four years to develop the product. Now it was time to go out and raise money. And that was one of the greatest challenges of my life because, again, most investors I met were men.

DUBNER: So now you go out to meet with V.C.’s. And what’s that pitch like and how well — obviously it worked eventually. Did take a while, or no?

AGRAWAL: Oh my god, it took over a year, and initially you meet with so many people and it’s like, “Let me take this to my wife.” And I’m like, “Oh my god I hate you.” It’s out of context, and what are you going to say to your wife. They have no idea. And then they would come back like, “No thanks.” And it was just like, “Ugh.” And we would try everything and we’d be like, “You don’t understand how a woman feels on your period. It’s scary.” They didn’t care about that. Eventually I figured out the way to talk about it to men, which was really about the industry. “There’s a huge opportunity to disrupt and create this multibillion-dollar space that no one’s touched in 50 years.” And then eventually — we actually raised no money in the beginning. We tried everything and we didn’t raise any money, so we had to actually launch a Kickstarter campaign and we raised $65,000 on Kickstarter. Then we did an Indiegogo campaign, raised $20,000 on Indiegogo and then we did, we entered a couple of challenges. We won a contest, won a $25,000 cash purse and then we launched a crappy 1.0 pre-launch website and raised another $20,000 there. So altogether we cobbled $130,000 and used that money to produce our first 3,000 units in China. And then, and then we were able to take that 3,000 pairs of underwear and then send it out to our customers, our first pre-selling, preorder customers and then we sent out a survey thereafter and then got a bunch of feedback and used that survey to go out and raise an Angel round. We raised about $425,000 in our Angel round and then we subsequently closed a series A round with a strategic investment partner who now manufactures all of our products.

DUBNER: You’re up through series A now, or have you gone beyond A?

AGRAWAL: We’ve been profitable. We haven’t had to raise any more money.

DUBNER: Give me a little bit, as much as you’re willing to divulge, what THINX is worth at the moment and or what your annual revenues are.

AGRAWAL: I wish I can tell you that, but I really can’t. I can tell you that we grew 23x from 2015 to 2016 in revenue. That’s all I can say right now, because we’re…

DUBNER: And you’re profitable.

AGRAWAL: And we’re profitable. Yeah.

DUBNER: How many employees?

AGRAWAL: We are going to be pushing 40 in a few weeks. Yeah, 37 plus a few.

Coming up on Freakonomics Radio: the ad campaign for Agrawal’s period panties was a bit much for some people…

AGRAWAL: The fact that New York City subway system did not want to put our ads in the subway shows that we are wrapped in this patriarchal system right here in the most progressive city in the world, New York City.

And, once she got in the business of taboo, Miki Agrawal was eager to go further.

AGRAWAL: When you think about the way we go to the bathroom and poop, that literally hasn’t changed since 1890.

* * *

In 2014, Miki Agrawal, along with her twin sister Radha and a friend, Antonia Saint-Dunbar, launched a company called THINX, with an X. It makes “period panties,” to be worn instead of the standard menstrual items like pads or tampons. But to Agrawal, her period panties are different.

AGRAWAL: It’s not just buying a menstrual item.

To her, it represents more than that.

AGRAWAL: It represents freedom, it represents liberation, it represents, “Let’s talk about this. Let’s face this thing that people are considered that people consider taboo.”

A lot of inventors and entrepreneurs are driven by some origin story from their youth. Not so Miki Agrawal.

AGRAWAL: Honestly, I have zero recollection of getting my period for the first time. I was a very busy kid.

