I’ve written on the woeful state of Americans’ financial literacy a few times in the past. There is probably no academic researcher more attuned to the problem than Annamaria Lusardi of Dartmouth. This week’s NBER e-mail blast describing the latest crop of economics working papers includes nine papers; of those, four are written or co-written by Lusardi on this topic.

Among the highlights (or, I should say, lowlights); the bolding is mine:

“Americans’ Financial Capability”

This paper examines Americans’ financial capability, using data from a new survey. Financial capability is measured in terms of how well people make ends meet, plan ahead, choose and manage financial products, and possess the skills and knowledge to make financial decisions. The findings reported in this work paint a troubling picture of the state of financial capability in the United States.

The majority of Americans do not plan for predictable events such as retirement or children’s college education. Most importantly, people do not make provisions for unexpected events and emergencies, leaving themselves and the economy exposed to shocks.

The podcast we put out a few months ago called “The Power of Poop” continues to draw incredulous e-mails. In a nutshell: throughout civilization, human feces has posed considerable health hazards; when it gets into the water supply, for instance, a lot of bad things can happen. But in recent years, a variety of medical researchers, many of them gastroenterologists, have pushed for a greater understanding of poop, and have made some startling discoveries. Among them: fecal transplants (yes, you read that right) seem to provide substantial medical benefit for several maladies.

So it’s always nice to see fecal transplants in the news, as in this report from Tampa about a woman who was suffering from Clostridium difficile and had her health apparently restored by a “transpoosion” (although the method of the transplant in this case was, I have to say, much harder to stomach than the transplants we covered in the podcast — so you might not want to open the link if you’re eating …).

This statistic seems unbelievable to me on a few dimensions, but it is still worth thinking about:

The National Association of Homebuilders predicts that by 2015, 60% of new homes will be designed with “dual master bedrooms.”

From a CNN.com article called “Options for Your Mediocre Marriage.” One option:

If it’s possible, consider separate bedrooms. You’d be surprised how the creation of privacy and nonmarital spaces in a marriage might help. Already one in four Americans sleep in separate bedrooms or beds from their spouses.

Even if the 1 in 4 number is true (and that includes separate beds, not only bedrooms), I wonder how that translates into demand for a 60% supply of “dual masters.”

On Thurs., June 9, we’ll bring Freakonomics Radio alive (or die trying) on the stage of the historic Fitzgerald Theater in St. Paul, Minn. Details here and here.

St. Paul is home to our distribution/production partner American Public Media (the folks responsible for Marketplace, A Prairie Home Companion, etc.). It is also the hometown of Steve Levitt.

We have a variety of stunts and surprises in store (including some for Levitt: shhh!).

And we’ll preview some of the material from our five upcoming hour-long Freakonomics Radio specials airing this summer on public radio. The titles: “The Church of ‘Scionology,'” “An Economist’s Guide to Parenting,” “The Folly of Prediction,” “The Suicide Paradox,” and “The Upside of Quitting.”

If you live within reasonable distance of St. Paul, I very much hope you’ll come out; there’ll be a Q&A, book signing, and other yuks.

A good idea from a reader named Mark Mize:

Reading this article, I was immediately reminded of the section in SuperFreakonomics regarding altruism:

I think the choice to recline one’s airplane seat is a great example of natural altruistic tendencies. Reclining one’s own seat increases his comfort, but only at the expense of the person directly behind him. Then, in order for that person behind to increase his own comfort level back to what it was before the person in front reclined back into his space, he must now recline back into the space of the person behind him at the expense of that person’s comfort, and so on. An experiment observing this behavior may be a better measuring stick of natural human altruism tendencies than the Dictator game or similar games since the behavior could be observed in real time and without the behaviors associated with knowing one is being observed in a laboratory.

Interesting browsing these days on the prediction market InTrade, which is still mourning the loss of its founder John Delaney (a man I very much enjoyed knowing a bit the past few years):

1. Barack Obama to be re-elected President in 2012: 62.0% chance

2. Mitt Romney to be Republican Presidential Nominee in 2012: 29.6%

3. Sarah Palin to formally announce a run for President before midnight ET on 31 Dec 2011: 41.9%

4. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to no longer be President of Iran before midnight ET 31 Dec 2011: 31.0%

5. Dominique Strauss-Kahn to be guilty of at least one charge: 84.0%

6. Christine Lagarde to be named the next Managing Director of the IMF: 85.0%

7. The U.S. Economy will go into Recession during 2012: 20.0%

We should assume that Nos. 1 and 7 are inversely correlated. I went to the site this morning looking to see if there’s a contract out on Lloyd Blankfein, having read this (NYT) article, but I don’t see one (yet?).

Season 1, Episode 1

About one-third of the companies in the Fortune 500 are family-controlled firms. Isn’t that amazing? Isn’t that fantastic?

You know the story. Some incredibly hard-working person starts a business – maybe a bakery or a brewery, a carmaker or a newspaper – and, against all odds, the business doesn’t just succeed; it flourishes. But someday, it’s inevitable that the founder will retire (or die). So who takes over then?

That’s easy: the founder’s son or daughter. The scion of the family. Who better to protect and grow the family brand?

Makes sense, doesn’t it? Who could possibly work harder than someone whose name is on the building?

The family firm is a way of life. And it’s a nice story. But we’ve got a big, hungry economy here, people. “Nice” doesn’t necessarily generate jobs; “nice” doesn’t increase productivity or spur innovation. So when it comes to putting the family scion in charge of a company, here’s what we wanted to know: what do the numbers say?

We just got word that the new paperback edition of SuperFreakonomics will land on the 6/12 New York Times best-seller list. Freakonomics is still on the list too (88 weeks on paperback list after >100 on hardcover), and it’ll be fun to see if baby brother can hang in as long as the original. Thanks to all for reading!

Iced tea and lemonade are hardly perfect complements — they can each be happily consumed individually — but more and more I see them being served together. I have always known this combo as an “Arnold Palmer”; increasingly, however, as in this ad at the New York chain drugstore Duane Reade, it is known simply as “half-iced tea, half-lemonade.”

I like an Arnold Palmer just fine, but to my taste the best combo drink of all time is a cranberry juice and Fresca. What? You’ve never tried it?! Thank me later.

This has gotten me thinking about other wonderful complements in life. Surely many of them are in the realm of food and drink. But there’s also driving a convertible in cold weather with the heat on, e.g.

What are some of your favorite — especially underappreciated — complements? Tell us in the comments section and we’ll take five of the best and vote for the favorite. Winner gets a free copy of new SuperFreakonomics paperback.

Who is likelier to get to the fugitive first? When a fugitive is on the run, it’s not only the police he has to worry about. A bounty hunter could be coming after him, too.

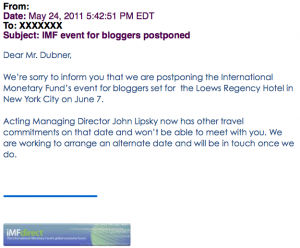

The Dominique Strauss-Kahn affair has been good business for many journalists and writers, but it’s caused some blowback too. Consider this IMF bloggers’ event that bit the dust:

And then there’s the admiring DSK cover story in Washingtonian magazine, called “The Invisible Man.” From the Washington Examiner:

“It was actually sitting at the printer, printed, when he was arrested,” explained the publication’s editor, Garrett Graff. … “The most ironic part of this is that the reason we were writing the piece is that nobody had ever heard of this guy,” Graff said. “You could be standing next to him at the supermarket check-out line and not recognize him.”

Yesterday, we ran a contest to give away five copies of the new paperback edition of SuperFreakonomics (which can be bought on Amazon and elsewhere). There were more than 640 entries! Thanks for all the support, and for betraying your thirst for free stuff.

So let’s have another contest right now. Last week, when we asked the best way to give away books, your second preference was “really hard contests on blog.” Okay then. But instead of having a quiz here on the blog, we’ve put it on our new Facebook page. So go ahead and “like” our page (if indeed you like it), and try your hand at the quiz. We’ll send a free SuperFreakonomics paperback to the first five people who receive perfect scores. (The tricky part is that you’ll do much better on the quiz if you’ve read the book but hey, the world’s not perfect is it?) Good luck!