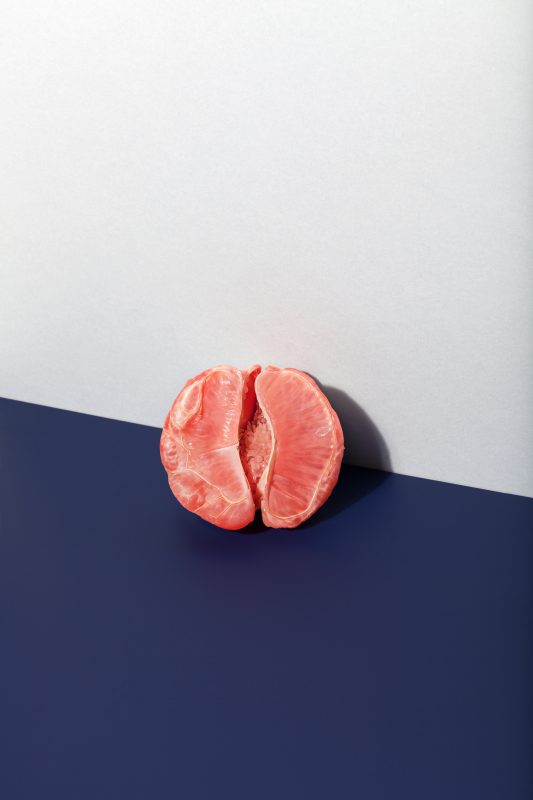

One of THINX’s provocative subway advertisements. Photo Credit: THINX

In the fall of 2015, Agrawal’s company submitted an ad campaign to run in the New York City Subway. The imagery: in one ad, a peeled half of a pink grapefruit. In another, an egg, just cracked open, dripping off a countertop. The slogan: “Underwear for women with periods.” The company that approves subway advertising was not so taken with the THINX ads. Among other things, they said the imagery was “inappropriate.”

AGRAWAL: I mean, the fact that the New York City subway system did not want to put our ads in the subway because of the word “period” shows that we are wrapped in this patriarchal system right here in the most progressive city in the world, New York City.

Agrawal took to the internet to stir up some feminist fury; eventually, the company did approve the ads.

AGRAWAL: I think periods have been used in a very political way for so long, to keep women down. If you look at the Bible, the Torah, the Koran, they all talk about if you touch a woman on her period you will be defiled. You — she’s considered impure and unclean. I mean, these are all tactics to keep women as second-class citizens. And it’s absurd because, we are the things that are the vessels in which men and women are created. I mean, I have a little mini male parts growing inside of me right now, and, a little boy, and that boy would not exist without that period blood. And the fact that it’s considered shameful and unclean and impure and you’ll be defiled if you touch a woman on her period… That’s clearly a tactic because it really should be a time of celebration and gratitude and appreciation for women and really lift them up and make them feel good during that that sacrifice every single month.

DUBNER: It just strikes me that some of the pieces that I’ve read about you by capital F feminists, they seem to feel that you’re not in the camp, in the feminism camp the way they want you to be. I don’t understand what they think you’re doing wrong. Is there something incompatible with commercial success and feminism for instance, or is that entrepreneurial-ism? Is it a weird form of misogyny that they’re exercising? I’m just curious to know what that is.

AGRAWAL: Yeah, it’s a fake feminism. It’s like people who wear the feminist sweater loud and proud and they’re actually not real feminists. They just pretend to be or they want to be part of a club, like you want to wear the cross around your neck and be part of church. You know what I mean? And the minute that someone doesn’t espouse the same God that you espouse in exact same way that you pray to that God then they will be judging you. I have zero tolerance for that. And I will come back with full integrity with what I believe to be real and true. I think about feminism through innovation and I think about it by offering products and inventing things that support women and make them feel less shame about themselves. But I don’t necessarily wear the badge loudly and proudly. And I do — I am a feminist. But I don’t have to wear that “Feminist AF” sweater to be a feminist. You know what I mean?

There is a substantial literature in economics showing that menstruation imposes a large cost on girls and women around the world. In some places, female students miss school or drop out entirely once they begin menstruating. Female employees who miss work because of their periods are obviously at a disadvantage. Low-income women and girls especially stand to gain a lot by addressing this problem. THINX’s panties, however, aren’t cheap – at least if you’re thinking only about up-front costs. They’re about $24 a pair.

AGRAWAL: And you can spend up to almost $200 for a seven-day cycle set.

But, Agrawal argues, that’s an investment that quickly pays off.