It’s funny — when we ran a quorum recently asking what should be done about insider trading, no one mentioned cracking down on Congress. Maybe they should have?

A new working paper from Feng Chi, an economics PhD. student at the University of Toronto, is called “Insider Trading on K-Street: Are Politicians Informed Traders?” Here’s the abstract:

I investigate whether politicians take advantage of their privileged information that comes with their positions in power. Analyzing the trading records of Congressional members, I find that informed trades beat the market by 8.2%. As these gains accrue over the short term, my findings are suggestive of informed trading based on time-sensitive information.

And a couple of choice paragraphs:

Despite the potential for exploitation, Congressional members are generally free to invest in companies they help oversee. In addition, existing insider-trading laws do not apply to lawmakers. Probably to no one’s surprise, proposed bills to eliminate insider trading among Congressional members garnered little support on Capitol Hill.

Yesterday, the paperback edition of SuperFreakonomics was published in the U.S. (only $10.54 at Amazon!). And we used a random-ish contest to give away five copies. If I had known there would be so many respondents — more than 600 as of this writing — I would have had the winning comments correspond to higher values! Anyway: thanks to all for playing, and congratulations to the winners, who are:

Michael Mehrotra: comment No. 9, which corresponds to the episode number of our “Power of Poop” podcast.

Paulius Ambrazevicius: comment No. 10, which corresponds to our publisher’s street address.

Wade P.: comment No. 22, which corresponds to Hungary’s suicide rate (per 100,000).

“Power Pooper” (do we sense a theme here?): comment No. 32, which corresponds to the jersey number of my favorite football player, Franco Harris.

Pat Long: comment No. 43, which corresponds to Steve Levitt‘s age (at least for another few days).

Note: we counted the order of original comments, not replies, so as not to skew results.

Also: this was fun. We should do it again sometime soon, yeah?

The paperback is published in the U.S. today. Here’s what the cover looks like.

You can buy it on Amazon (and elsewhere).

There is a Facebook quiz forthcoming.

It includes lots of bonus material.

And just for kicks, we’ll give away five copies right here and now. Earlier, we asked your preferred method of giveaway and your strong preference was “random.” So why don’t we do things the way radio stations used to give away free records (maybe they still do this?) — you know, “The 28th caller will receive …” All you have to do is post a comment below. We’ll pick five comments from the lot, including the numbers represented by:

1. Steve Levitt’s age

2. Our publisher’s street address

3. The uniform number of my all-time favorite football player

4. The suicide rate (per 100,000) in Hungary

5. The episode number of our “Power of Poop” podcast

Good luck!

SuperFreakonomics comes out in paperback in the U.S. tomorrow. It includes a 16-page color insert with material from the Illustrated Edition of the book. Here’s an example, detailing the clever experimental variations the economist John List worked through on the Dictator Game:

(Click through to see a bigger version)

From a reader named Dmitry Mazin:

So I’m doing legalizing the organ market (selling your own organs only) for my speech class because I wanted to do something really repugnant and controversial.

Well, I passed out a survey to my class of about thirty people and two whole people were against this system. And this isn’t a progressive area — it’s in the Bible Belt of Southern California. Even Catholics were for it.

I think this corroborates that repugnance survey in the Freakonomics Radio episode “You Say Repugnant, I Say … Let’s Do It!”

So there you go.

Have a great day!

Hey, you have a great day too, Dmitry.

P.S.: I didn’t know there was a “Bible Belt of Southern California.” (Here’s a rare web cite about it; and here’s an earlier post called “We Pretend We Are Christians.”

In response to our call for blegs, a reader named Lisa Klink writes to ask your advice:

I just started a job at the Red Cross teaching preparedness education. The tough part is convincing people to take action: make an emergency kit, have an evacuation plan, etc. My question for your readers is: You already know that you should be prepared in case of disaster. What would prompt you to actually do it?

Great question. And not so easy. People like me spend a lot of time telling people like you that so many “disasters” they worry about are extremely unlikely. On the other hand:

That said, you’re reading the words of a guy who lives in New York City, and who lived here during the 9/11 attack, and has two fairly young children, and still never thought it worthwhile to load up a “go bag” with Cipro and cash.

It seems so coincidental that I wonder if indeed it’s a coincidence: the FBI requests a DNA sample from Ted Kaczynski, a.k.a. Unabomber, just as the government’s court-ordered auction of Kaczynski’s possessions gets underway (it closes on June 2). The FBI is still trying to solve the 1982 Tylenol poisonings, and Kaczynski is presumably a person of interest.

If nothing else, the news has brought a lot more attention to the auction. It can use it. As of this writing, most of the 58 items could be had for a few hundred dollars. Exceptions are Kaczynski’s Smith-Corona typewriter ($8,025) and his hand-written Manifesto ($16,025).

A reader named Mark Curry, who describes himself as a “cement truck driver trapped in the body of someone who does accounting-related work,” wrote to us about a brief passage in Freakonomics concerning our analysis of online-dating data:

The part about men with curly and/or red hair being a downer? “Downer” may be something of an understatement. As a young man I had red, curly, and sometimes, frizzy hair. My dad told me at age 13 or 14 that if I didn’t do something with it, I would never find out what sex is. I was devastated by his meanness. I consider myself very lucky to have found a woman who will tolerate my red hair. Now, married almost 18 years, a couple months ago I started shaving my head smooth, baby-ass, bald; does it feel good. Now, when I walk into an office, the bank, pick someplace, I don’t exactly have to ask people to stop undressing, but their receptiveness to me is noticeable. Although my wife and daughters are still getting used to my shaven head, at least a dozen ladies (that’s 10 women and two men) think my shaven head looks good on me.

I wonder if Telly Savalas was a redhead?

Last time I was in London I had a headache, and went to the nearest Boots to buy something for it.

In U.S. drugstores, I’m accustomed to finding half an aisle devoted to headache pills, with bottles ranging from small to very large — at least 200 pills in them. So that’s what I went looking for in Boots, but no such bottle was to be found. The only options were cardboard packets containing maybe 20 pills, with each pill in its own blister packet. (The pills were also larger than U.S. pills.) Hmm, I thought. I guess Boots finds it can charge a lot for a small amount of headache medicine since most people, when they have a headache, aren’t very price-conscious.

But I recently learned the real reason for this phenomenon while interviewing David Lester, a psychologist at the Richard Stockton College of New Jersey who is the dean of suicide (and death) research. (We are producing an hour-long Freakonomics Radio special on suicide.) We were discussing the efficacy of SSRI’s on treating depression (and fighting suicide) when he explained why it’s hard to find a big bottle of headache pills in England:

The subtitle is Choosing Boys Over Girls, and the Consequences of a World Full of Men. The book is forthcoming, and the author is Mara Hvistendahl, who was a very good research assistant of mine some years back. Mara transcribed many hours of interview tape with an economist named Steve Levitt for a profile I was writing. She has become an excellent reporter and writer; here’s my blurb:

“Yes, it’s a rigorous exploration of the world’s ‘missing women,’ but it’s more than that, too: an extraordinarily vivid look at the implications of the problem. Hvistendahl writes beautifully, with an eye for detail but also the big picture. She has a fierce intelligence but, more important, a fierce intellectual independence; she writes with a hard edge but no venom — rather, a cool and hard passion.”

Perhaps not where you think. A new Centers for Disease Control report is out: “Violence-Related Firearm Deaths Among Residents of Metropolitan Areas and Cities — United States, 2006-2007.” Notable patterns by geographic region were observed. All-ages firearm homicide rates generally were higher for MSAs in the Midwest (seven of 10 above the median MSA rate of 5.4 [per 100,000 inhabitants]) . . .