AGRAWAL: Your tampons are costing you about $12, including your, plus your panty liners, plus the dry cleaning for your underwear plus the ruined clothes. All that adds up.

So by her mathematical reckoning, with THINX period panties…

AGRAWAL: Within three months you’re totally paid up for the whole year.

She also promotes the environmental upside of clothing that gets reworn versus menstrual products that get thrown away.

AGRAWAL: Twenty billion plastic tampon applicators, pads, and menstrual products end up in a landfill every single year.

Now, we should say that environmental math is often a bit trickier than that. Just think about any of the reusable versus disposable products you’re heard about – cloth diapers versus plastic; a ceramic coffee mug versus a paper or plastic cup. Most claims that advocate for the reusable items don’t factor in their environmental costs – especially the laundering costs. All the energy it takes to heat the hot water for the dishwasher or washing machine; the water itself, gallon upon gallon of it; a runoff channel for the dirty, soapy water. So when you examine what’s called a life-cycle energy assessment for reusable versus disposable, it’s often not at all clear that disposable is worse, or at least much worse. We asked Agrawal about this argument; she didn’t show much interest:

AGRAWAL: I mean, when you wear a pair of underwear that lasts you two years, versus the, you know, you’re going through an average of 15, 20 tampons a cycle times a year, that’s 20 times 12, that’s 240 tampon applicators end up in a landfill. That’s way more than a pair of underwear by a country mile.

In any case – Agrawal sees herself as a disruptor of a practice, and an industry, long in need of disruption. And one disruption led to another.

AGRAWAL: The three Ps: periods, pee, and poop.

Next came pee.

AGRAWAL: People kept asking us, “Can we use this product for more than just periods?” For light bladder leakage. And so we developed Icon as a sister brand to THINX, which is our pee-proof underwear. And the idea is is that it offers a very simple solution for women who have light bladder leakage or stress urinary incontinence. Right now it’s a $6.9 billion incontinence category where Depends and Poise, these diaper products exist, which make women feel like shit. I mean, you pop out two babies and you might have a little bit of bladder issues and now you’re considered ashamed again by that, by perpetuating the human species? It’s just absurd. We developed a very simple product that has completely different technology to THINX. It’s specifically made for urine, for light bladder leakage. We have our first product holds 25 milliliters of urine. We’re doing a 50 to 75 milliliter hold next. They’re odorless, they’re fast-drying, they’re moisture-wicking, they are leak-proof, they have leak-proof seams, they’re seamless. We believe that Icon in itself could be a billion dollar business.

And then there’s the third component of Agrawal’s taboo triumvirate. It’s a product called TUSHY…

AGRAWAL: Which is a simple bidet product. Our bidet attachment is $69. It attaches to any standard American toilet, turns any toilet into a bidet in less than 10 minutes without any electrical or plumbing and it literally is the most transformational thing you can put in your bathroom. Why is our butts the only part of our body we clean with paper? If a bird poops in your face would you take a piece of paper and wipe it with paper or would you wash it?

Again, the impetus for TUSHY came from Agrawal’s own brand of feminist thinking:

AGRAWAL: Which is again out of a need because women were like, “How do I keep my vagina clean, how do I keep myself clean during my periods?” Especially when you get UTIs and hemorrhoids and things like that. When you think about the way we go to the bathroom and poop, that literally hasn’t changed since 1890. We were like, “No, this is ridiculous. How is toilet paper that was invented 1890 still the thing that we use to wipe our asses? Why don’t we know that it doesn’t really work?” Not to mention it’s completely unsustainable, it hurts sewage systems between toilet paper, wet wipe blockages. It’s astronomically terrible.

DUBNER: Why do you think Americans have been so anti-bidet?