Here is another guest post on failure from author and Financial Times columnist Tim Harford, from his new book Adapt: Why Success Always Starts with Failure. In his first post, Harford wrote about why failure is often the mark of a healthy economy. Here, Harford writes about the process by which the U.S. military slowly learned from its early failures in the Iraq War. Hint: good ideas often come from the bottom and work their way up the chain of command.

Lessons in Adaptation: Winning the War in Iraq

By Tim Harford

In the spring of 1980, President Jimmy Carter gave the go-ahead for a daring special-operations mission called Eagle Claw. Fifty-two American hostages had been trapped for months in Tehran under a newly hostile revolutionary government, and negotiations appeared to have broken down. The operation called for helicopters and refueling aircraft to fly into the Iranian desert at night, under the radar screen, rendezvous in the middle of nowhere, refuel, and hide during the daylight hours.

From a Wall Street Journal article about Raj Rajaratnam‘s failed insider-trading defense strategy:

Mr. Rajaratnam is estimated to have paid as much as $40 million for his defense, according to people familiar with the matter and some lawyers not affiliated with the case, about two-thirds of the amount prosecutors said Galleon made from the insider trading addressed in the charges.

I bet I could have gotten him convicted on all 14 counts for $5 million, and I’m not even a lawyer.

What’s it like to wake up one day and realize Dad is a multi-billionaire? That’s what happened to Warren Buffett’s son, Peter — who then started to think about whether or not to join the family.

A reader named Patrick Nash needs your advice:

My friend and I have developed a cutting-edge technology for social media. There are other similar technologies out there for social media but we could never compete with their resources. Should we just point blank say we are the cheap alternative as a selling strategy? Sounds cheesy and flimsy but may be our only avenue.

What do you have to say to him? I don’t expect a lot of you to have experience specific to his product, but I know there are a lot of starter-uppers among our readership (yes, both kinds of starter-uppers), as well as what you might call “psychology of pricing” pros. So let’s see what kind of advice you have for Patrick.

The Times reports on New York City kids who fail to get into any of the high schools they apply to. Al Roth, who helped design the school-choice program but has no hand in running it, reports on why this failure occurs. (One big problem, from the Times article: a school like Baruch College Campus H.S. received 7,606 applications for 120 seats, many of them coming from outside of Manhattan; but the school “has not accepted out-of-district students in many years, a fact not mentioned in the Education Department’s school profile.”

Roth’s advice:

For students: use all 12 choices. The system is designed so listing 12 choices won’t hurt your chance of getting one of your top ones. But if you don’t get one of your top choices, having some other schools on your list that you wouldn’t mind going to will save you some heartache.

For schools and guidance counselors: give these kids more useful advice! They should be told if the lists they are submitting include only schools for which they have little or no chance of being accepted.

… with a very good column, including these useful words:

Positive economics attempts to understand the world as it is; normative economics describes how the world should be. Most economists spend most of their time doing positive economics, but most economics columns advocate particular policies, which is implicitly normative economics.

It’s a good bookend to Greg Mankiw‘s column from a couple days ago.

I’ve known Tim Harford for a while; to me, he’s one of the best writers who also happens to be an economist (although in recent years he’s spent more time as a writer than a practicing economist, which may explain everything). Disclosure: Harford profiled Steve Levitt back when Freakonomics came out, and he’s had the two of us on his BBC radio show More or Less.

He writes a Financial Times column (on Saturdays) called “Undercover Economist,” and that was the title of his first book, published in 2005 (and just updated). His latest book, out this week, is called Adapt: Why Success Always Starts with Failure. It examines the incremental, adaptive ways by which success is achieved across a number of fields. Here’s a taste, in the form of a guest post. It’s very good, and to my mind, here’s the best passage:

[W]here’s the churn in education policy or healthcare policy or policing? These are difficult problems. Why would we expect them to be solved the first time? They are surely no simpler than the business problems which seem so prone to experiment and error.

You want to listen to Freakonomics Radio? That’s great! Most people use a podcast app on their smartphone. It’s free (with the purchase of a phone, of course). Looking for more guidance? We’ve got you covered.

Stay up-to-date on all our shows. We promise no spam.