AGRAWAL: Because English hate the French and the French invented the bidet. a Frenchmen invented the bidet, number one. I’m serious. And number two. Number two it’s because during World War II when Americans went to Europe to fight World War II. The American soldiers would go to French brothels, and they would see bidets in French brothels and then they associated bidets with French brothels. And when they came back they were like, “We weren’t in brothels. Ew. Gross. We think that’s terrible.” Meanwhile, they were associating, so they were like,“Oh it’s dirty.” They created this thing that bidets are dirty. Meanwhile it’s actually a thousand times cleaner than using paper and literally smearing poop up your butt and sitting on fecal matter all day long. That’s literally what you’re doing. And it’s been cost-prohibitive to get all these, like, very expensive Japanese toilets. People live in rentals, they don’t want to spend — our product is $69. You can check it out at HelloTUSHY.com. Do not go to TUSHY.com. It is a porn site. And that cookie will follow you around for a long time.

DUBNER: I want to ask you a series of lightning round freak-quently asked questions.

AGRAWAL: Sure.

DUBNER: If you had a time machine, when would you travel to — it can go forward or backwards — and why and what would you do there?

AGRAWAL: I would probably go back to the agricultural revolution when men went from hunting and gathering to becoming sedentary farmers. At which point, when they’re sedentary they started to want more power, because they spent all their energy and testosterone in the field trying to get food. And now food is growing no problem and so they want to now regain power from, because the women back in the day were actually the ones passing down wisdom from generation to generation. It used to be a matrilineal era when the women’s namesake was being passed down instead of the man’s namesake. But then it all changed. I would probably go back the agricultural revolution and really understand when that switch happened. I’d be just curious to see where it went from women being the dominant wisdom voice to the men and understand what can be done there.

DUBNER: That’s such an interesting answer. What’s one thing you’ve spent too much money on but don’t regret?

AGRAWAL: I think travel. I go on like two trips a year and it’s just the best, best money I’ll ever spend is traveling. Yeah.

DUBNER: What’s one thing you own that you probably should throw away but never will?

AGRAWAL: My Cornell soccer jacket. My boyfriend, my partner keeps saying like can we throw — we just moved — and he’s like, “Can we like…” And I’m like, “Absolutely not.”

DUBNER: What is something that you believed to be true for a long time ‘til you found out that you were wrong?

AGRAWAL: Ooh, that’s a really good one. That, I mean I didn’t realize that there were a billion obese people in addition to a billion hungry people on the planet and that was a crazy alarming thing to find out and know.

DUBNER: That is a mind-blower isn’t it? I mean, for all of human civilization we had one problem and then it in a blink of an eye really is the opposite problem. All right. And what is the best possible future discovery or invention?

AGRAWAL: Future discovery or invention?

DUBNER: The best possible, however you want to define that. Maybe it’s for what you think is the best or maybe it’s something that benefits humankind most of all, whatever it is.

AGRAWAL: I think it’s a vacuum cleaner for polluted air. I think like being able to create a thing that can just like swallow up all this air pollution and turn it into clean-air oxygen.

That was serial entrepreneur Miki Agrawal, running toward the taboos everyone else is running away from. Next time on Freakonomics Radio: Chuck E. Cheese is famous as a gathering place for families with kids. It’s also in famous as a place where fights break out.

VOICE: No! Chuck E. Cheese action.

What’s going on when a fight breaks out at a family restaurant — is it a pizza problem? An alcohol problem? Or, here’s another theory… a pricing problem? That’s next time, on Freakonomics Radio.

* * *

Freakonomics Radio is produced by WNYC Studios and Dubner Productions. Today’s episode was produced by Shelley Lewis. Our staff also includes Christopher Werth, Merritt Jacob,Greg Rosalsky, Stephanie Tam, Eliza Lambert, Alison Hockenberry, Emma Morgenstern, Harry Huggins, and Brian Gutierrez. You can subscribe to this podcast on iTunes, Stitcher or wherever else you get your podcasts. You can also find us on Twitter and Facebook.

Sources

- Miki Agrawal, entrepreneur and co-founder of THINX, Icon, TUSHY, and WILD

Resources

Extras

- The Incredible World of Period Underwear Patents by Rose Eveleth

- Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation by Elissa Stein and Susan Kim

Comments